This weekend, all eyes are focused on the Parkway as the Barnes Foundation marks the opening of its new building and the arrival of its extraordinary art collection to Philadelphia.

Of course the biggest change for the Barnes — founded in 1922 by Albert C. Barnes as an art and education institution — is its move from a secluded residential road in Lower Merion to the city’s grandest avenue. But another change has been overlooked in the excitement: The new Barnes comes with a 5,000-square-foot special-exhibition gallery that is in some ways as important as the building and the collection.

Among the largest art galleries in Philadelphia, it will have a focus on contemporary work. “It’s a great opportunity for us to complement and illuminate the collection galleries,” said Judith Dolkart, chief curator for the space. “We can do exhibitions that use works of the artists in the collection and concentrate on one area, say nudes or still-lifes or art by African-Americans. And we can look at contemporary art the way [Albert] Barnes was looking at contemporary art.”

The inaugural exhibition, however, is not of contemporary work. Dolkart said that because there will be many first-time visitors to the Barnes’ new location, the show draws on the archives and includes artifacts and art that was collected but not displayed because it was not in the original wall ensembles that Barnes carefully installed to showcase his educational ideas.

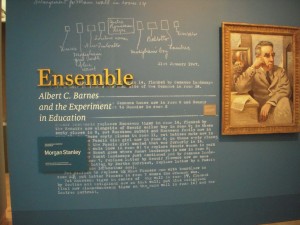

“Ensemble: Albert C. Barnes and the Experiment in Education,” up through March, lays out the story of the collector and the birth of the foundation.

“The title is a little double-entendre. ‘Ensemble’ is a wall arrangement and distinctive hanging style, and the exhibit looks at the ensemble of people around Albert Barnes,” Dolkart said. “It’s a rich, broad and textured group.”

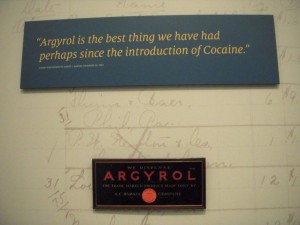

The show chronicles Barnes’ 40-year friendship with philosophers, educators, art dealers, collectors, artists and people from the West Philadelphia factory that produced Barnes’ invention Argyrol, the silver-nitrate drops that prevent blindness in newborn infants. There is material on Barnes’ wife, Laura, who was instrumental in creating the arboretum on the foundation grounds in Merion, where horticultural programs are still taught.

Barnes started his teaching program in the factory, where he’d display paintings and test students, some of whom had not graduated from high school. The exhibit includes an exam, with questions such as: “Is art an imitation of nature?” and “Are there different kinds of imagination?”

“The questions are really hard!” Dolkart said.

One of the workers, Mary Mullen, wrote a book, An Approach to Art, which also is in the exhibit. Mullen, who clearly had an aptitude for the subject, went on to teach seminars in the factory and at the Barnes.

The large, high-ceilinged new gallery, with blue walls and an oak parquet floor, has been installed chronologically with some free-standing partitions for extra display space. There are typed letters, in French, to Albert Barnes and a series of telegrams and letters on the purchase of Cezanne’s “Card Players.” Barnes spoke French, according to archivist Barbara Beaucar, but he wrote back to his French dealers in English.

A section of the show is dedicated to his zealous pursuit of African art, which drew African-American artists to the foundation. Handwritten letters from Horace Pippin and many others are shown in glass vitrines in the room, which has one small window at the floor overlooking the reflecting pool.

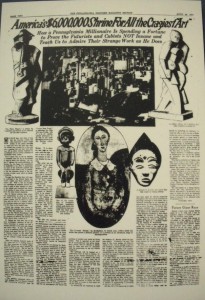

A reproduction of a 1923 Inquirer page is shocking for its scornful headline about Barnes and his “shrine for all the craziest art.”

“The archival show teaches how what Barnes collected was so radical,” Dolkart said. “We’re all accustomed to seeing Renoir and Matisse now — they’re like household names.”

Although most people are comfortable with Renoir, contemporary art can make people very uncomfortable. Dolkart said that working with contemporary art in the special-exhibition gallery will connect the institution to its controversial roots in the 1920s.

Dolkart would not share specific plans for what comes next in the gallery — “contemporary artists to respond to the collection” was all she’d say. Does that mean artists doing residencies at the Barnes? No decision’s been made on that yet, she said. “We’d love to have the collection galleries and the exhibition gallery in dialogue. We want to maintain the contemporary-art connection. Barnes was doing that.”

The Barnes opens to the public Saturday with 10 days of free admission culminating with 56 consecutive hours of access on Memorial Day weekend, May 26-28. Reservations are required and can be made online.

Education Sidebar

The Barnes has lots of new tools to help with its education mission. First among them are the two digital classrooms inserted between the collection galleries. Blake Bradford, Director of Education at the Barnes, said that in Merion, the classrooms were a jury-rigged affair in the administration building, nowhere near the galleries. But now, “If you want to pull up Cezanne images on the computer in the digital classroom and send students out to Gallery 8 (to actually see the Cezannes) you could do that.”

John Gatti, an eleven-year veteran instructor in art and aesthetics and initiator of the Art Now class at the Barnes, said, “Any work that predates or follows the collection, I can go and grab those images from anywhere on the Internet or from Art Stor (the art education database). I can include any artist I know now and any artist in a Philadelphia gallery.”

The work looks wonderful in the new setting. Natural light filtered through low transmission glass windows illuminates the collection as never before. The cloth-covered walls seem brighter too, as do the floors and the wood trim around the doorways. It makes a big difference. Gatti said the new lighting has changed how he will teach. He often overlooked some of the Renoirs in Gallery 18 because dim lighting hid their colors and they couldn’t compete with more compelling works in the same room. “I used to walk right by them and go to the Blue Picasso. Now, I stop and slow down and look. Now Renoir’s colors and the impressionist application (of paint) are manifest in every painting. It will change my teaching on color — there’s a psychological shift with seeing new color.”

The special exhibition gallery is another educational tool Bradford is happy to have on the Parkway. The first exhibit, “Ensemble: Albert C. Barnes and the Experiment in Education,” is not as sexy as the drama about the move to the Parkway, Bradford said, but he feels it’s a more important story. “There’s a sense of our legacy as a place with all these wacky stories and characters,” he said. “The stories about Barnes and the drama are fun for normal folks not invested in it. But Barnes took education seriously,” he said. And so does Bradford. “We are stewards of the mission. I look at that as our prime directive,” he said.

The Barnes Foundation, 2025 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, open 9:30 a.m.-6 p.m. Wednesday-Monday. $18 adults, $15 seniors, $10 students. Free first Sunday of the month from 1 to 5 p.m. 215-278-7160, barnesfoundation.org.

This article ran in the Daily News May 18, as part of Art Attack, a partnership with Drexel University supported by a grant from the Knight/NEA Community Arts Journalism Challenge and administered by the Greater Philadelphia Cultural Alliance.