Post by Max Mulhern

The 1959 signature work by Mark Rothko in a small space.

Yesterday, in London, I visited the Rothko show of late works at the Tate Modern and a Coptic icon show in a gallery called Sacred Space.

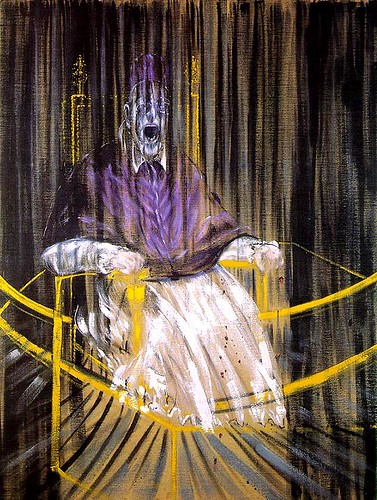

At first glance the Rothko show appears to be a disaster. The first room shows us a signature work from 1959. But it is hung in a tiny space so instead of walking into it we slide along it. Next we enter a vast space filled with thirteen canvases six of which were originally destined for The Four Season’s Restaurant in NYC. They are all hung 6’ off the ground and lit so as to render them invisible. We are in awe at the misrepresentation until we learn that Rothko intended for the works to be shown this way! (They were previously shown at the same height at the Whitechapel art gallery in London in 1961). Thus we are denied the trademark Rothko experience by which we are surrounded by the painting. They are ascending.

Installation shot of the big room of Rothkos at the Tate

Rothko was a surrealist before he launched into abstraction. But he wasn’t satisfied that man could “transform his cradle of imagery into a new set of images” because “different times require different images”. Indeed, he lived through a godless age that witnessed The Holocaust and the introduction of atomic bombs. This, within the creative turmoil of New York City informed the ominous qualities to his colorful mid career work that usually veiled a blinding backlight, a blood meridian.

Red predominates in the restaurant pictures and they have a Suprematist feel to them. Rothko probably saw a lot of Russian icons in his native Latvia and was familiar with Malevitch. However, he says that it was Matisse’s “Red Room” that had a big influence on his works. The formality of the canvas created a zone for Rothko to transform pure geometrical shapes with his personal worldview. Squares and rectangles hover. Their substance is atomized and the paint is ethereal. Chronologically the work evolves from multi-partite to duo-partite. We see a series done in the mid sixties where a brown square goes on a black background.

I found it hard to escape the clutches of these last paintings. We are overwhelmed by optical density and deafening light.

And then in 1968 Rothko appears to pull back from the field. His two part black and gray series has a white border. We are outside the painting now. Within, the grays swirl hauntingly. They recall moonwalk photos and I like to think that he was ready to assimilate still more “different times”.

Stefan René, on exhibit at Sacred Space Gallery, is a modern Coptic Icon painter that would leave most contemporary artists mouth’s agape. René’s art is not at the service of any earthly or personal concerns. It serves only to illustrate biblical stories and the painter’s faith in them. He doesn’t need to forge a new formal language. He thrives on the one he employs.

René’s paintings are restrained and frugal as opposed to his Russian contemporaries. He uses gold for luminosity sparingly only because “… it is expected”. The egg tempera technique is dry, sparse and earthy. These are works issuing from a 4th to 7th century A.D. Egyptian tradition founded in cities and monasteries surrounded by desert.

His reflective paintings are positioned at eye height and are but a fraction of the size of a Rothko in a Holy Book format. Although not ascending the wall themselves they contain stories of ascension.

Indeed René’s Jesus’, though calm and stony -faced, are always in motion. We never see a sleeping Jesus. He is either rising, descending or blessing. This dynamic makes him very 21st century. I see rockets tail fire and bungee chords powering the figure but never releasing him.

He is locked in Christian dogma geometry and bound by the painter’s faith, a prop in the Creator’s flux. The talented Mr. René is joyfully caught as well. The real world does creep in hence the rocket imagery for example, but Mr. René was adamant that it was a holy geometrical configuration burning at Jesus’ feet.

We are confronted with extremes. Rothko was unbound and painting to create new sense. René is bound and can’t paint outside of a given sense. Rothko created the unseen while René puts a human face on the unseen.

The dictum “Art for art’s sake” comes to mind as neither ascribes to it. Rothko’s painting embodies the self battling against hand me down meaning. This is hard, lonely work. Rothko was myth-making while René maintains myth and inherits meaning.

Rothko saw and leaves everything open to interpretation. René will see, although this reviewer would like to shake the icons free of their meaning.

Rothko put an end to more Rothkos. When René stops there will still be more icons to come.

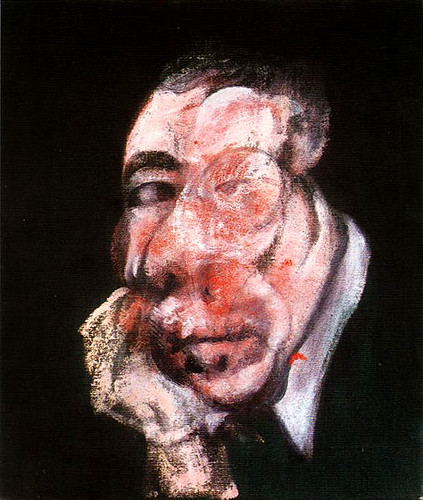

Rothko was forced to confront the limitations of his art and may just have begun painting his way back out before ending his life. René thrives on limitations. They sustain him. Addressing such extremes leaves a void in which only one artist seems to rush in to fill which is Francis Bacon.

Francis Bacon. Head III 1961, image from www.artquotes.net/masters/bacon/paint_head.htm

Bacon seems to be the just medium between the two. The partial abstraction of the figurative makes us lose a part of ourselves but we gain something in the bargain. The works have profoundly Judeo-Christian undertones. The hero is not reduced to a prop and geometry is a welcome circumscription. The field is wide open for meaning by association and we are connected to the works by the clear and heightened sense of drama.

The commission for the Four Season’s restaurant was never installed even though Rothko created thirty murals for seven possible spaces. He refused to complete the commission because he didn’t think that dining and contemplation of his work were compatible.

And of course Mr. René’s work is reminder of the strangest feast of all that is the eating of Christ’s body and the drinking of his blood.

How hard it is to get up from the table at which we sup.

–Max Mulhern, in his previous post for artblog, deconstructed the architecture of the Westfield Mall