A friendly email invitation for a studio visit brought me to a peeling red door in San Francisco’s Noe Valley, the home and studio of artist William Rhodes. The trip was a little harrowing. In a rental car I had never driven, I felt like I was zooming through hyperspace. I missed the entrance to I-580 not once but twice, crossed the Bay Bridge which is always a little dicy, and then resigned myself to creep along behind a junk-man’s pickup truck so I wouldn’t miss my exit. Then I tried to park. Up a steep San Francisco stoop, the door gave no hint of the lovingly rehabbed Victorian elegance inside or the outpouring of art tumbling across the first floor studio.

Rhodes is warm, with a quick smile and a sadness in his eyes. The sadness is also in his art, as if he’s trying to capture something lost or disappearing. In our conversation about his work, we talked about religion and spirituality as well as repurposed materials.

Although raised as a Catholic, Rhodes came to question Catholicism and his relationship with God following his father’s death, which he called a “traumatic loss.” His grandmother’s small Virgin Mary presides over the mantel on which she stands. Rhodes incorporates in his work the gilding in the Catholic churches of his childhood, as well as a sort of pan-spiritual consciousness–African religions, Buddhism, and even astrology–that infuses his work and materials.

The University of the Arts alum (BA in furniture and design; MFA UMass at Dartmouth) was making wood sculptures and furniture in Baltimore for a number of years before his 2008 move to San Francisco–to a home his wife inherited from her grandparents.

Some of the substantial carved pieces in his studio, including six-foot wooden mermaid and merman cabinets with drawers and secret compartments, evoke carved wooden saints and bowsprits, the secret compartments making glancing reference to African nkisi figures. The rubbed wooden bodies bespeak the spirit in the wood. Nearby works are made of mirrors inset in vine-like wooden networks that are less about structure than about motion. The wood is all sinewy and quiet; the mirrors–which reflect like water, says Rhodes–demand attention. But move up close and the work fractures in the reflections.

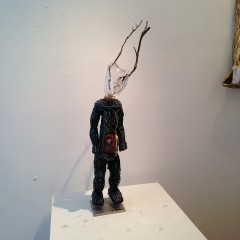

Rhodes is a preserver of family history. A small wooden figure with a compartment in its belly encases his American Indian grandmother’s tiny beaded doll. Inside the beaded doll, he said, is a small bit of animal, preserved as a talisman, maybe to embody the protective spirit of a reindeer, which was a central figure in Native American stories his grandmother told him. The figure, with its glass head and twiggy antlers, is magical.

With the cost of moving to the West Coast and rehabbing the house, Rhodes turned to making masks of the free plastic utensils from take-out meals. He writes on his web page at ArtSpan, the San Francisco equivalent of POST:

34 million tons of food waste was generated in 2010 (EPA). Second to food waste is plastic. Only 6% of all plastic waste in the US is recycled. I’ve seen this first hand while working in restaurants. The amount of food and plastic utensils thrown out every night was staggering. I chose to use plastic utensils to create art as a statement against the enormous and unsustainable waste in the US, but also as purposeful support for recycling. This artwork has allowed me to assign value to and divert potential landfill.

The masks reflect Rhodes’ travels to South America and Africa, as well as his astonishing collection of tribal art, including an ancient Dogon door, a terrific crocodile piece from Camaroon, and a wonderful crab (I think it’s a crab) from the Dominican Republic. These objects are casually displayed in the kitchen of his studio and stored in the cabinets there.

No longer using plastic utensils, Rhodes is still living light on the land. “People throw away the most amazing stuff in the city. They put out furniture, benches, chairs…” The streets provide the wood and mirrors of his current work.

My favorite of these was a tribute to an ex-San Francisco tagger HipHop Junkie. Alas, the tags stopped appearing, but Rhodes preserved HipHop in the artwork. Rhodes conjectures HipHop Junkie moved on. Maybe it was the inflated cost of real estate. “So many creative people are going to leave the city,” Rhodes said.

William Rhodes is currently in the exhibition Ashe to Amen, which documents the history of African Americans using Biblical images in their art works. The show of 50 artists, includes works by Henry Ossawa Tanner, Willie Birch, and Jacob Lawrence. Organized by New York City’s Museum of Biblical Art, it also traveled to Baltimore’s Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culture before coming to its current venue, the Dixon Gallery and Gardens in Memphis, Tenn., until January 5, 2014.

An installation of his group’s artwork from the Dare to Dream after-school program recently came down.