Well, Roberta, you are a terrible trouble maker. After all, not that long ago (Oct. 5, to be exact), you wrote a rave about Jan Baltzell’s abstract paintings.

Of course, only people of a certain age are painting abstractions, these days. Walk into any hip young gallery and you’ve got cartoons, fashion statements, stuffed animals, natural objects in unnatural spaces, unnatural objects in natural spaces, etc. (Shown, “Wigs,” from Andrew Jeffrey Wright’s show at Spector.)

Of course, only people of a certain age are painting abstractions, these days. Walk into any hip young gallery and you’ve got cartoons, fashion statements, stuffed animals, natural objects in unnatural spaces, unnatural objects in natural spaces, etc. (Shown, “Wigs,” from Andrew Jeffrey Wright’s show at Spector.)The main trouble with abstraction is that most people don’t get it most of the time. And art lovers get it only some of the time.

For one thing, there’s a lot of dross out there. For another, you’ve got to be steeped in art to get abstraction (shown, Kandinsky’s Black Lines). It requires a viewer with time to ponder, who is familiar with painterly and rendering strategies, with some art history, and with a willingness to look at the brush strokes and past them (the brush strokes, after all, are not enough to hold the interest of your average bear or even your average art lover).

For one thing, there’s a lot of dross out there. For another, you’ve got to be steeped in art to get abstraction (shown, Kandinsky’s Black Lines). It requires a viewer with time to ponder, who is familiar with painterly and rendering strategies, with some art history, and with a willingness to look at the brush strokes and past them (the brush strokes, after all, are not enough to hold the interest of your average bear or even your average art lover).

The problem with a lot of abstract painting is not that different from the problem with a lot of representational painting, i.e. not so interesting, not so good.

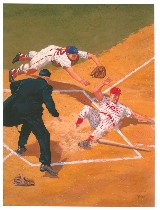

I’m thinking here about those Dick Perez baseball paintings coming to PAFA Jan. 7 to celebrate the new Phillies stadium. To me, this is lowest common denominator art, appealing to everyone who loves a representational picture–and baseball, I guess.

I’m thinking here about those Dick Perez baseball paintings coming to PAFA Jan. 7 to celebrate the new Phillies stadium. To me, this is lowest common denominator art, appealing to everyone who loves a representational picture–and baseball, I guess.

But imagine yourself 1,000 years from now. The game of baseball has disappeared from earth along with most of what we now call civilization. Someone finds one of these paintings, like this one showing Richie Ashburne sliding in to home. Surely, this would be mysterious to you. Who’s that scary-looking guy in black? Is the guy flying in the air an angel? Is he going to kill the guy who fell? Is the guy who fell someone special?

What seems today to be nothing more than a picture might seem like art in the distant future, having gained an openness that wasn’t there at the time it was painted.

I wonder how many Renaissance paintings or Medieval paintings gain their mystery from our ignorance. They make us wonder who that girl in the pearl earring really is, but perhaps, in her day, everyone knew who she was or what kind of person she was.

While enjoying pictures of the world is part of our nature, not everyone enjoys art more than snapshots. Why else would so many people own no art, not even prints and reproductions, which are cheap, and why else would so many people put up movie posters and snapshots of their friends, to the exclusion of art?

While enjoying pictures of the world is part of our nature, not everyone enjoys art more than snapshots. Why else would so many people own no art, not even prints and reproductions, which are cheap, and why else would so many people put up movie posters and snapshots of their friends, to the exclusion of art?

So art isn’t for everyone, even when it is representational. And abstraction has a smaller audience, yet. And it’s the size of the audience that gives art its best chances for survival. So you may be right, that abstraction is the Neanderthal of the art world — but not if the art world has its say:

Art museums are skewing the survival prospects of abstract art by having so much of it in their collections (shown, Hans Hoffman’s The Gate, part of the Guggenheim’s collection). Here, it’s the extremely informed art viewers who are making the choices and not vox populi. In truth, they may be too far into their theories and interest in paint’s materiality to notice that few others are looking.

Art museums are skewing the survival prospects of abstract art by having so much of it in their collections (shown, Hans Hoffman’s The Gate, part of the Guggenheim’s collection). Here, it’s the extremely informed art viewers who are making the choices and not vox populi. In truth, they may be too far into their theories and interest in paint’s materiality to notice that few others are looking.

So 1,000 years from now, when you discover a color field painting (shown, a Jules Olitski screen print) that survived the bombs down in the museum sub-basement, will you say, look at this giant color swatch for floor covering, or will you say om?

So 1,000 years from now, when you discover a color field painting (shown, a Jules Olitski screen print) that survived the bombs down in the museum sub-basement, will you say, look at this giant color swatch for floor covering, or will you say om?

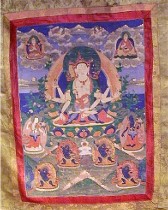

My guess is you will save the om for a Tibetan Tanka that takes you on a representational trip around its image and into the beyond.

My guess is you will save the om for a Tibetan Tanka that takes you on a representational trip around its image and into the beyond.

On the other hand, we have tons of pattern that we admire from other cultures, so why wouldn’t Futureworld admire ours?

Abstract is pretty hard to decode, and some of it seems just silly to me (I’m thinking Robert Ryman whites, Ad Rheinhart blacks).

But what do you make of Thomas Nozkowski (shown, Untitled)? I don’t think you’d throw him on the trash heap that readily.

But what do you make of Thomas Nozkowski (shown, Untitled)? I don’t think you’d throw him on the trash heap that readily.

.