White Petals Surround Your Yellow Heart at the ICA

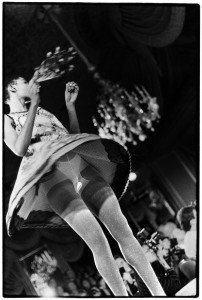

Self-adornment is surely homo sapiens’ first art form: body painting, scarification, tattooing. Garments that offer anything more than basic protection from the elements or environment can be said to participate in that tradition. White Petals Surround Your Yellow Heart at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA), University of Pennsylvania, through July 28 takes a broad, and as the title’s reference to Ovid suggests, rather poetic view of the subject. The exhibition, curated by Anthony Elms, makes no distinction between attire that was worn (RAMMΣLLZΣΣ) and clothing forms meant to be exhibited (Seth Price), between artists’ work commissioned by fashion houses (Catherine Sullivan for Steve McQueen), artists’ work that actually participated in the rag trade (Bernadette Corporation), and artwork that comments upon aspects of fashion (Zoe Leonard and Karen Kilimnick). But who cares?

On entering one is confronted by Frances Stark’s The Inchoate Incarnate: After a Drawing, Toward an Opera, but Before a Libretto Even Exists (2009), a wonderful and humorous costume that turns the wearer into a 1930s-40s style telephone. It has the antic quality of a figure from Lewis Carroll, but would make an inspired dress for Poulenc’s opera, La Voix Humaine. I missed the performance, Nine, Hour Delay, by Irena Knezevic, but the setting and props left behind create their own implicit drama: a long, pink-lit curtain on a ceiling track (of the sort used for privacy in hospitals), several circular pieces of mirrored glass on the floor, and a bunch of identical fabric shoes that are of obvious significance to the artist. They were standard footware in the former Yugoslavia (much like the black, fabric shoes from China), and Knezvic has arranged a line of them marching up the back stairs to the ICA’s ramp.

I love the group of RAMMΣLLZΣΣ ‘s fantastical masks, fashioned from still-recognizable bits and pieces acquired at hardware and dollar stores, with occasional, added polychrome. The forms largely derive from Samurai helmets, which themselves are fairly fantastical. The masks may have hidden RAMMΣLLZΣΣ ‘s visage, but his mental persona was on full and explicit view. It’s hard to imagine what visitors thought when he wore such headgear to answer the door.

‘She Builds Domes in Air’ (2012)

One of the videos Inez van Lamsweerde & Vinoodh Matadin shot for Yves St. Laurent reads as Warhol’s Blow Job with an updated hairstyle. But fashion is always cyclical, and its followers may not be expected to pick up on the recycled form, or does it pass as vintage-inspired? I had no idea that Linda Benglis had her infamous Artforum advertisement printed on tee-shirts, which she sold to finance the cost of the ad. It’s good to know she was able to leverage some of the attention it drew for her own, practical use.

The wall labels employ the sometimes-annoying habit of citing writers, from J.G. Ballard to Walter Benjamin, but Glen O’Brian’s quote, that masquerade is the intersection of life and theater which requires the willing suspension of disbelief, puts the onus of making sense of the work squarely on the viewer. Given the universality of the theme, we should all be able to rise to the occasion.

The exhibition also includes work by Hilton Als, Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, Dexter Sinister with Halmos, Leif Elggren, Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven, Erin Leland, Wardell Milan, Paulina Olowska, Nick Relph, Carissa Rodriguez, Aura Rosenberg, John Miller & Frank Lutz, Nader Sadek, Scott Treleaven, and Amy Yao.

Warrior Dash at Grizzly Grizly

Warrior Dash is a handsome exhibition of paintings by Jamison Brosseau and paintings and sculpture by JR Larson at Grizzly Grizzly through Feb. 23, 2013. According to its curator, Fran Holstrom, The title of the exhibition refers to a race in which participants are broken into categories and run a muddy obstacle course, often in costume—followed by a festival. That may be a nod to male bonding activity, but it also points to the primitivist aspect of both artists’ work. A number of Brosseau’s paintings of abstract forms on solid grounds resemble ancient ideo or pictograms of the sort that intrigued artists such as Adolph Gottlieb, Mark Rothko and Mark Tobey in the 1940s. If this evokes painting of seventy years ago it may be that, unlike so many artists today, Brosseau seems untroubled by the idea of painting. He leaves evidence of earlier phases of the compositions that belie his casual-looking paintwork, and has an interesting color sense, with an ability to use a bright, polychrome pallette without becoming overly decorative. The most complex work, Yellow Christmas Spider, has restless forms and creates a real presence.

Larson’s obvious debt to Native American blankets and tools places him in a line of American modernists from Hartley and O’Keeffe to Pollock and the Indian Space Painters. His two sculptures are particularly strong. Oculus, a large, woven head, resembles shamanic costumes from Latin America and the South Pacific. One expects it to have a raffia skirt to obscure the wearer during ritual dances. His larger piece, Double Bow, consists of a bow-like form of bent wood lashed with gut, elegantly perched on a cantilevered bench which is anchored to the floor by a large, steel plate. While the exhibition is sensitively installed in Grizzly Grizzly’s intimate gallery, Double Bow is a powerful work that I think could command a much larger space.

This is the second exhibition in a row at Grizzly Grizzly that substantially expands the range of art shown in Philadelphia’s artist-run spaces. The work has been more assured, polished and more comfortable with traditional materials than I’ve come to expect, and oddly enough, that comes off as daring. At a time when serious artists take highly divergent paths, it’s great to be able to see a broader range of work.

Catch as Catch Can at Locks Gallery

Catch as Catch Can at Locks Gallery through March 30 was curated by Fionn Meade around Francis Picabia’s painting of that title, lent by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and includes a dozen artists working in a range of media from painting and drawing to video and installation. Meade situates the work in the gap between parody and seriousness, but some of the parody requires a fair amount of insider knowledge. I preferred the work that I could appreciate without footnotes. Two large paintings by Jutta Koether read like palimpsets of the artist’s notebook and graffitied walls, pulled together by her consistent pallette and softly luscious surfaces.

Nick Mauss’s small installation, For two days I was unable to do anything, I was so stunned (2009) has an appealingly-provisional quality. A geometric, steel construction leans against a wall where it appears to support two printed images, next to a sketch on the floor, dusted with two areas of unbound pigment. Something is going on and we’ve walked into the middle of it, but Mauss lets viewers supply the story. Tom Burr’s facing rows of cinema seating suggest a claustrophobic audience and communal experience (or the audience itself as performance) that, in the age of downloaded video, is nothing but a memory. Kerstin Brätsch has hung three un-framed works made of antique glass at a right angle to the wall, allowing viewing from both sides. The glass is the support for what appear to be oversized ink drawings, my favorite of which is inset with several pieces of a different glass, whose shape looks like the lenses of spectacles.

There is also work by Will Benedict, Michaela Eichwald, Nicole Eisenman, Shahryar Nashat, Lucy Skaer, Kianja Strobert, and Viola Yesiltac.