Robert A. Pruitt–the artist Robert Pruitt from Houston, TX, and not the inside-the-beltway artist Robert Pruitt from NYC–stopped by the Institute of Contemporary Art Thursday (Oct. 13, 2011) to talk about his art.

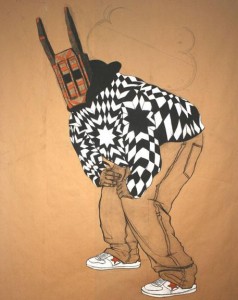

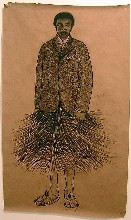

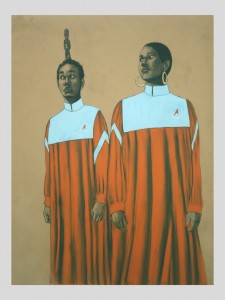

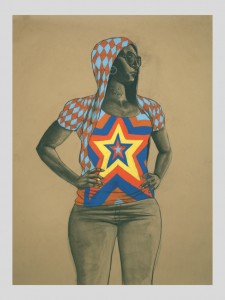

Pruitt’s 50-inch-ish conte crayon, charcoal and mixed media drawings on Kraft paper (and more recently paper dyed with tea) pair gorgeous drawing technique with ideas about contemporary culture, especially about fashion and race and identity. He has also made video, animations, sculptures and is part of Otabenga Jones and Associates, a collective of African-American artists with something to say about race in the art world and its institutions.

I saw Pruitt’s work in the 2006 Whitney Biennial, in 2005 at the Studio Museum in Harlem, and this year at the Fabric Workshop and Museum (he was in their New American Voices exhibit). His residency at the FWM plus a visiting artist gig at Penn are part of what brought him to the ICA here.

The audience on the night of his talk was filled with students, and some strays like myself (I’d guess more than 100 attended).

The first slide Pruitt flashed was of an Edward Curtis photo of a Navajo dressed in the costume of the water god. “It’s an alternative way of living and being. I’m interested in how that existed.”

He said his drawing technique grew out of his love for Marvel Comics and copying them, as a boy.

His work, mash-ups of exotic cultures, and of historical eras with today, reflects interests in how fashion expresses ideas about being human, and how those ideas vary in science fiction, pop culture, and other cultures past and present. For inspiration he spends a lot of time scouring the Internet with no set idea of what he’s looking for. That’s how he stumbled on the Native American dancer, and that’s what set him thinking of the oddity of Mr. T ‘s “post-’60s and -’70s bravado” with its relationship to hip-hop bling and African kings’ adornment (check out the original image of Mr. T with his animated bling).

Some things that set Pruitt wondering include the leopard skirt on a dark-skinned character from an alien planet in Star Trek, and singer-songwriter T-Pain in full regalia. Pruitt, on seeing T-Pain’s look, wondered, “How does he walk out of the house?” In the context of Pruitt’s drawings, these images, which we just accept as part of our culture’s visual landscape, look weird and wonderful, indeed–delivering a National Geographic sort of ethnographic fascination once you take them out of context.

Pruitt said he hopes to capture the way Sun Ra and Miriam Makeba each used Egyptian styles to grab their audiences’ imagination. “I’m looking for a place that’s outside to fit in.”

Eventually Pruitt veered away from his discussion of the drawings. “It’s troublesome for me to say too much about them.”

During his residency at the Fabric Workshop, he first made some drawings of some objects. “Drawings are the meat and potatoes of my process,” he said. Then he made the ideas into sculptures and photographs. For the photographs, he used different cameras from different eras. The things he made were bankrolled by the FWM. “It’s more fun when someone else in paying for the materials,” he joked, and said, “I’m still trying to see how I feel about these images.”

Lately he’s been making African sculptures covered with aluminum foil. “I really like them.”

Then he turned to living in Houston and Otabenga Jones and Associates. “Someone asked me, Why do I stay in Houston? It’s sort of the place I know. If I want to respond [to a culture and place], I need to know it.”

Ota Benga is the name of an African pygmy who was displayed at the Bronx Zoo. Besides Pruitt, the group includes Jamal Cyrus (who has a Penn MFA) as well as Dawolu Jabari Anderson, and Kenya Evans. Among the group’s activities were picketing a Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts show of a collection that was “limited in scope,” i.e. Euro-centric. It was Pruitt’s first ever demonstration, and he carried a sign that said, “My Blackness is Bigger Than Your White Box.” The group also curated an exhibit at the Menil Collection–selecting objects from the collection mixed with the artists’ own objects. “We tried to create an equalization of values.” Saturday teach-ins were a part of the exhibit. They were modeled after historic Black Panther education sessions.

He said he thought that the action at the MFAH and the show at Menil had some degree of impact on how the institutions deal with blackness in their exhibits.

His animations reflect his attraction to the militancy of Black Power proponents of the past–it’s “the same issues that oppress the black community now,” he said, and added that Obama and other contemporary powerful black men were not discussing those issues now. He was unhappy showing the animation at the scale of the auditorium screen. “My video doesn’t belong on a museum wall,” he said, preferring YouTube and the small screen. The sound track was from a speech by Amiri Baraka. The animation, he said, “can liberate that speech from the moment it was made.”

The Q&A that followed the talk was lively. Someone asked about the link between science fiction and history. Pruitt said he was interested in utopic space and “radical histories contemplating the struggle to get rid of structures like slavery.”

He said comics are a romantic way of seeing the world, and “for me, they are a way of re-imagining the human condition.”

Someone wanted to know about who he imagined was his audience. Although his work appeals to an art audience, Pruitt said he also wanted it to reach a black audience, and appeal to people of color in general. “How can I make drawings of great blackness?” he said, parallel to the way that art museums display images of great whiteness.

Then he returned to the subject of whether museums have a broad enough perspective. “Any project a museum brings us (Otabenga Jones), is suspect. The museum just has a different goal.” Then he said, “I am trying to do a couple of projects in which I give the work away, so people could, if they want a piece, take it away.”