Ralph Eugene Meatyard (1925–1972), working outside of a major art center and unaffiliated with any of the photographic movements of his day, produced that rare body of work that establishes an unforgettable, individual vision. The present exhibition, organized by the Art Institute of Chicago, is on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) through August 5, 2012. The almost sixty photographs were created in the last ten years of Meatyard’s life, which culminated in the fictional project, The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater. With the most straightforward photographic technique, Meatyard created unsettling work that questions notions of family, childhood, identity and memory.

Meatyard was well-read in Classical and contemporary literature (many of his friends were poets) and sophisticated about the history of photography. His work draws on the Romantic tradition of the pictorialists, and I suspect he knew spirit photography (photographs purportedly of ghosts). Yet his tone is closer to that of nineteenth-century American writers, such as Hawthorne, Poe and Henry James. As with the Lucybell Crater album, Meatyard photographed his own family, usually masked, and employed a series of dolls and mannequins (usually partial), all set in abandoned houses and overgrown landscapes, the ruins beloved by the Romantic imagination.

In one of the many untitled images we see a weathered flight of stairs with a small, toy horse perched on one step. To the side of the stairs, the bust of a female mannequin sits within a closet. The figure is clearly no more real than the horse, but the photograph sets up a poignant tension nonetheless, with its references to play and fantasy, commerce and death.

Meatyard understood that masks are associated with play-acting and partying (and in some cultures, with religious ritual and theater), but also with less benign reasons for disguise. His use of masks raises the uncertainty of who is behind them. Often the figure is obviously a child, whom we presume innocent, wearing a grim, and sometimes downright scary mask. None of the figures are in costumes, nor do they make any attempt to appear convincingly as someone else. Meatyard never asks us to suspend our disbelief.

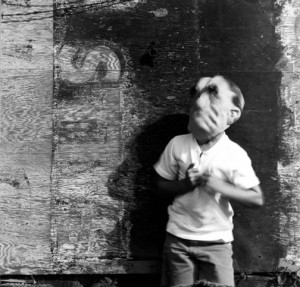

One series of photographs portrays an adolescent boy, dressed in shorts and a tee-shirt, and wearing a different mask in each until the last photograph, where he is mask-less but his face is blurred. The series evokes a common predicament of adolescence, searching for self-definition and perhaps running through various personae in the attempt.

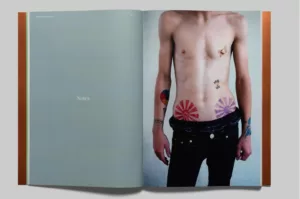

Some of the work has a creepy, erotic edge; the unclothed and dismembered mannequins are all female, the dolls are girls or infants, suggesting sublimated desire acted out with inanimate objects. In one image (above) the figure of a child wears the improbably-large mask of an old man as well as a fake hand, with a doll poking out of the child’s sweater.

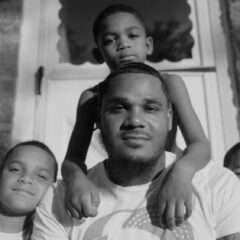

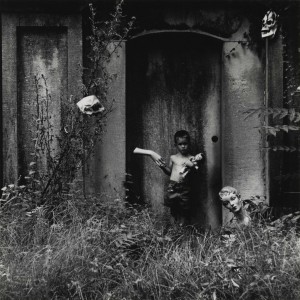

One little boy appears unmasked in several provocative scenes. In one he stands facing a wall and hanging his head; a fence beside the wall holds several masks and dolls, at the center of which is a doll with notably splayed legs. In another image (above) the same child holds out the hand and forearm of a mannequin with his right hand, as he clutches a doll in his left. Beside him sits the head of a female mannequin. This was a period when boys didn’t play with dolls.

One of the most evocative images contrasts the unmasked head of a woman who sits beside a piano with that of a masked child, playing the instrument. The woman’s eyes are closed in reverie, and it is unclear whether the incongruous mask of a man’s head which covers the child’s face is a projection of the woman’s thoughts, or the child’s own fantasy or disguise.

Meatyard said little about his work, but when he spoke about his use of masks he claimed that they turned the figures into generalized rather than specific people. But the masks he chose were either eerily blank, such as those of store mannequins, or exaggeratedly fierce and ugly – no clowns, harlequins or happy faces. I’d rather interpret the photographs based upon their own evidence.