THE WHITNEY Biennial in New York claims to take the pulse of the country’s art scene every two years, but the mother of all American art exhibits rarely digs deeper than New York or Los Angeles. For the radical “People’s Biennial” now at Haverford College, curators looked elsewhere. The exhibit eschews work from major art centers in favor of five regional outposts (including Philadelphia) chosen through a jury process open to all. Organized by artist Harrell Fletcher of Portland, Ore., and curator Jens Hoffmann of San Francisco, People’s Biennial originated when the two brought their idea for a nontraditional biennial to Independent Curators International (ICI), a group that supports new types of curatorial practice. ICI embraced the idea, and Fletcher and Hoffmann were off and running.

The two scoured the country in search of interesting, provocative art by people – not necessarily artists – who are overlooked and marginalized. (Coincidentally, the Portland-based Fletcher, known for his collaborations with nonartists and for art that is not an actual object but more like a social happening, was himself in the 2004 Whitney Biennial.)

Haverford was one of the first venues to apply for the Biennial. ICI selected the college because it was eager to participate in the yearlong process of putting the show together. Haverford also provides student and suburban audiences, which reinforces the show’s outsider identity.

The 36 artists in the show include eight from this region and 28 from the other regions, including Portland; Rapid City, S.D.; Winston-Salem, N.C.; and Scottsdale, Ariz. People’s Biennial has traveled to each city over the last two years; Haverford is its last stop.

The Haverford opening on Jan. 29 was nontraditional. Portland artist Rudy Speerschneider gave out homemade cheesesteak-flavored ice cream. Local artist Maiza Hixson videotaped viewers, asking them what they thought about the show’s red, white and blue branding on its website, in the show catalog and in the wall text, which looks like the styling of Howard Zinn’s polemical 1980 book, A People’s History of the United States.

For local contributions to the show, Matthew Callinan, Haverford College’s campus exhibitions coordinator, and his student helper David Richardson were charged with finding local artists outside the circle of professional artists who make up most group exhibitions in the region. The two flooded the town’s coffee shops with postcards, met with staff at community centers to get names and ideas, and talked up the project with friends and anybody they met. They also made an online call for artists.

Fletcher reviewed work brought to two open calls, one at the Friends’ Center in Center City and one at Haverford; he also chose from work submitted online. About 70 people showed up for the two open calls. According to Callinan, they represented a diverse set of backgrounds and experiences: “Those who had never been in art school or never been in an art class, recovering drug addicts, but also Maiza Hixson, who has a graduate degree.”

Hixson is an artist and, post-open call, a curator at the Delaware Center for the Contemporary Arts in Wilmington. “I was No. 6,” she said about going to the open call, which was a take-a-number process. “I was told, ‘Harrell will be over to see you soon.’ I was really nervous. It was like being in an experiment.”

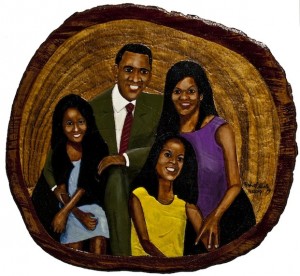

Hixson’s work is one of three documentary videos in the show, which seems like a lot of documentary videos in a show that’s otherwise filled with simpler works. And while there are no traditional artists in the show, the work represents the traditionally expansive range of art-making. The show features clay sculpture, piñatas, soap carvings, drawings, paintings, including one on a slice of tree trunk, and exquisite black-and-white photographs of rodeos and street scenes from Guatemala and Mexico.

In terms of quality, some of the art resembles that in a commercial gallery. Other work is sweetly innocent, made either by a child (a father submitted his daughter’s art, in one case) or by a mentally challenged individual. The most radical entry is a group of works that represent sentences meted out in Portland Community Court by a judge who allows offenders to “art” their way to atonement.

The show veers from outsider art to more sophisticated without skipping a beat. Here, everybody is in one big happy boat of a show. That’s the value of People’s Biennial. The work is charming, but what’s more noteworthy is the democratizing idea behind the show, which gave nonstandard artists a dignified national platform to exhibit works.

With an eye toward the future, “People’s Biennial” ends with a People’s Conference. The free two-day symposium on Feb. 24-25 will review what’s been accomplished and assess how the idea might be adopted by others. Speakers and moderators will include Fletcher, Hoffmann and ICI director Renaud Proch.

“People’s Biennial,” through March 2. Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery, Haverford College, 370 W. Lancaster Ave., Haverford,

This story ran in the Daily News on Feb 3, 2012 as part of Art Attack, a partnership with Drexel University supported by a grant from the Knight/NEA Community Arts Journalism Challenge and administered by the Greater Philadelphia Cultural Alliance.