While in Dallas for the College Art Association annual meeting I managed to slip away to see some art. At the Dallas Museum of Art was a small exhibition, Leonora Carrington; What She Might Be, containing twenty-five works by an artist some ten years younger than Lee Miller and Frida Kahlo, both of whom she knew ( both currently have exhibitions at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA), see post and post). The English-born Carrington, who is celebrating her ninetieth birthday, is another woman who used her beauty as entree into the artworld. At nineteen she fled her proper bourgeoise upbringing (she’d been presented at court to George V) to go to Paris with Max Ernst where they were part of the Surrealist circle. Fleeing the Germans she ended up in Mexico City in 1943, as did a number of other Surrealists, and became a close friend of the expatriate Spanish artist, Remedios Varo.

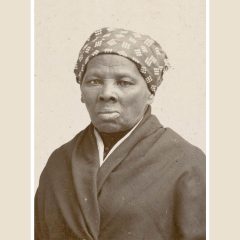

Country House, 1957, oil on canvas, 34 1/2 x 26 1/2 inches, private collection, photo courtesy of Dallas Museum of Art

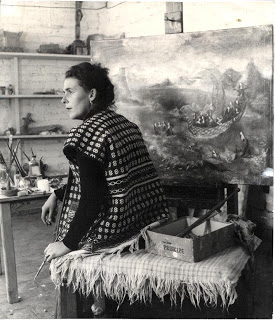

As with the Kahlo exhibition (organized by the Walker Art Center and currently at the PMA), the Carrington show contained numerous photographs of the artist (presumably from her own collection), picturing her with family and friends, from infancy to maturity. This much emphasis on biography is unusual in art exhibitions; while Frida concentrated on self-portraiture, Carrington didn’t. Don’t know whether it’s audience demand or curatorial choice, but I can’t think of a male artist who’s been presented this way.

Carrington’s touch is delicate and her imagery dreamy and fantastical – a sort of Magic Realism avant la lettre (that is, Magic Realism as used to describe a strain of Latin American literature; the term was used in the 20s and later to describe paintings that were more hyper-real than surreal). Altogether her work has an illustrational quality; in fact, she both wrote and illustrated books. Some of the modest ink drawings have entertaining titles, such as The Fall of the House of Mink. The one painting that has a compelling interest for its paintwork is Country House, largely done with thin, chalky, white paint for both background and central image. The house lost in mist and foliage is both lyrical and mysterious; it has some of the elusive qualities of Armando Reveron’s evanescent white nudes.

Double Portrait (Self-Portrait with Max Ernst), 1938, oil on canvas, 25 3/4 x 32 1/4 inches,

Rimrock Foundation

Double Portrait intrigued me because of its unfinished state. Unfinished paintings offer the clearest view of how an artist works. In this self-portrait with Ernst in the bird costume of his alter-ego Carrington began by sketching the figures in fluid brown paint on a mid-toned, tan ground. She filled in the faces and some of the figures but stopped before painting her legs or any of the background.

Upcoming Talks on Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo

Susan Alberth, author of the only substantial monograph on Carrington available in English will be speaking this Saturday, March 8 at 3 pm at Taller Puertorriqueño, where on May 3rd, Janet Kaplan will discuss the work of Remedios Varo.

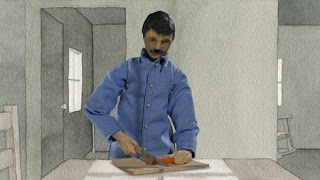

Joshua Mosley still from A Vue, 2004, mixed-media animation, high-definition video, © Joshua Mosley

I made a quick visit to the Museum of Modern Art Ft. Worth where, in addition to seeing the new building by Tadeo Ando and a prime collection of painting and sculpture from the 1950s-70s, I caught a solo exhibition of Philadelphian, Joshua Mosley. A Vue, a high-definition animated video projected onto a large screen was shown along with a 24 inch bronze sculpture of George Washington Carver (that reads as a colossus in the video, see detail above) and a number of ink wash and charcoal sketches.

Joshua Mosley still from A Vue, 2004, mixed-media animation, high-definition video, © Joshua Mosley

Mosley’s use of music (an original score by Abby Schneider) and somewhat elegiac tone recalls William Kentridge’s Felix Teitlebaum series, but his clay-mation figures before painted backgrounds and tale of life decisions and lost opportunities is his own. The eight-minute piece set in George Washington Carver’s birthplace involves a park ranger, who cares for the huge Carver monument, and his abortive relationship with a scientist who has moved to the town. It’s a sort of modern-day Brief Encounter, with commitment to work rather than family coming between the couple. Despite having to stand to view it, the video attracted a large and well-deserved audience.

Joshua Mosley still from A Vue, 2004, mixed-media animation, high-definition video, © Joshua Mosley