When Roberta paid a visit to Matthew Rose in Paris one afternoon in November, she learned from the artist and writer that in the early 1990s when he was living in New York and working as a freelancer, he wrote a magazine article for Vogue on the lives of studio assistants to Jasper Johns, David Salle and Sherrie Levine. Incredibly, the piece was never published despite the fact that the copy was ok’d for publication and the photos were taken. The story was squashed by the editor. Roberta told this interesting story to Libby, who, upon hearing it, said, “Tell him we’ll publish it on artblog!” A great idea, to which Matthew graciously agreed. He’s been in touch with the studio assistants to get some photos and updated information on what they’re currently up to. And here is the article, “Portrait of the Artist as a Young Assistant,” with a new coda at the end with 2007 information on the players. We are pleased to publish this art historical piece and will run it in several parts due to its magazine-length word count.–Roberta and Libby

Artists recall their initiation into the artworld of the 1980s.

In 1984, James Meyer was 22, living in Brooklyn and living off of hamburgers. The young artist was also something of an expert, painting copy after copy of Van Gogh expressionist and Matisse fauvist masterpieces. His client for all these sunflowers and dancing nudes was the meat and eat chain, Beefsteak Charlie’s. “I must have painted 300 of them,” he confessed. “For about $6 an hour.”

Meyer’s friends grew as tired of his moaning and offended by his hamburger outlook as he was. “Get a job with a real artist,” they told him. “It’s the fastest way to get into the art world.” Using his two years of art school, “few days in the navy,” and exhibition resume garnered from the then-emerging storefront East Village art scene, he was determined to make his mark even though, he said, “I didn’t know any real artists. My art education essentially stopped at the Impressionists or thereabouts.”

Meyer dug up a list of working artists, scribbled down their names and addresses, printed up a set of slides and resumes and, like a reluctant bible salesman, set out knocking on doors in artist-rich downtown Manhattan. On the top of his list was Pop legend Jasper Johns.

Knock twice

“I put on a suit, too, and went over to Johns’ Houston Street studio – this large old bank building – and tapped on the door,” he recalled. “Someone opened up, looked me over, took my resume and slides and unceremoniously said ‘Goodbye.'” It was unsettling and Meyer began to fidget. Three hours later he was back at Johns’ studio determined to collect his materials and get a real job, perhaps managing a Beefsteak Charlie’s! He knocked and waited. “Jasper opened the door and invited me in,” he remembered. “Would I like some coffee? We sat and talked and soon discussed money. Johns said, ‘Come back tomorrow and we’ll take it day by day.'”

Meyer’s first day on the job with Johns came with a terrifying realization: “Jasper hired someone with absolutely no knowledge of his business – paintings, prints and bronzes. It was insane.” Frightened of screwing up, Meyer said, “I stayed in the basement sweeping for about three weeks so I wouldn’t break anything.” In fact, he almost longed for his Beefsteak Charlie’s job. But the days flew by and finally the young assistant emerged with a growing understanding of who exactly Jasper Johns was in the art world. So, Meyer began to make himself more visible in the studio itself, and within a year showed his mettle, organizational skills and painting know-how. So much so that Meyer’s organization of Johns’ studio in lower Manhattan and then later at the brownstone studio in Gypsy Rose Lee’s old white home on East 63rd Street were soon minutely reproduced by the young assistant – at a studio in Upstate New York and on the Caribbean island of St. Maarten. All are identically equipped right down to the wax supplies, brush types and hot plates to cook up Johns’ special encaustic. “In St. Maarten, there’s no going out to Pearl Paint!”

The apprentice system

The history of art is often littered with the influence of one artist upon another. Nowhere is this influence more pronounced than in the master-apprentice system, a career strategy for young artists as viable in late 20th century Manhattan as it was in 15th century Florence. While perhaps a factor in the creation of cave paintings, the “system” was more or less formalized in the 500 years spanning the School of Rembrandt and Warhol’s factory. A mix of teacher-student relations, friendship, the addition of savoir-faire and technical expertise, the atelier and workshop and guild systems have spawned hundreds of successful artists from the studios of da Vinci, Dürer, Ingres, Manet and Mondrian to sculptors like Anthony Caro who heaved stone for artist Henry Moore.

While not exactly a genetic mechanism of art history, it’s probably as close as we get to the passing of the mantle to a younger generation. In return for stretching canvases, answering the phone and going for the mail, assistants get paid a decent wage, meet dealers, other painters and critics and find a place in the art community as well as drink (and sometimes eat) for free. For today’s artists the chance to learn not only technique and craft from a more experienced artist but also lessons about attitude, ambition as well as hype, money and media have become a critical, if not essential, set of lessons in the contemporary art world.

Beyond drudgery

Peter Bellamy

David Salle was perhaps the hottest of the 1980s artists then. His large semiotic canvases with prostrate women painted in grisaille and objects and words (like “Tennyson”) emblazoned on them, seemed the perfect response to the make-believe “morning in America” world fostered by Ronald Reagan. With a bevy of artists commanding million dollar bounties for their canvases, Salle’s world was one of a kind and there were more than a few starry-eyed artists willing to do whatever it took to get near this comet.

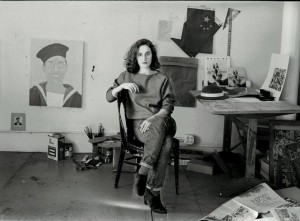

Annette Lemieux was one of the lucky ones. The then 23-year-old artist spent nearly half the 1980s working as David Salle’s all-round gopher and secretary, sometimes stretching canvases, sometimes scrounging about stores for objects. Salle was Lemieux’s teacher at the Hartford Art School (“I think he gave me an A.”), and it was just that time, in the early-1980s that Salle was getting splashed all over Vanity Fair for his brand of subversive metaphor.

Lemieux was there for all the accolades, and, more importantly, the creative action on the walls. “One day you walk in the studio and there would be a chair hanging off a painting,” she said. Lemieux, a conceptual artist whose penchant for mixing words, objects and photographs is much like Salle’s, certainly enjoyed a rich experience working in the studio, but it was strictly “employer-employee – 10 to 6.”

She added that there was no collaboration in Salle artworks. “David never called me over and asked what I thought about this red square,” she said. “There was no training, but there was the adventure of possibility unfolding every day.” While Salle served as a good model, she had always known how to work and how to edit her work. As for “the star,” she never found that David Salle who swirled and danced around the studio reveling in his genius. “The star was working.”

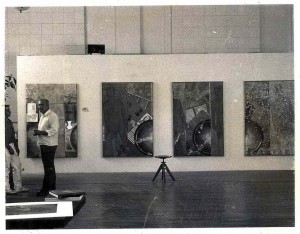

Choose 3 Artists,” exhibition at Artist Space, 1984.

But the star was also helpful, she added. While at home in Connecticut, recovering from being hit by a van (Lemieux had medical coverage through Salle), “the Salle” called to tell her he selected her for “3 Artists Choose 3 Artists,” a 1984 Artists Space show. (She exhibited “Manna”). It was a bold and generous move, putting Annette Lemieux on the art world map. She returned to work part time, but soon her career took off with shows at Cash/Newhouse Gallery, followed by favorable write-ups in the New York press. When Cash/Newhouse folded, Lemieux turned down several offers from well-known galleries to join up with Josh Baer, the art dealer son of Jo Baer. Lemieux’s inclusion in the 1987 Whitney Biennial seemed to top a dizzying decade of successes.

Lemieux’s production was so bountiful and her expressive directions so multifaceted that her first solo exhibition, she recalled jokingly, was labeled “a group show.”

She uses any number of surprising elements in her work from old doors and typewriters to hats, sheet music, antique furniture and stacks of books, and lots of photographs blown up and printed on canvas. Her conceptual works evoke the Depression, the great wars, the 1950s and the tentativeness and strength of the American family. Like Salle, Lemieux carefully selects and combines objects to reveal how various roles and ideas – mother, father, country, nostalgia, romanticism – are played out in American culture.

By 1990, Lemieux’s painting “Dirge,” a large canvas covered with funeral march sheet music hung next to Salle’s “The Silver” in the quasi-museum retrospective, The Last Decade: American Artists of the 80s at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery. “Success is very luxurious,” said Lemieux, obviously enjoying hers. “It allows you to have a studio, produce work as you like, and even have an assistant or two of your own.”

[Read more of this story in Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4.

[1/9/07, 7:55 p.m.: This post now contains two corrections of its original version. Lemieux emailed to say she was 23 at the time, not 33, and Manna was made in 1983, not ’84 as originally posted. Thanks, Annette].

Matthew Rose is an artist and writer living in Paris, France.