Carlo McCormack in collaboration with Wooster Collective’s Marc and Sara Schiller, Trespass; A history of uncommissioned public art (Cologne: Taschen, 2010) ISBN978-3-8365-0964-0

Urban Interventions; Personal projects in public spaces, Robert Klanten and Matthias Hübner, eds. (Berlin: Gestalten Verlag, 2010) ISBN 978-3-89955-291-1

Both of these large, profusely-illustrated books address the same general phenomenon: artists’ uninvited interventions in the urban environment.

One book illustrates projects by more than 150 artists or collectives, the other more than 120 and only 27 are covered in both volumes. Together they record a broad phenomenon, including artists primarily from Western Europe and the U.S., but also Australia, Canada, Brazil, Russia and Eastern Europe, and the very occasional work sited in Africa and Asia.

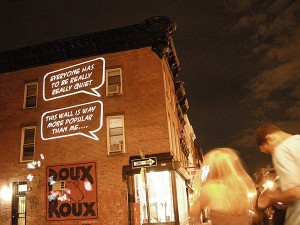

Tresspass addresses a longer period, with work as early as the 1970s, and includes a number of artists who have exhibited internationally in galleries and museums, in addition to working in the streets. These include Gordon Matta Clark (whose photograph of broken windows in an abandoned property graces the dust jacket), Vito Acconci, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Group Material, David Hammons, Keith Haring, Jenny Holzer, Tehching Hsieh, Barbara Kruger, Charles Sim monds, and Krzysztof Wodiczko. Some of the inclusions reflect a rather broad idea of uncommissioned urban art, including actions and performances such as Acconci’s Following Piece or Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performance 1981- 82, Outdoor Piece that, while executed in city streets, probably had no audiences there, and only reached a public later via documentation exhibited in galleries and museums.

Short essays by several writers situate this work as inherently political. According to McCormick, a critic who documented the East Village art scene as it evolved: …the uncommissioned intervention is a reflex against the hegemony of public space by the interests of the few over the psychological well-being of the many. In a brief foreword, Banksy states: graffiti is the sight of an unregulated free market getting the kind of art it deserves. An appendix by lawyer, J. Tony Serra, discusses the legal situation of graffitti and attempts to distinguish graffiti, which he defines as art, from outright vandalism, a distinction U.S. law does not recognize.

McCormick does not attempt to fit such non-canonical work within the strictures of a linear history; instead he arranges it thematically under headings such as Public Memory/Private Secrets; Deviant Signs, Free Art, and Contra-Consumerism; and Environmental Reclamations. His introductions to the sections are light on real information and incomplete as analysis. There is minimal text for each work: the artist (or collective), date, location, and sometimes a credit for the published photograph. A few entries give materials, some have artist’s notes of no more than a sentence, and others have a line or two of commentary. I assume McCormick is trusting Google to direct readers to further information on anything of particular interest; and there’s a lot I’d like to know more about.

This is neither a history of the subject nor a reference work. It is most useful for the visual documentation (itself uneven) of a broad range of artwork that, by its nature, has been left out of most art world publications. The images are drawn from Wooster Collective, an organization which collects documentation of graffiti and ephemeral work, and many have not previously been published. It emphasizes work that is or grew out of the tradition of graffiti; while political in the sense that it is a reaction to disempowerment by marginalized groups, it often makes no obvious statement beyond recording the artist’s having been there, rather like dogs’ marking.

Some of the work, however, is clearly critical, others motivated by an overt generosity to residents of particularly blighted locations, and some seem driven by a whimsical humor. All three converge in Park(ing) Day (2005) by Rebar (above), in which a swath of grass, potted plants and seating were sited in a San Francisco parking space at midday to form a public amenity, until the meter ran out. Their initial venture inspired an annual event, held in more than 500 cities on six continents, that explores new ideas about public space. Just this week University City, in West Philadelphia announced a program based on Rebar’s initiative.

Urban Interventions is also arranged thematically, with fairly little overall discussion, but offers slightly more description (two or three lines) for many of the projects, all of which were produced since the turn of the millennium. In an opening essay, Lukas Feiriss says: … numerous projects illustrated in this book reflect upon a very basic observation within cityscapes, namely the silent subversion of its given forms, norms, and regulations. “Urban Interventions” upholds the tradition of how ordinary users and inhabitants of the city challenge and adapt civic spacial rules to their benefit.

Jason Eppink describes his work (below) as an ongoing series of public furniture installations aimed at increasing the availability of seating options in New York City subway stations…”Take a Seat” creates value simply by relocating an object to a new location. Rescued chairs—once liabilities—become assets with little to no effort. and encourages others to join him: How To Participate: Simple! If you see a chair in the trash, snag it, clean it up, and take it to your nearest subway station.

Klanten and Hübner favor projects that go beyond walls, and only a few situate themselves relative to graffiti, often by creatively integrating existing graffiti into a larger visual statement. They favor whimsey and humor; many of the artworks clearly give passers-by a reason to smile. They would generally be considered aesthetic improvements, even by that part of the community that rejects traditional graffiti as art. It turns out that some of them, while being urban interventions, were indeed sponsored, sometimes by art institutions (such as Nuage Vert, below, which was produced by the PixelAche festival of electronic art). The book does not always indicate whether the work was authorized or not; but I suspect a number of the artists will be approached by official groups for future work, since they are the sort of responses to the urban situation that cultural councils, transit systems, chambers of commerce and tourism bureaus like to support. The book’s index includes web addresses for all the artists rather than printing further information about them. That’s a help, at least, and it means the information will be updated, such as this project in Warsaw, below, by Luzinterruptus just last month:

…the installation finished by recycling itself in a spontaneous manner.

It would be good to read a serious analysis of unsanctioned art in public spaces that discussed the involvement the artists had with local communities, both before and after the works were installed. I would like to know about the longevity of those works that were constructed with weather-proof materials; did the communities assume ownership? Given the breadth of artwork covered in both books, it might not be productive to deal with it all together. The artists obviously had many different intentions and I’d say there were several different phenomena involved; but some thoughtful case studies would be useful.

Trespass brought up the notable youth of the artists; that certainly bears investigation. What happens when they age? Enough time has passed to begin such inquiry. We know that Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger have been embraced by the art establishment, and willingly so. But Krzysztof Wodiczko remains a thorn in the social conscience; I’m not certain he makes anything to sell. David Hammons has severely limited the institutions where he is willing to exhibit, and Suzanne Lacey (who is not covered in either book) is now able to get foundation funding, but continues to work on socially-committed urban projects.

More than a few schools offer MFAs in community arts, a term which describes at least some of this work. Some projects in Urban Interventions were done for a university workshop on urban art in Madrid, and the New York Times recently wrote about the phenomenon. What have been the implications of this work entering the academy?

Could one write a history of this art? Is its proliferation related to larger social or political circumstances? Information and imagery circulated on the web has certainly had some impact, but what, exactly? Gathering the material and providing documentation of works that were far-flung and often ephemeral is obviously a valuable start. But it is only the first step.