Post by K-Fai Steele

Kansai Yamamoto, Bodysuit, 1971. Photo courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The Hello Fashion! Kansai Yamamoto 1971-1973 show at the Philadelphia Museum of Art is hidden in the Costume and Textile Study Gallery on the 2nd floor of the Perelman building. Yamamoto, a Japanese fashion designer known for his bold, extravagant stylistics, can be described with the Japanese colloquial word hade, meaning gaudy or something that stands out. He draws inspiration from Japanese national culture and tradition, specifically Kabuki theater, kimono, art from the Azuchi-Monoyama period (1568-1603) and marries it with Western (as in Amero-European) cut-to-fit tailoring. He is perhaps best known for designing the wardrobe for David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust persona, 1972-1973 (though none is on display).

The Philadelphia Museum of Art is showing nine of Yamamoto’s pieces from a 1971-1973, highlighting his sense of Japanese tradition and play in the materials and cut of the pieces. The colors are bright, the silhouettes are sexy. Yamamoto once said, “I am making happiness for people with my clothes. If you walk through Central Park in them you create a ‘wow.'”

Kansai Yamamoto, Cape, bodysuit, clogs, chaps 1971. Photo courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The cape is covered with appliqués (cut-out decorations sewn or embroidered onto the base textile) depicting popular Kabuki characters and an image of a Japanese mask kite. The clogs, also known as okobo or geta, are traditional sandals worn by apprentice geisha in the summer.

A New York Times article “Japanese Women: From ‘Geta’ to Platform Shoes” reports on the incidental trend of platform shoes in 1974 Japan: “…that balancing skill is now for sandals up to five inches thick and is as essential here to the popular mini-length skirts as the geta are to the kimono.”

Kansai Yamamoto, Playsuit with arm guards, leg guards, and red felt hood (1973). Photo by K-Fai Steele.

The hotpants playsuit is made from indigo printed cotton, a textile traditionally used for yukata, the Japanese summer kimono. The red felt hood is inspired by the traditional Japanese firefighter’s uniform, and flips up to reveal the face. Yamamoto often drew upon easily identified work vestments traditional in Japanese subcultures of conformity.

Japanese firefighter hood, Edo period. Photo courtesy of Tokyo Fire Department.

Yamamoto’s collection debuted in the United States in 1971 at Hess’s in Allentown, Pennsylvania when he was 27 years old. Hess’s donated the pieces to the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1974.

Hess’s on Hamilton Street 1897-1996. A bright, impressive Hess brothers marquee, once touted as the largest retail sign outside of New York, lured customers through the door. Image from Remembering Great American Department Stores.

Hess’s, the “Hollywood on Hamilton,” was at the forefront of couture from the 1940s to the late 1970s. Max Hess Jr. and later Irwin Greenburg (both Presidents and CEOs) made a practice of sending buyers to Europe and Asia to report back on current fashions. “We sent buyers all over the world to get the most unusual clothes that people would never expect to see in Allentown, Pennsylvania” said Greenberg, “the more extravagant the better. Something that everybody would say, ‘Oh my god, who would wear it?’ Why did we do it? People would talk about it.” It was a savvy marketing strategy. “We didn’t [sell couture items] to make money, we made money on the ten dollar men’s shirts, but the imports were all done to make the store an exciting place to shop.”

Hess’s gained notoriety for selling items such as Yamamoto’s clothing and Rudy Gernreich’s topless bathing suit, first modeled at Hess’s in 1964. (Hess’s didn’t sell a single topless bathing suit, but their marketing department drafted a press release stating that they had sold out, making national headlines).

Gernreich’s topless bathing suit, 1964. Worn by Peggy Moffitt (Gernreich’s muse). Photo by William Claxton.

Yvonne Burbage was one of Hess’s buyers who went to Asia in 1973 and bought Yamamoto’s designs along with pieces from four other designers (20 pieces total) for $7,000. In a typed transcript between Burbage and Greenburg, Burbage wrote, “We’re tired. These people drive me insane. It’s worse than Russia” and quickly went on to rave about Yamamoto, “We got nine pieces from Kansai. Exciting, traditional Japanese, very up to date.”

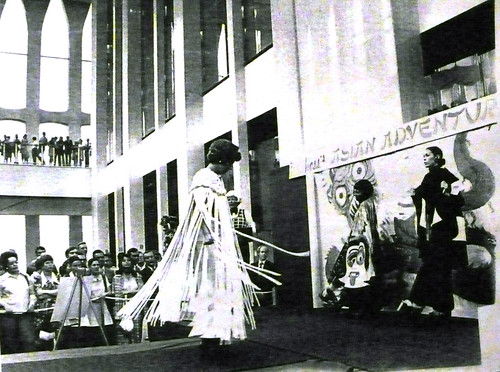

Hess’s often had community benefit fashion shows, and in September of 1971 advertised in the [Doylestown] Daily Intelligencer that Yamamoto’s pieces would be featured at Lenape Jr. High School in Doylestown: “introducing the new layered look, tent and smock fashions, the Oriental influence, and other trendsetters for fall and winter” (also featured were designs by Yves St. Laurent and Christian Dior). In an April 1972 article in the Bucks County Courier Times, another fashion benefit for the PTA in the Churchville school auditorium: “Boyish, bare and beautiful”. Burbage was quoted in a 1973 press release for another fashion show featuring Yamamoto, “More interesting, more excitingly feminine than I’ve seen in the past few seasons in European fashion collections.”

Image from a Yamamoto show held by Hess’s. Photo from the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

In the PMA’s exhibit is a video of Yamamoto’s 1971 first international Tokyo/London fashion show. It’s quite theatrical and the influence of Kabuki theater is obvious. The first model is wearing a large, red wig, which traditionally a red lion deity’s character would wear:

Compared to this footage of white and red, father and son lion deities:

Yamamoto utilizes the device of kuroko, stagehands wearing all black to conduct the models to walk forward, or begin spinning to show off a particular piece. They also assist with hayagawari, or quick costume change. Hikinuki or bukkaeri occurs when costumes are layered over another and the stage hand pulls one off to reveal another.

The device of hayagawari, at 50 sec. from Yukinojo Henge in a short piece of ‘Sagi Musume’ 1959:

And in a Disney live theater production, where one wouldn’t normally expect to see a traditional kabuki element utilized (at 1 min 14 sec):

The 1971 Tokyo/ London fashion show was where David Bowie first saw Yamamoto’s work:

[Kansai] was half out of sci-fi rock and half out of Japanese theater. The clothes were simply outrageous and nobody had seen anything like them before… The clothes were the brainchild of Kansai Yamamoto. Extraordinary designer… He contemporized the Japanese Kabuki and made it work for rock’n’roll.

The Hello Fashion! show contrasts his designs to three of his contemporaries, Rei Kawakubo, Issey Miyake, and Yohji Yamamoto (no relation), highlighting Kansai Yamamoto’s over-the-top stylistics. Their work tends to be much subtler, expressing jimi quietude in the wrapping and cloaking of the body.

Japan fashion offered adaptability with the kimono which focused on layered cushioning and abstract shaping, a garment that expanded beyond the human form and became autonomous, increasing the primacy of textiles and patterns. One could say that the Japanese didn’t focus their fashion entirely on sex and the body-penumbra silhouette like the west had for centuries. In his 1995 article “Our Kimono Mind: Reflections on Japanese Design: a Survey since 1950,” author Richard Martin wrote, “Western culture has inhibited any thorough investigation of fashion’s primary purposes.” Japanese design of the ’70s and ’80s offered a different perspective on clothing to Western fashion, which traditionally associated dress with specific times of day and activity (e.g., daywear is conservative, eveningwear extravagant). Clothing is made-to-fit. “Japanese fashion educates us to another approach to the body, beyond the sexual obsessions of the west.”

Kansai Yamamoto is a somewhat controversial fashion figure in Japan precisely because he embraced Japonism, updated it with cut-to-fit tailoring (and hotpants), and packaged it wholesale to the west. He could almost be called the John Waters or the Jeff Koons of Japanese fashion, exporting Japanese “vulgarity” to a world who thinks of Japan as lantern festivals, bright colors, and kabuki costumes. Richard Martin wrote, “As in every previous Japonisme, the West has viewed elements of Japan that are most traditional as radically new in their alternative to Western convention and has perceived Japanese innovation and custom alive as an iconoclastic vanguard.”

Yamamoto is certainly a businessman: not only a fashion designer, he has also wrote books, films, designed furniture, eyewear, dolls and doll dresses, even a Kansai Barbie. He had fashion shows (“Super Shows”) on a Cirque du Soleil/Beijing Olympics Opening Ceremony scale from 1993-1999. Video of these is on view in the PMA Study Gallery, and should not be missed. In March of 2008, Toshiba introduced a limited-edition luxury handset phone with custom-made cases created in collaboration with Kansai Yamamoto. The phones sold for ¥399,000 or $4,000USD.

The Hello! Fashion show at the Philadelphia Museum illustrates Kansai Yamamoto’s melding of Eastern and Western culture. He brings together traditional Japanese garments with contemporary western idiomatics, elements of kabuki costume with American hotpants. The following advertisement that Yamamoto was a spokesman for seems to sum up his junction between East and West –Japanese theater and coffee: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X1mIRbzN_NY (Nescafe Gold Blend ad, 1982).

Hello! Fashion: Kansai Yamamoto, 1971–1973. Through Wednesday, April 1, 2009 at the

Philadelphia Museum of Art, in the Perelman Building, 2nd floor Study Gallery.

–K-Fai Steele is an artist and edu-culturalist whose work can be seen at www.K-FaiSteele.com. She will be giving a lecture at the Philadelphia Institute for Advanced Study (www.PIFAS.net 1712 N. 2nd Street, Philadelphia) on Saturday, Oct. 18 at 8:30 p.m.