Rivane Neuenschwander: A Day Like Any Other opened at the New Museum, New York in June, 2010 and I caught up with it at its final stop, the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA, on through January 29, 2012). Organized by the two museums, the exhibition was also seen in in St. Louis, Scottsdale and Miami. Neuenschwander is from the first generation of Brazilian artists to come to international attention early in their careers, but she inevitably stands on the shoulders of the Frente and Neo-Concret artists of the late 1950s-1960s (Helio Oticica, Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape and others). Some of her references may be lost in translation, but the work has enough energy, generosity and sensitivity to the world at large that it holds up well in alien environments. Neuenschwander deals with subjects of time, death, social responsibility and environmental awareness in a poetic manner that sometimes teeters on the edge of sentimentality, but falls in the right side.

The exhibition was held in the domestically-scaled rooms of the IMMA’S New Galleries, the area open during the renovation of the primary spaces in the Royal Military Hospital, Kilmainham. The initial room held At a Discrete Distance, a series of precisely-painted and rather cheerful landscapes which emphasized patterning of floor tiles, roof beams and stairs; they were painted on small panels which the label related to Brazilian devotional paintings, although they gave no clue to wished-for desires.

A room full of Involuntary Sculptures (Speech Acts) (2001-10) held vitrines full of of small, hand-made objects that Neuenschwander had found, abandoned, in various bars and restaurants. These small sculptures, three-dimensional doodles really, had been fashioned from corks, plastic straws, matches, toothpicks, paper napkins, chop-stick wrappers, pop-tops and champagne cork wires that had been twisted, folded, shredded, crimped and burnt. They were by-products of social activities whose excess energy had been channeled through manual activity. While they bore signs of varying degrees of craftsmanship and imagination, Neuenschwander’s interest was in their association with sociability, hence the second part of their title, Speech Acts. Intriguing as they were, it struck me that almost anything laid out carefully in vitrines comes to resemble art.

The protagonist of the video, The Tenant (2010) is a large soap bubble which meanders through the rooms of an empty house, and the conceit is so charming that it doesn’t matter how it was effected. I was willing to accept the agency of the wobbly sphere, always a moment away from bursting, that magically refracts light at its periphery. The wonder at soap bubbles does not diminish with age.

The widely-appealing, interactive installation, I Wish Your Wish (2003) is again based upon vernacular, devotional practice, where the faithful bind their wrists with ribbons which they then leave tied to the church gates. Neuenschwander’s adaptation had visitors leave a wish in exchange for a ribbon printed with a previous visitor’s desire, which ranged from the individual to the universal, the selfish to the profound: wishes for a dog, to get into grad school, for family’s understanding, for respect for native people’s sovereignty, peace in the Middle East, not to die completely alone. Participants were forced not only to declare their own wishes, but to choose among those offered by their predecessors, and while the process was something of an exercise in ethics, it was surprisingly effective. I left with my wrist wrapped in a turquoise ribbon inscribed I wish to find pleasure in things as much as I used to as a child; it struck me as particularly appropriate to Neuenschwander’s art.

A Thousand and One Possible Nights are collaged images of constellations, created from confetti punched from an edition of Scherehazade’s tales, A Thousand and One Nights. Images of the stars are always beautiful, as are these; the printing on the tiny dots only becomes visible at close range. Yet a second thought reminds us that Sherehazade told her stories to forestall death, something behind much art, perhaps, but the connection is rarely so literal and immediate.

I had hoped to get more context for Neuenschwander’s work in London, where the Serpentine Gallery is showing Lygia Pape: Magnetized Space, organized by the Reina Sophia (through Feb. 19, 2012). Pape’s two and three-dimensional work obviously derives formally from Constructivism, and some of it resembles Bauhaus pedagogical exercises. The large installation, ‘Ttéia 1 (The Web)’, whose illuminated wire shafts create an otherworldly atmosphere, looks like a stage set for a play about heavenly revelation.

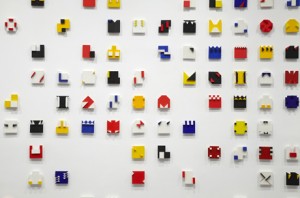

The 365 small wooden reliefs of Livro do Tempo (Book of Time), that covered a large wall, formed an irresistibly-fascinating grid of variations on a square; small sections had been excised from each and displaced on top of the original, with varying colors emphasizing the variations in forms. It and a room of black and white prints and drawings combined seductive elegance of both formal interest and execution. Yet the connection between this work and the interactive, communal performances for which she is known was unclear, nor did labels to several filmed performances provide much help. This was disappointing, since with many recent artists working communally and sociability an ongoing topic, the comparison should have been illuminating.

For understanding the social and political implications of working in a repressive state for Pape and her fellow Brazilians, it was very useful to read the recent publication: Subversive Practices; Art under Conditions of Political Repression: 60s-80s / South America / Europe, Edited by Hans D. Christ, Iris Dressler (Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern, 2010, ISBN 978-3-7757-2755-6 ). The catalog to an internationally-curated exhibition held in Stuttgart in 2009, it illustrates work by some 80 artists working in Latin America, Spain and Eastern Europe. Much of their surviving work consists of publications, documentary photographs and ephemera printed in connection with communal events, so reading the book might be almost as illuminating as seeing the exhibition.

The catalog is an extremely valuable complement to a number of recent publications addressing conceptual practices beyond the U.S. and Western Europe (such as Global Conceptualism; Points of Origin 1950s-1980s, the Queens Museum, 1999, and anthologies by Camnitzer, Albero and Stimpson, Breitwieser, Katzenstein and others). It includes essays by the editors and their 13 co-curators, and provides the first translations (into English and German) of numerous artists’ statements and manifestos. They give valuable context for a range of art practices and activities in public spaces that were inherent affronts to state power, despite seeming tame and unobjectionable in a Western European and North American context. Examples are Collective Actions Group’s Trips out of Town (above), which were nothing more than organized outings to the countryside, and the gathering organized by Edgardo Antonio Vigo in La Plata (Argentina) in 1968. Vigo advertised in the newspaper and on radio for people to meet at a specific time at a major intersection in the city; the object of their assembly: to contemplate the traffic light as an aesthetic object.