Most visitors to Van Gogh Up Close at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA, through May 6, 2012, then at the co-organizing museum, the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, May 25 – Sept. 3, 2012) will be excited simply to see a large number of paintings by Van Gogh; he’s the artist most guaranteed to draw crowds and to send them home happy. This doesn’t pretend to be a survey of his work. It is, rather, a carefully-curated theme exhibition about an aspect of Van Gogh’s work that has, until now, been unexplored: the artist’s novel exploration of the closely-focused view. For the serious visitor, it offers both challenges and rewards, as the true subject is Van Gogh’s exploration of both vision and representation.

The paintings were produced during a time of changing visual culture, itself the product of increased trade and new technologies. Van Gogh responded, in particular, to three issues that engaged many artists of his day: an increased understanding of the science of vision, and color in particular; the opening of Japan, and the resulting circulation of Japanese prints; and the development of photography. The exhibition situates Van Gogh very clearly within this matrix by including a selection of Japanese prints he was known to have owned, and a group of photographs of trees and flowers, by mid 19th century photographers who are not well-known beyond specialists.

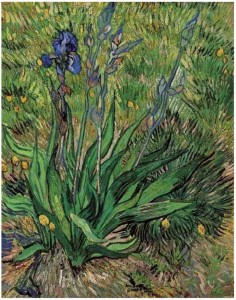

Van Gogh Up Close demonstrates three aspects of the artist’s practice that will interest serious students of painting. The first is that, despite creating the appearance of spontaneity, by the time he started painting Van Gogh had an extremely clear image of each composition, down to all the details; this is indicated by the very, very few instances of compositional changes that are found in his work. I found only one obvious pentimento (a change made during painting), revealed by heavily textured brush-strokes in one direction which are covered by brush-strokes in another. It appears in Iris (Ottawa, below) in the area at the top, between the stalks, and it is not absolutely clear what the original idea was (as it is an another painting of irises owned by the Getty, where Van Gogh painted a stalk and afterwards painted an open bloom on top of it).

The second aspect of Van Gogh’s technique which is clearly revealed throughout the exhibition is that almost all the paintings were created over multiple campaigns of work, again, despite their spontaneous, pleine-air look. While Van Gogh worked with wet-in-wet paint in many instances, he almost always returned to the paintings after the initial layer of thick and textured paint had dried (which may have taken weeks). Frequently he added outlines of very dark blue (or occasionally a brick red) to tighten up the forms, as well as making other additions over paint that had dried.

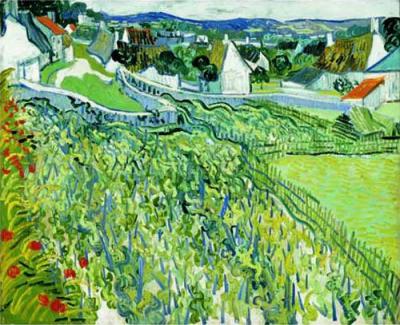

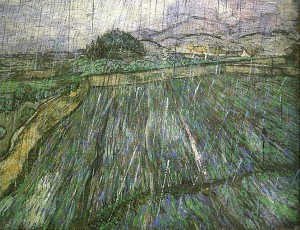

The third intriguing aspect of Van Gogh’s work is evident in only a few paintings which, rather startlingly, have no discernible focal point. They are the sort of all-over painting we associate with Abstract Expressionism; Pollock avant la lettre. Examples are Ears of Wheat, several paintings of undergrowth (both above; the exhibition contains a variant of Undergrowth, also from the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam), Acacias in Flower (Stockholm) and Dandelions (Winterthur). While the exhibition is organized around paintings which emphasize a close view, either zooming in on details or distant views in which there is equal focus on fore, middle, and backgrounds, that is not equivalent to these more radical, all-over compositions. Most of the close up compositions delineate forms by color, if not by increased clarity of focus, so that, while rejecting conventional devices to indicate recession, they still retain fore and back-grounds. The subjects of the all-over paintings exist in an undifferentiated space.

Two of my all-time very favorite paintings are included in the curators’ list of close-ups: Rain (PMA), and the larger version of Undergrowth (above, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam). I have tried to understand why they have such a hold on my imagination, when I wouldn’t usually describe Van Gogh as one of my favorite painters. I think it’s because both are attempts to represent atmosphere, rather than objects. In one case it is the sense of rain that activates ambient space, in the other it’s the play of light in a mostly dark and visually indistinct area beneath the woods. In these works Van Gogh paints the un-seeable, and in doing so evokes the other senses through which we perceive such phenomena: touch and sound. These paintings of no-things make us aware of the complexity of our perceptions.

One response to the exhibition surprises me, since the PMA usually installs work so beautifully that their efforts don’t show. I never thought I would complain of too much light on artworks (as a viewer, that is; as a curator I know better), yet a number of the paintings are so brightly lit that at first glance, the light bounces off the impasto, which becomes more prominent than the composition; I found it distracting. But this is a small quibble concerning a revelatory exhibition.