(Sam’s sees work inspired by crime, criminality and the grip that violence has on our imaginations in a show at Arcadia University Art Gallery.–the artblog editors)

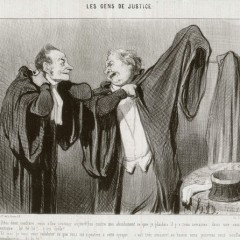

No Bingo for Felons at Arcadia University explores the parallels between artistic acts and legal transgression. Guest curated by Julian Hoeber and Alix Lambert, the exhibit includes portrayals of guns, bombs, police officers and crime scenes. With works by Honore Daumier, Yoko Ono, Zoe Strauss, and Dirk Skreber, among many others, the show takes a satirical perspective towards the legal system and forms of authority. But it is unclear whether this show ever answers it’s proposed question: “What is a crime?”

A suspicious package

Setting the tone for the show is Dirk Skreber’s Suspicious Package #2, lying unmarked in a corner of the gallery near the entrance. In the post-9/11 era, backpacks, boxes and suitcases have been branded as potential weapons of mass destruction. People can and have served prison time for making up threats about bombs or for possessing phony bombs – even comically absurd-looking objects that barely resemble bombs. One bomb threat evacuation I witnessed was caused by a repairman’s bag of tools. Recently in Fishtown, a CVS was evacuated after receiving a threatening phone call, but all the bomb squad found was a backpack full of gym clothing.

The danger associated with a suspicious package or parcel is entirely imaginary and exists only in the viewer. Skreber’s suspicious package treads the fine line of absurdity that this widespread and institutionalized paranoia represents, but if it were placed outside an art gallery – for example moved to one of Arcadia’s classrooms, or to a corner of 30th Street Station – the humor and artifice would disappear, the perceived danger would be real, and Skreber would, in fact, be a criminal.

Is it a bomb without the plutonium?

Continuing the exploration of questions about the nature of danger and the threat of violence is Gregory Green’s decidedly unsettling, non-functional 10-kiloton nuclear explosive that only lacks the plutonium needed for a detonation. Instead, a baseball sits at the center of the device. Created in 2000, Green’s piece was built based on plans he found on the internet. The bomb is dissected and left in pieces, exposed to the viewer, so that the inner workings are visible, while the entire piece can be imagined being put back together as a functional device. Everything would fit inside the red case, and if it was closed up, the package would look less suspicious than Skreber’s “suspicious package.”

A print-out in the bomb’s case that viewers can only partly see explains how the nuclear bomb would work. If detonated (by raising the temperature around the plutonium to 300 degrees Celsius), the bomb would cause total destruction to a 1,200-foot radius, and damage a 10-mile wide radius – the entire campus of Arcadia University and part of surrounding Glenside.

In this piece, Green publicly displays his knowledge of how to build a nuclear weapon, which itself might be considered a crime. It’s common knowledge that U.S. authorities track library searches, for instance on nuclear bomb technology, and few librarians have refused to cooperate with their requests for patrons’ records. Through his work, much of which explores similar territory, Green has likely put himself on the National Security Administration’s watch-list and may even have an extensive FBI file.

Forensic sculpture

Frank Bender, a Philadelphia forensic sculptor who worked for the police, made “Anna Duval” in 1977 based on the head of a dead person. The original sculpture is here, as is a photograph of it by Arne Svenson, who made a series of images of sculptures made by forensic investigators trying to identify murder victims. The functional and contingent nature of the sculptor’s task and his product leaves little room for style in this piece. The crime victim was identified as Anna Duval, allegedly killed by the mob. While portraits of the dead and even the murdered are common in art, we rarely think about the fates of the subjects we see. This piece, reflecting the death mask of a murdered woman, brings viewers uncomfortably close to the stark horrors of violent crime, even as the sculpture’s provenance, made for law enforcement purposes, reminds us of the agencies that exist to bring such acts to light.

John Lennon’s glasses and a film called Rape

Two pieces by Yoko Ono (and one by Ono and John Lennon) are included in this show – the cover of her album, “City of Glass,” which has a picture of the glasses John Lennon was wearing when he was murdered, and Rape, a 75-minute film of a film crew following a woman in public, terrifying her and chasing her. The premise of the film is that the camera crew followed a random woman chosen on the street, and gallery materials echo this, but accounts vary. According to some, the subject of the film, Eva Rhodes, who later became a model, was contracted to work in the project by her sister. According to others, Rhodes was paid for the project with a record signed by Ono and Lennon as payment and promised 25,000 pounds, which she didn’t receive for 40 years. It also seems very unlikely that the camera crew found a beautiful model by chance on the street in London. John Lennon apparently funded the movie.

Regardless of whether the crew really stalked an unwitting woman or just pretended to, the film is uncomfortable, invasive, and upsetting. The cameramen never commit a crime – they just follow the woman with a camera. But the terror she seems to feel and the damage inflicted on her psychologically seems akin to what would happen if a real crime was committed. In this exhibit, the piece seems to comment on how a non-criminal activity, such as following or tape-recording, can take on the proportion of a violent crime like rape.

The grim additional information a viewer knows about the project – Lennon’s murder by a stalker, Ono’s indifference to the subject’s personal suffering and failure to pay her for 40 years, and Rhodes’ violent death by murder in Hungary decades after the film was made – make the film feel even more like the real document of a real crime.

No Bingo for Felons can be a dark and morbid experience if you want it to be, or a a satirical romp through socially critical works that span diverse subjects, origins and sources. With art depicting crime scenes, weapons, criminal acts, victims of crime, prisons and police officers, the only thing missing from the show is depictions of criminals themselves. Then it hits you: the artists are the criminals. Rounding out the great show are anonymous photos from the collection of Luc Sante and works by Zoe Strauss, Dread Scott, Jennifer Bolande, John Divola, Vic Henderson, Suzanne Lacy, Damon Locks, Kori Newkirk and Kelly Poe.

“No Bingo for Felons” will be up through Nov. 3 at Arcadia University.