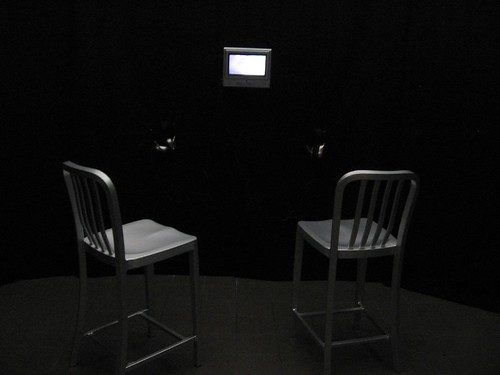

Judy Gelles’ video interviews about age, that show only the subjects’ mouths

Perhaps I was in the perfect frame of mind for taking a good look at what two Philadelphia artists are showing at Moore College, in tandem with a group show that includes a large number of internationally known artists.

The two artists are in Encapsulated Time: Age, Image and Rock ‘n Roll in the Levy Gallery at Moore. The two couldn’t be more different from each other. One of the artists is Judy Gelles, who’s from my age group and is well established in photography and video. She is known for using her own life to tell stories about time, family, gender and other identity issues. The other is Andrew Suggs, just a few years out of Harvard (AB cum laude), who recently joined Vox Populi and was in Fleisher/Ollman’s emerging artists exhibition Morgellons last year.

detail from Andrew Suggs’ 6-channel video installation of music listeners

But both of these very different artists are using video to dig beneath the skin that so defines us, and reach into the mind–the part of us that knows no age.

What put me in the excellent frame of mind was my visit to the adjacent gallery at Moore. In Repose, an exhibit of photographs, videos and sculpture drawn by Curator Lorie Mertes from the collection of Dennis and Debra Scholl, includes work by women about women, and it’s not to be missed.

Pipilotti Rist, who came out of pop singing, subverts a music video to her own purposes with I’m not the Girl who Misses Much

collection Debra and Dennis Scholl

In Repose explores femininity, identity, and sexuality–and by extension, it explores how the images we’re so used to of women from the historical past and from the pop-culture present are not necessarily how women see themselves.

But that is too narrow a description of this show, full of terrific images that overturn stereotypes by satire, anger, and every other strategy possible.

Tanyth Berkeley, Grace in Window 2006, C-print, explores atypical-looking women in her photographs, moving them from real life into photoraphs, thereby broadening our view of who should serve as a subject

collection Debra and Dennis Scholl

In the context of women’s traditional role as subjects projecting some male image-maker’s fantasy of sexual perfection, and in the context of women’s culturally exaggerated fascination with the impression their appearance gives, each of the works in In Repose was frought with multiple messages.

The false standards for beauty and what women really look like are the subject in Tanyth Berkeley’s portraits.

Bettina von Zwehl, Untitled 1, from the series Untitled 1 (Sophy) 1998; (right) Untitled 2, from the series Untitled 1 (Charlie) 1998

C-print on aluminum

collection Debra and Dennis Scholl

Bettina von Zwehl’s large portraits of women just awakened from sleep also seem to be trying to scratch away the surface to reach some kind of understanding of the person beneath, before they put their day faces on.

Mariko Mori, Miko no Inori, 1996

video, color, sound

collection Debra and Dennis Scholl

Pipilotti Rist’s bare-breasted music video on speed and helium is a hysterical challenge to cultural expectations of how she ought to be behaving and dressing and relating to male love expectations. Mariko Mori‘s other-worldly perfection in her music-video-inspired Miko no Inori reflects fantasies of female identity and projects them into a fantasy future. It took my breath away, with its slick, commercial-like production and its bald-faced unreality that simultaneously creates and undercuts its own falseness in one fell swoop. (I also have to mention the elegant, futuristic installation in the mint green room, visible and audible from the street).

Anna Gaskell, Floater 1997, 16mm color film transfered to DVD

collection Debra and Dennis Scholl

Anna Gaskell‘s Alice tumbling down the stairs in her perfect good-girl outfit with immaculate white tights questions with gentle humor the whole sybolic paradigm of Alice falling down the rabbit hole, just as Gaskell’s Floater projection on the floor re-examines the romanticized death/madness-of-the-innocent paradigm of Ophelia. By entitling it Floater, she brings up the brutality of police jargon, and reestablishes Ophelia’s death as anything but lovely. (I don’t see victimization in either of these pieces; rather I saw a rejection of victimization. I did a survey while I was there and found only a few that I saw as victimization of women all over again).

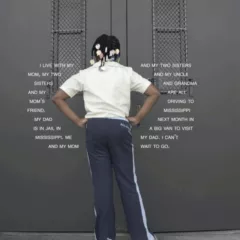

Andrew Suggs, installation shot, showing of five of the six channels of preoccupied karaoke singers

I carried those thoughts with me when I walked into Suggs’ video installation of young men and women singing to themselves, often tunelessly, as they listened with earphones to rock ‘n’ roll. The utter lack of self-consciousness of the subjects, all ears, lost in the rock music they are hearing, is a rare peek at young people, who generally spend a lot of time considering how to look, how to confront the world, how to seem cool, and how to attract a sexual partner. Here, the balanced tips toward their interior life and away from their exterior self-presentation.

Mostly when we see people sing, they are performing at some level. These subjects are so engrossed with what’s in their minds that they sing along tunelessly in perfect anti-performances. How each of the subjects looks falls away here. To have each of them be the star of such an anti-music video is a conflation of 15 minutes of fame and a commentary on the superficiality of the fame, all at once. It’s innervisions without production values. It’s the way we look to us all–questioned on multiple levels.

And it brings to mind Kutlug Ataman‘s political 40-channel video installation of soliloquys by the rarely noticed residents of an Istanbul shanty town. It used ordinary televisions and a sense of being in a place where people really live and think thoughts not necessarily part of the cultural stream of images we absorb daily.

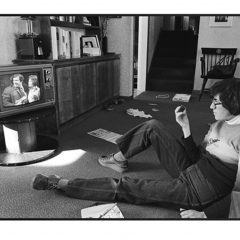

Suggs’ use of ordinary-looking televisions also challenges the societal image of the slick world of every home with a mega HDTV tuned to the slick imagery of the commercial television world. On this Superbowl day of extreme commercials, I feel like I’m writing about what’s happening on my own television right now.

The other two works in the exhibit are by Gelles. One is a video of close-cropped mouths speaking about how they feel about their age–and therefore their lives. The speakers are all artists of various ages and media from visual to music whom Gelles filmed while on an artist’s residency. By eliminating so much face, Gelles takes away most of the visual identity of her subjects. Gender comes through (but not sexuality); age comes through only partially. But tension around the mouth is part of the package, along with small details of skin, lips, teeth. So little information is there that the words become almost disembodied, and some of the younger artists have old heads and vice versa.

The means of presentation brings us into people’s inner lives, and gets us past the physical lies of beauty, clothing, and self-presentation. Yet we definitely are not listening to radio. The visual still has a role, but it teases with less information than we are used to. But we get a lot of aural information–of what people consider a life worth living as well as the values placed on youth and age.

That Gelles wears a hearing aid makes the focus on the mouth less surprising. When I first spoke to her about this video, around a year ago, she said that she hadn’t had that thought while making the decision to crop close to the mouths, and it wasn’t until someone pointed it out to her that she realized the relationship to lip reading.

Judy Gelles, her parents and her husband and boys when they were young.

Gelles’ other piece is a series of photographs of her and her family (her mother, father, herself, her husband and her two sons), taken annually in the same arrangement, same spot (in Florida, her parents home). While the setting and the configuration of the people remains as much the same as possible through the years, we get to watch the boys grow up, the older generations age.

Judy Gelles, her husband and her mother, in recent times.

People disappear from the picture–death takes Judy’s father, the boys, now men with adult work obligations, aren’t there some years. The series is a moving document of all our lives, and raises the family-on-vacation, family-reunion snapshot and the family portrait to something profound and meaningful. In the context of all the single-person portraits in In Repose, Gelles’ work looks sane and social. It makes the art next door (in In Repose) look awfully hermetic, sterile and self-absorbed.

By the way, Gelles is one of the three artists in the Challenge #4 exhibit at Fleisher, opening Feb. 15.

Kudos to Mertes, who curated these two shows and brought together this unexpected pairing of age and youth.

By the way, my response to In Repose was quite different from Andrea Kirsh’s. If you missed what she had to say, here’s her post.