The inimitable Louise Fishman was at the Woodmere Art Museum this past Sunday to speak to a huge crowd about her life, her paintings, her mother, Gertrude Fisher-Fishman, and her aunt, Razel Kapustin. All three artists are part of the Woodmere’s “Generations” exhibition, a powerful show about the strengths, styles, and inspirations shared among these three great, related painters.

Fishman told us that she proposed this show after realizing that her mother’s artistic reputation was in danger of suffering the same forgotten fate as her aunt’s. Razel Kapustin was at one time a vital member of the Philadelphia art world, lecturing on modernism, teaching classes at Fleisher Art Memorial, and inspiring interest in Mexican modern art; she had studied for a time with David Alfaro Siqueiros. But, as Fishman, a noted early feminist, said, “Women’s work tends to disappear.” Thus, her proposal to the Woodmere was also an attempt to find a permanent museum home for works of art by her mother and aunt.

Fishman spoke intensely and emotionally about discovering anew her aunt and mother in the process of researching this exhibition and admitted, “This is the most difficult show I’ve been engaged in.” It’s clear that her aunt Razel was crucial to Fishman’s life as a painter; she said, “Razel has my heart and always did.” Fishman described some inspirations that all three artists shared, noting several times the importance of Chaim Soutine, who “affected us all,” and with whom she feels they share “a spiritual bloodline.” Fishman wrote a paper on Soutine while in undergrad at Tyler School of Art for a class with noted art historian and founder of Tyler’s art history department, Herman Gundersheimer. She said, “I think I learned how to paint from Soutine.” Other early and lasting influences include Mondrian and Cezanne, both of whom she learned about during her undergrad years in Philadelphia in the late 1950s, and, of course, her mother and her aunt who consistently made art. Gertrude Fisher Fishman is now ninety-seven years old and only stopped painting “about four years ago.”

Fishman noted how customary the odors of her mother’s paints and turpentine were in her home life growing up in West Oak Lane and in Havertown. And even though she longed to be a basketball player, she realizes now that she had no choice in her decision to become an artist. “This show…has been very cathartic because I understand that everything was circumscribed, that this was always my path. It was in my blood, it was in my genes.” Fishman told us that she would read her Mother’s art magazines and newspapers in the bathroom and learned about Abstract Expressionism this way. She discovered Joan Mitchell, too, and this confirmed that “you could be both a woman and a painter.”

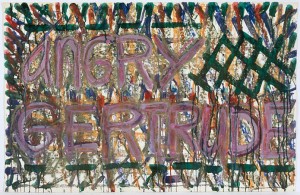

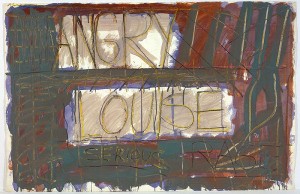

During her talk, Lousie Fishman led us to a section of the gallery in which two of her Angry Paintings hang; she described these works as “seminal” for her. Her first Angry Painting, “Angry Louise,” 1973 was made immediately after being accepted into the Whitney Biennial. Her anger surfaced, she noted, after realizing how long and how hard she had worked to achieve that recognition. She spoke about how personal these painting are to her: “I looked at it and it scared the shit out of me.” The first painting “was terribly upsetting and full of power.” She made many more, each for a specific woman who was important to her, including one for her mother and aunt: Angry Gertrude and Angry Razel. The artist described how she put herself into the body of each woman whose name appears in the paintings, and in the case of Angry Razel, she said, “I started to see the anger that Razel was not able to take on herself.” Razel Kapustin left Russia as a child and she and her family were briefly incarcerated in Hamburg before arriving in Philadelphia. “I didn’t realize what it must have been like for her,” Fishman said.

For more information on the Generations exhibition: http://www.woodmereartmuseum.org/generations.html

For more information on Louise Fishman:

http://www.cheimread.com/artists/louise-fishman/