The Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) has just opened a glorious exhibition celebrating painting and the twin subjects of myth and desire, which are behind so much great art. The myth in Gauguin, Cézanne, Matisse; Visions of Arcadia (through Sept. 3, 2012 and only to be seen in Philadelphia) involves Arcadia – a mythical land of contentment and harmony with nature that was conceived by the ancient Greeks and passed on via the Romans (most pointedly Virgil, in his Eclogues), Italian Renaissance writers and artists, and Poussin, a seventeenth-century French painter who spent almost all of his career in Rome.

Poussin is considered the founder of the great modern French tradition in painting, the principles of which were codified by the Académie des Beaux-Arts in the Seventeenth Century. The basis of academic education was drawing, especially figure drawing from nude models (such drawings were known as académies). A second myth central to the exhibition is that via the continuity of classical culture, the French are descendents of the ancient Greeks. These national originary myths became important to the founding of the modern nation-state; in fact, the Germans, too – with the help of Winckelmann – claimed descent from the Greeks, until Napoleon invaded, and they had to re-invent their mythical origins.

Desire, in the exhibition, is for a land of endless food, drink and sexual fulfillment, where humans lived in harmony with nature. Vergil’s Eclogues depict Arcadia as always shadowed by death, as does Poussin; one of his best-known paintings shows a group of Arcadian shepherds looking at the inscription on a tomb which reads: Et in Arcadio Ego – loosely, Death, too, is in Arcadia. But for most modernist painters, Arcadia was usually depicted as a pagan Eden, without the threat of sin, expulsion, or any consequences of overindulgence. In modern Arcadia it is always a sunny day, a land of outdoor picnics and daytime lovemaking.

The exhibition has five galleries of extraordinary work, and several galleries would make satisfying exhibitions on their own. The opening corridor-like space contains the sort of intimate pieces one might find in the home of a discriminating collector with a taste for the decorously erotic: Cézanne’s small painting of nude, female bathers beside the water, and Henri-Edmond Cross’s nude faun, dancing as he eats from the bunch of grapes he dangles above his own head. Then Rodin’s small plaster sculpture of a lascivious faun who has captured a less-than-willing nymph; Rodin is always good on desire, but mutual consent wasn’t his concern. The gallery also displays two livres deluxe, one with buoyant etchings by Matisse, illustrating Mallarmé ‘s poems, the other with somewhat more sober woodcuts by Maillol, illustrating Virgil’s Eclogues.

The second gallery holds a group of work that constitutes a study of continuity and variation in nineteenth-century French painting. The first work is a Corot cliché verre, itself a new printmaking technique dependent on the chemically-treated paper used in photography. But the emphasis of the gallery is on a group of large paintings intended to function as wall decorations, some of them done in obvious emulation of frescoes. These include Corot’s Silenus, which takes its subject directly from Virgil, and two large idyls by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. Puvis is an artist to be reckoned with because, to the bafflement of many later observers, his classicizsing narratives, the last gasp of that tradition, had a significant impact on the avante-garde of the following generation. That his calm and lifeless figures should inspire artists of great daring and ferocity has not been explained to my satisfaction. The best I can understand his impact is that later painters saw in Puvis’ work (and not necessarily his intentions) that the ostensible subject matter was less important than the means of expression; the emphasis was on painting itself.

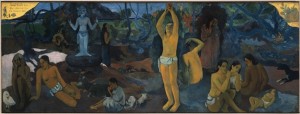

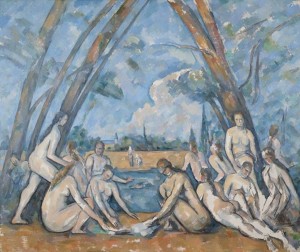

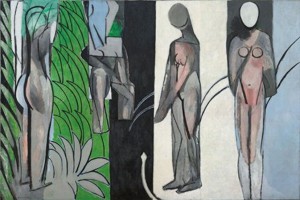

The next, grand gallery is the heart of the exhibition, and if it weren’t actually there, I might be describing the fantasy group of paintings any curator of the period would like to assemble. The fact that PMA Curator Joe Rishel obtained these loans is testimony to the enormous, international respect that he and the museum have earned. It is to the viewers’ great benefit, for they are a series of towering works, each worthy of serious study; but more than that, as explained in detail in the exhibition catalog, there is reason to suggest a direct back and forth relationship not only between many of the painters involved, but between the actual works on view. They include not only the paintings around which Rishel organized the exhibition: Cézanne’s Large Bathers (1900-06, PMA), Gauguin’s Where Do We Come From? Where Are We? Where Are We Going? (known by the beginning of it’s French title as d’ou Venons-nous? 1897-98, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), and Matisse’s Bathers by a River (1909-17, Art Institute of Chicago), but also Henri Rousseau’s The Dream (1910, Museum of Modern Art, New York), André Derain’s Bathers (1907, MoMA, NY), and most astonishingly, Poussin’s Apollo and Daphne (1664, Muséé du Louvre, Paris).

In addition to the wonderful opportunity to observe the paintings in proximity to one another, it is a joy to see the Cézanne and Rousseau, in particular, benefiting from the generous spacing and good lighting of the installation. I have never seen them look so good (indeed, never had the opportunity to study the surface of the Cézanne, as usually displayed – and it is a pristine surface). In terms of the exhibition’s theme one has to ask, why this subject then? And why such monumental paintings? The previous avante-garde had pointedly rejected the hierarchies of the Academy, which considered still lives and portraits beneath consideration, landscapes a lesser genre, and valued only history painting: paintings of figures depicting scenes from Biblical or Classical stories or actual events, such as Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa. These have been called the grand machines of the French tradition, and only Manet attempted the genre (traditionally with the Execution of Maximilian, and in abased form with his Dejuner Sur l’Herbe and Olympia).

This return to majestic history painting certainly raises the question of what turn-of-the-20th century painting should be and do, and where it fits within the history of art. The paintings by Gauguin, Cézanne and Matisse stand out in scale and ambition, exceptions within their oeuvres. We know that Gauguin considered the d’ou Venons-nous? as his masterpiece, his bid for consideration as a major artist. The Cézanne is the largest of three large paintings of a subject he had returned to throughout his career; it was left, possibly unfinished, in his studio when he died. And Matisse troubled himself over Bathers by a River in three periods over eight years, with very substantial changes over time (all recovered through technical examination). Gauguin based his painting on a complex but entirely personal iconography, he didn’t expect it to be understood figure by figure; but with its span of humanity from near birth to near death, it is obviously his story of human life, and the only one of the modern Arcadian works that retains the clear presence of death. It is hard not to see the grandeur and ambition of these paintings as competition with the French old masters, bids for consideration as important painters whose work should join their predecessors in the Louvre. They certainly understood that tabletops of apples, genre scenes or studies of light on a church facade would not hold up to Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People.

The exhibition’s following room holds a group of Cubist works by Delauney, Gleizes, and Metzinger (and pre-Cubist drawings by Picasso). They demonstrate the unlikely continuation of the subject matter, but the gallery is a let-down after the riches of the one before it. It also contains a beautiful late Maillol sculpture (in lead) of three nymphs, done in 1930-38, which is perhaps the last time such a subject could be approached without scorn or irony.

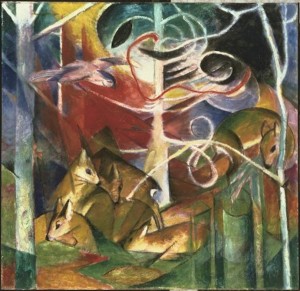

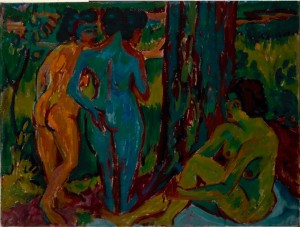

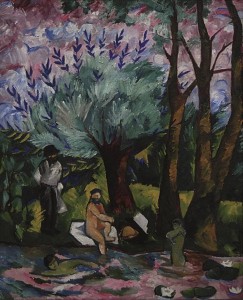

The final room forms an intriguing coda, for it presents a group of German Expressionist paintings and two by Russians, that show the Arcadian tradition beyond France. Boys Bathing by Natalia Goncharova displays the exhibition’s one spot of humor, for on the riverbank sits a male figure holding his bent knee, surely a citation from Manet’s Dejuner Sur l’Herbe, but Goncharovna has stripped him of all of his clothes but his black cap. The Germans had their own contemporary enactment of Arcadia; Naturist groups were common during the period and artists had nudist holidays in the countryside. We see paintings of their activities by Kirchner and Pechstein. There are also several of Franz Marc’s utopian idyls, the last dated 1913. Following World War I and the horrors of modern warfare, the myth of Arcadia had lost its promise.

Note: The American painter who most used the Arcadian subject was Arthur B. Davies, who was also one of the few who had traveled to Europe at the time. The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) has one of his paintings of nudes in an Arcadian countryside, from 1910, on view through July 8 as part of an exhibition about PAFA and Albert Barnes.