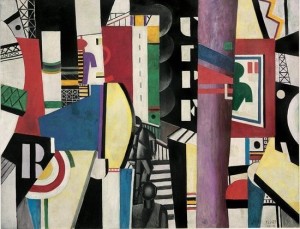

Léger, Modern Art and the Metropolis at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) through January 5, 2014, is pervaded with an optimism about industrialization and urbanization at a time, centered on the 1920s, when they were seen as the answer, not the problem, for twentieth-century society. It opens with a wall-sized projection of a film taken by Thomas Edison as he ascends the Eiffel Tower, viewing Paris through its cage of industrial steel. The artworks celebrate technologies that changed everyone’s lives, offering affordable cameras, cars, and other undreamt of commodities to the middle class. Mankind had finally realized the possibility of flight, even if airplane rides were only for the few. And cities were the locus of activity, fueled by industrial jobs and available transportation. The PMA’s installation for this fascinating and dynamic exhibition captures the spirit perfectly. The galleries suggest the new interest in unadorned, rectilinearity in architecture, and their walls are punctuated with projected films (some in their entirety, excerpts of others) that create the impression that we are looking through windows at the bustling metropolis beyond.

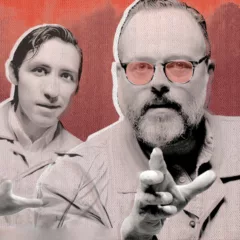

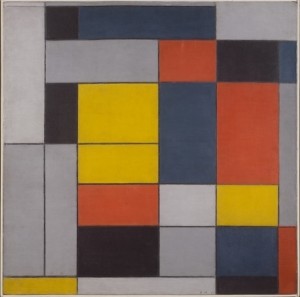

The PMA owns major works by Léger, hence the focus of the exhibition, but it is hardly monographic. It includes a wide range of work by Severini, Delaunay, Turk-Delaunay, Lissitzky, Picabia, Mondrian, Duchamp, Man Ray, and numerous others, including the rarely-seen Gerald Murphy, himself the product of an urban, commercial fortune who gave up art when he took over the family business, Mark Cross leather goods. All of them celebrated the modern, mechanical and urban, reflecting the importance of these ideas in Milan, Moscow, and Amsterdam, as well as in Paris, which for the provincial Léger, represented the ideal.

Overlapping interests and occasional collaboration of the artists

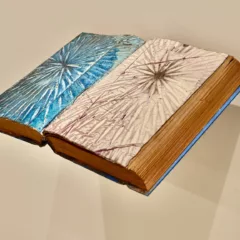

The exhibition demonstrates the overlapping interests and occasional collaboration between visual artists and those in literature, theater, dance, music and architecture. Marinetti, who created poetry from wordless sounds arranged on the page for visual effect, surrounded himself with painters. As a soundtrack for Léger’s film, Ballet Mécanique (1923-24), George Antheil composed a score for electric bells, sirens, player pianos, and airplane propellers. A ballet dancer appears in Man Ray’s Le Retour a la Raison (192)3, filmed through glass, from below, and Léger created costumes and a backdrop – spectacularly displayed – for the Swedish Ballet. Advertising and billboards were a pervasive influence of on all the arts, memorably captured by F. Scott Fitzgerald’s image of the optometrist’s sign in The Great Gatsby.

Aerodynamic aesthetics for the kitchen

Social optimists of the era predicted that mechanization would shorten the working day and relieve housework of much of its repetitive, physical labor. The style of appliances and other consumer goods is described as Machine Age. Blenders and meat slicers featured streamlined designs that had developed in response to the aerodynamic demands of airplanes and fast cars. It was also a time when art and design were thought to be integral to social progress. The Russian Constructivists believed that abstraction based on primary, geometric forms would be comprehensible to the new, Soviet masses and improve their lives.

Films of the era – motion, light and abstraction

The films, by Léger, Man Ray, Duchamp, René Clair, and a short segment of an Abel Gance film showing a close-up of pistons driving a train wheel, are essentially abstract, with no conventional narrative. Motion and light play some of the starring roles, with people, objects and geometric forms functioning as minor, supporting players. It is interesting to see how excited these early twentieth-century artists were with the possibilities of the film medium, utilizing all of its special effects: extreme angles, close-ups, double exposures, motion created by a rapid sequence of stills, trick appearances and disappearances, and the possibility of slowing, speeding and reversing motion. Léger opens Ballet Mécanique with a rather conventional scene of a pretty girl, then goes wild with a rapid collage of kaleidoscopic effects using props from the pantry: whisks, tarte tins, pan lids, wine bottles, and the like.

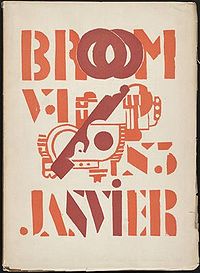

Printed ephemera and typography

Some of my favorite works are in what are considered minor media: printed ephemera and avant garde journals done on the cheap. They made free use of the forms and layout of letters on the page, transcending the convention that letters exist to create words, which convey meaning. This parallels abstraction in painting, where form was freed from representation and became the subject itself. Typography also entered the fine arts as word fragments which appear regularly in the paintings of Léger and his colleagues. They reflect the new prevalence of billboards, and the artists glamorize the disjointed, commercialized and cacophonous urban spaces which, by the 1960s, would come to be seen as in-human.

The post World War I love of the new, the fast, the commercial and the machine-made didn’t last long. Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936) is the most vivid, early statement of the distopian side of modern life. But the early, if naive, enthusiasm for modern technology produced some enduring art.

The exhibition, curated by Anna Vallye, will travel to the Museo Correr, Venice.