The commissioner of documenta XIII, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, treated the entire ground floor of Kassel’s Fridericianum (a Neoclassical building from 1779, designed as one of the earliest public museums) as her introductory statement to the 300 plus-artist exhibition centered in Kassel, with outposts in Kabul, Alexandria and Banff. When I reached the phrase in the first label …, suggesting a particular mode of proximity by way of the spacially diffused aggregation of elements that also maintain their own singularities, I realized that the reading, at least, would be hard going.

To the right, the large but sparely-installed gallery contained three small, bronze sculptures by Julio Gonzalez and an installation by Ryan Gander. The same Gonzalez works had been shown in the second documenta in 1959, and their reprise here was intended as a recapitulation of the work of sorrow that documenta historically carried out in the realm of art and culture, following global destruction, during the reconstruction of Germany and Europe.

Accounting for the legacy of the Second World War was a repeated subject of documenta XIII, but one that surprised me, since the War is woven so inextricably into the urban structure of modern Kassel. The city, with buildings erected when it was the center of a royal principality, was massively bombed because it was the site of factories that produced planes, tanks and train equipment for the Third Reich. It was subjected to a second destruction in the 1960s by a dreadfully-conceived rebuilding that privileged cars over pedestrians in the city center.

Ryan Gander’s work was identified by a wall label as I Need Some Meaning I Can Memorize [The Invisible Pull] ( 2011), and it soon became apparent that Gander had engineered the slight breeze that swept through the entire ground floor of the museum. As welcome as the air flow was, I couldn’t help thinking of the rather hackneyed metaphor, “the winds of change,” as well as of Michael Asher’s Vertical Column of Accelerated Air (1966-67), which created a more localized air stream as its sole physical manifestation.

The other works on the ground floor were Ceal Floyer ‘s repeated rendition of an excerpt from the Tammy Wynnette song, I’ll just keep on until I get it right, John Menick’s sound piece involving subliminal messages so effective that they escaped my conscious notice, and the video, Picasso in Palestine by Kahled Hourani with Rashid Masharawi and Amjad Ghannam, which documented the loan of a Picasso painting from Eindhoven to Ramallah, bringing together the twin subjects of art and armed conflict which Christov-Bakargiev made the focus of her mini-exhibition in the Fridericianum’s rotunda.

Lawrence Wiener’s The Middle of the Middle of the Middle (2012) was inscribed on the glass wall that marked off the rotunda, which had been designated as documenta XIII’s brain; standing alongside the glass was a line of visitors in the ironic position (given that most of the contemporary work in documenta XIII had at least some conceptual basis and a strong political slant) of waiting to be allowed into the rotunda to see an exhibition centered around a group of small still lives and landscapes by Giorgio Morandi, an artist who, like Matisse during the first World War, worked in his studio throughout the conflict.

This brain of documenta XCIII, which Christov-Bakargiev called an associative space of research contained a lot of fascinating work, but it was presented as an essay illustrated by objects; and at this point, I decided I’d read enough. The selection included several editions of Man Ray’s Object to be Destroyed, emphasizing the lingering significance of a lost, original artwork; a ceramic vase by Catalan painter Antoni Cumella, who sought universal truths in abstraction during the 1940s-50s (a search that by then was half a century old); video footage by Egyptian artist Ahmed Basiony, made in Tahrir Square the day before he was killed by police snipers; the fused remains of objects from the National Museum in Beirut, damaged during the civil war; and a group of small, Bronze Age figurines from present-day Afghanistan which raised the issue of both our interest in finely-wrought objects and their contingency upon their surroundings. The works were certainly interesting, but using art to illustrate a thesis is better left to articles. The overarching theme, which would reappear throughout documenta XIII, concerned the possibilities of art and artists in a world at war and/or facing enormous problems of mankind’s making – and the risks to both artists and their work. The theme is certainly compelling and timely, but I’d rather hear it from the artwork.

The rest of the work in the Fridericianum was left to speak for itself, and the most impressive did so loudly. Ida Applebroog occupied considerably more psychic space than the large gallery that she filled with a wall installation and a warehouse worth of printed material, offered for visitors to take. It was great to see an artist in her eighties make such a feisty impression, and she was just the first of the women that Christov-Bakargiev included as significant predecessors and models for current artists; others included Emily Carr (1871-1945), Joan Jonas (b. 1936), Maria Martins (1894-1973), Lee Miller (1907-1977), Margaret Preston (1875-1963), and Charlotte Salomon (1917-1943).

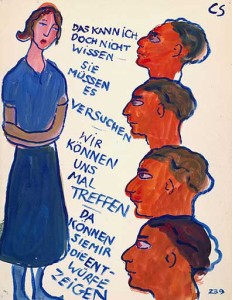

One large body of work that made a significant impression was Charlotte Salomon’s Life or Theater? A Play with Music (1941). The 769-image narrative fused extensive texts and illustrations (in gouache on paper) in a format of Salamon’s invention – neither script nor novel, it bears some resemblance to film story-boards; she called it a Singspeil – a German form of opera with spoken dialog. The work is a fictionalized interpretation of the artist’s family history and her own experience as a young, Jewish artist attempting to make art under Nazism. I was fortunate enough to install the series when it first traveled to the U.S. in the mid 1980s, and it is just as powerful on the second viewing.

Another large gallery housed work by Doreen Reid Nakamarra and Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltarri, two Australian Aboriginal artists who interpreted traditional themes, known only to community insiders, in large paintings on canvas intended for outside audiences. The imagery, stunning for its abstract patterning and formal qualities, represents ancestral history and ties to the land; this is art with a proven political history, as such representations have been used successfully to demonstrate Aboriginal land claims in Australian courts.