Dear Artblog readers- Some of the artists in this show are my friends, but for the purpose of this review, I will remain as unbiased as possible.

Some people treat correspondences in the works of alumni from a particular art school like the signs of an emerging art movement. In Groupthink, curator (and Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) alumna) Lauren Gidwitz takes the opposite stance. The organizing idea behind the show is how these artists, trained in close proximity to one another at PAFA, may have influenced or been influenced by one other. Emerging strands in the show include a trend towards taxonomy and miniaturization of compositions in a way that suggests artists who stand in a peculiar relation to the classical traditions they may or may not have been taught at their beloved but somewhat old-fashioned art school. The show was held at the Pierre S. du Pont Arts Center Gallery of Tower Hill Academy in Wilmington, Delaware, which as of last year, has begun a tradition of annually hosting a PAFA alumni and student show.

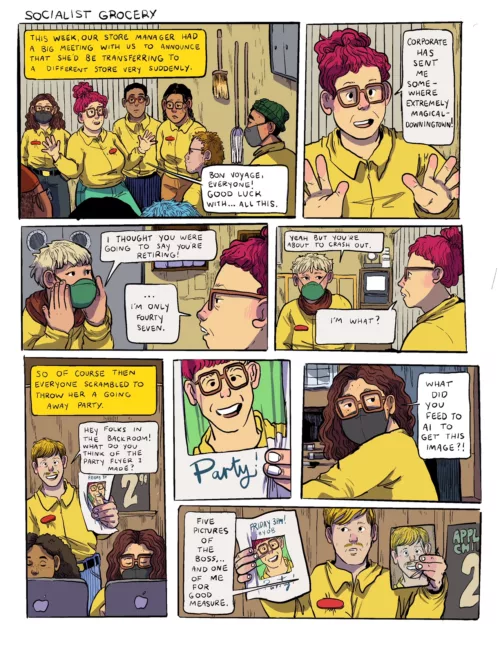

The collections and classification in this show begin with Windows of the Soul 2 by Yoni Hamburger, who usually works as a painter. The grid-portrait collects women with their eyes cut-and-pasted onto each others’ faces in alternating patterns. The creepy, some might say dead-eyed effect of mismatched eyes and faces agitates the viewer as he or she searches for what is absent – a natural unity of facial features. At the same time, it makes visually artificial faces look somehow like the norm. One feels as if Hamburger is contrasting the types of people he can classify and understand with altered versions bearing similar but different facial features. At the same time, the artificial butterflies-pinned-on-the-wall arrangement of faces feels like a type of “male gaze” that is perhaps over-enthusiastically escaping from traditional portraiture of women. Hamburger’s use of computer editing creates a technological barrier that denies the aesthetic attraction between artist and subject, as if an artist cannot be intimate with or find his subject beautiful.

Bong Mee Lee’s works are tiny collections of colors. Cup-shaped melted latex paint pieces, in Cause and Effect (above), and horizontal shreds of different painted patterns in Retreat (below), both seem like cross-sections or fragments from the process of a larger work.

Placed in orderly patterns, Lee’s works also resemble an unclear system of classifications, like miniature works that strive to represent a more traditional and complex composition. The aggregation of mixed shades of blue in Cause and Effect, presented in cup form and arranged in sequence, seems designed around portraying an entropic process, from chaotic color to form and back again.

Miniaturization also seems present in Adam Lovitz’s scattered canvases, depicting arrangements of organic shapes that play with the viewer’s sense of scale and proximity. Lovitz’s forms are heavy like De Chirico-esque classical architecture in some places, and weightless like cellular life in others. These pieces somehow seem like studies for or representations of larger paintings. In the case of smaller paintings with complex finished compositions, I often feel like I’m dealing with writers who have created “short” fiction — whether that be stories that are only a few words long like David Foster Wallace’s A Radically Condensed History of Postindustrial Life; work broken up into fragments like Fernando Pessoa’s Book of Disquiet, or the one- or two-line “10-second essay” poems of James Richardson. Compacted works on a smaller scale like these are perhaps intentionally asking for greater attention to the spare and minimal visual information presented.

Philippa Beardsley made miniaturized oil paintings even smaller than Lovitz’s, over 100 of which are in the show. These paintings are all self-contained works that together convey an indistinct harmony of color. Close-up, the style of painting varies radically from piece to piece and sometimes within each piece, from juxtapositions of figure drawing and traditional composition with broad, chaotic washes of color, to use of photography and single-hued pieces. The trends of both miniaturization and taxonomy seem present here, as Beardsley seems to be classifying and collecting small moments, emotions and thoughts in visual pieces that both indicate and represent unseen, larger ideas.

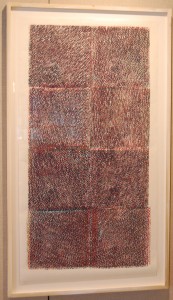

The shapes Samantha Dylan Mitchell is categorizing or collecting are so small as to evade perception. Her woodblock-print works seem like a response to the same impetus towards miniaturization as is present in other works in the show, but brought to the furthest extreme. Mitchell’s contributions to the show are two stark pillars and one smaller square piece, all with a smeared purple grid-pattern restricting and creating miniature open spaces of white. Up close these pieces resemble a frantic depiction of white noise, but from a distance shimmer quietly like sunshine on a lake. The random blurs and bleeds of the print could resemble either the bricks of a futuristic structure or a sky full of birds.

On a different end of the spectrum, traditional figurative “Academy” painting appears in a quirky form in the work of Virginia Fleming. Her oil paintings capture angles and moments of movement in the language of knees and elbows. In a grey world, her bright figures are gymnastic and vibrant. Portrayed in the midst of movement, each figure is taking off in a different direction and at times, with their limbs strewn through the other canvases. There are constantly arms and feet jutting out or into these paintings, confused faces peering out, and small pieces blanked out or missing. The confusion is strangely joyful.

Works by Matthew Herzog, Jannalyn Bailey and Jenna Buckingham in assemblage, abstraction, drawings and installations round out the show.

The show’s theme of the grid, cluster or “group” thinking is united in one wall shared by individual works from all the artists in which trends of miniaturization and the escape from traditional painting emerge. As PAFA is known for continuing to mostly teach traditional figure painting even today, some of these artists, while trying to diverge from the traditions, seem weighed down by the historical achievements of the old masters. In the dynamic directions they are working, they may yet uncover ways to expand exponentially on the lessons of the past.

Groupthink was on display at the Pierre S. du Pont Arts Center Gallery of Tower Hill Academy during the month of February. Other photos from the exhibition can be seen on Flickr.