[Project Basho’s sponsored post introduces the photo competition juror, Andrew Moore. For more information on the competition and the Summit conference, see the Summit website. –the Artblog editors]

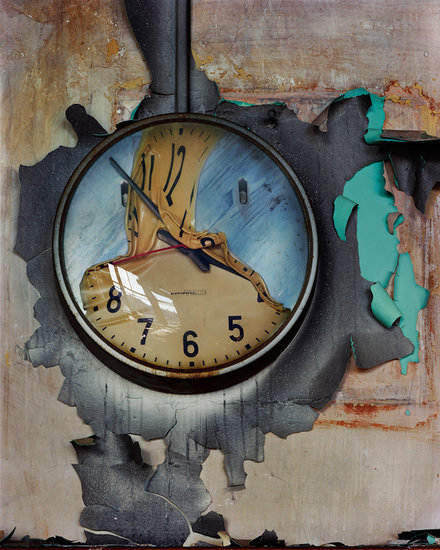

Andrew Moore is renowned for his large-scale, painterly photographs that synthesize the documentary style with the traditions of fine art into multi-layered historical narratives. In addition to his recent bestseller, Detroit Disassembled, Moore has published several books that document places in flux, including previous works Inside Havana, Governors Island, and Russia, Beyond Utopia. His photographs are in many collections, including the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Whitney Museum of American Art.

ONWARD Summit, a photography conference in Philadelphia on March 1, invites Andrew Moore to answer some questions about this year’s theme, “The Language of Place,” as well as his own work and the future of photography. For more information about the conference, please visit the ONWARD Summit site.

To coincide with the article about Andrew Moore and his lecture in Philadelphia on March 1st, we are giving away three signed copies of his “Detroit Disassembled” on the ArtBlog Facebook page. Check it out!

ONWARD: The theme of this year’s ONWARD Summit is The Language of Place: Exploring Our Surroundings Through Photography. How does your work interpret this theme? What does this mean to you?

Andrew: This year’s theme calls to mind Gertrude Stein’s famous remark about her hometown of Oakland, about which she said, “There was no there”; I have always interpreted that remark to mean that there was no defining sense of the past about that place, and no history to ground it in time. Likewise, I find that there is no sense of place in a photograph unless it alludes to time and history; that an image has to be grounded the currents of history that flow through a particular place, as well as some sense of the current moment that the photographer lives in. So, as contradictory as this may sound, what I want an image of place to display is not so much a particular geographic point on the map, but how that location has been shaped through time both by the events past as well as the present.

ONWARD: How do you attempt to bridge the gap between artist, viewer, and subject? What is your advice to a young or emerging artist for doing the same?

Andrew: I think the difference between art and entertainment is that entertainment does all the work for the viewer, while a work of art meets the viewer only halfway, and requires the viewer to use their imagination to complete the image. That’s what good picture-making is about: it’s a map that leads you through the picture plane, but also asks that the viewer actively embark on that journey. So I don’t want an image that over-describes its subject, nor do I want a picture to be composed of insubstantial clues. I think it’s hard for young artists to find that balance, between picture-making and storytelling, between design and narrative.

My advice is to find clues in the work itself, significant details that draw you into them, which ask you to follow that thread more deeply, and then not to be afraid to work and rework a particular subject or approach until one feels deeply satisfied. Sometimes I think young photographers are taken in too easily, too easily satisfied, but then it can be hard to push oneself without some kind of outside support. That’s why it’s also important to surround yourself, not only with photographer friends, but other kinds of artists, like musicians, poets, writers, and the like, who can bring an entirely different perspective to your pictures…

ONWARD: You’ve done much of your photography in foreign countries. What compelled you to travel abroad for photography? To those countries specifically? How can photography bridge gaps between cultures and trends?

Andrew: As you might have gathered, I love history and the detective-like research that goes along with it. That’s probably the reason that I started traveling and shooting so much abroad, as I loved the depth and layers of time I found in other countries, especially compared to the rather recent history of the U.S. But I was also drawn to places I wasn’t supposed to go, like Russia or Cuba, because it was illegal, or dangerous, or forbidden in some sense. Among other factors that contributed to my purpose, I was trying to bridge a gap in what I felt were Americans’ misconceptions of those places, as I felt (myself included) that many people in the U.S. had little sense of what the actual texture of life was like in those places.

But I wasn’t trying to accomplish this in a purely journalistic sense, although I do think there is a strain of that in my work, but rather as a link of the imagination between the viewer and the subject, which ideally creates a kind of opening up to the more complex realities of the place. What I especially enjoyed about photographing Cuba was that it was both exotic and familiar; that while it had many things that were outwardly familiar to someone who had grown up in the U.S., it also at the same time was a country that had very much followed a distinct and separate path from the US, so had very unique characteristics as well.

ONWARD: In a New York Times article, you stated that Detroit was the culmination of your work. Can you elaborate on that sentiment?

Andrew: I said that at the time because working in Detroit, after shooting abroad for so many years, felt like a kind of homecoming, and by that I mean there was no longer anything that felt remote or culturally incomprehensible to me, that I well understood both the broad history of the place as well as the specific detail, all the way down to candy wrappers in the garbage. All those details meant something to me in a very specific way. At this moment, I still agree with those sentiments; however, I hope that it’s not the very apex of my photography, as I’m continuing to work on new projects, which I hope will also manifest this deep connection to the subject and place…

ONWARD: What is compelling you now to stay within the United States for your current work? You’ve said before that America is becoming a harder subject to photograph. Have you found this to be true? How are you combating this?

Andrew: It’s both a loss and a gain. I have less of a fervent desire to explore places where I have so little personal and cultural connection. For example, I spent several months traveling and shooting in Vietnam, and ultimately felt quite frustrated at being so much an outsider, and at looking at things which had an extraordinary surface yet kept me at arm’s length. On the other hand, working in the U.S., I feel more connected than ever to what I’m looking at, although I have to admit that it’s hard to make something new of a country which has been so often represented. This has compelled me to work in new ways: for instance, shooting aerials, shooting with a digital back, making more portraits, and ultimately spending a great deal of time visiting and revisiting places until I get access to the kinds of places that feel unique or special to me. It’s easy to feel jaded, to feel like everything has been said and done, but if you’re attuned to history, you can see things shifting before your eyes, and so in some sense, there is always something new to be said, and the biggest challenge remains to remain in the flow of imagination, rather than stand apart and be resigned to a superficial sameness.

ONWARD: How do you select work for inclusion in a book or exhibition?

Andrew: I work in a very collaborative manner, whether in the shooting process or back in my studio. I do rely heavily on my longtime assistant, as well as friends, my gallerists, curators, editors, and fellow photographers about choosing images. On the other hand, in certain crucial decisions, one has to follow their own instincts. As, of course, a book is very different than an exhibition. There are often images in a book that would never work on a wall, and pictures that might be popular at the gallery, or that look great as a large print, that work far less well when reproduced much smaller in a book.

ONWARD: As this year’s juror, what are you looking for in a photograph?

Andrew: That might be the hardest question to answer. I admit that I have a bias toward work that is well-constructed formally, not in a rigid sense, but toward images that play with form in a way that challenges our perceptions, whether it be in the movement it creates throughout the frame, or in the ambiguous shifting of the planes of space. As a color photographer, I’m also appreciative of work where a distinctive palette is used, rather than straight up out-of-the-box local color. Actually, I think that’s one of the hardest things to explain or teach students: the way subtle color harmonies can influence not just the emotion, but also the overall integrity of the entire image. Beyond those pictorial issues, I always enjoy photographs that have a definite story to tell, especially ones that engage with this particular moment in time, that reflect on what it feels like to be alive at this very moment in history.

ONWARD: What role do you see large format photography playing now, and in the future?

Andrew: Large format is not only a craft, in that it takes one years of practice to gain a spontaneous fluidity, but it’s also a way of seeing, a discipline that helps one to completely focus on image-making in all senses of the phrase. It’s also to equal degrees both frustrating and meditative, even when one has a certain degree of mastery, yet by the same measure it’s a great antidote to the nearly reckless pace at which one can work digitally. I believe photo students should have some experience with large format, although obviously everyone is not temperamentally suited for it. The long-term problem of large format film photography is the diminishing support, not only in terms of increasingly expensive products with less variety, but also the dwindling options in terms of labs and drum scanning. So I see large format continuing to evolve in two areas; in conjunction with alternative processes, such as wet plate; and with the development of technical cameras to be used alongside digital backs. I’ve been shooting large format for more than 35 years, and still find that nothing compares to a great 8×10 negative print when it comes to large prints. But nothing stands still; we evolve, our tools evolve, our perceptions evolve alongside our culture and tools, so ideally, large format photographers will continue to use their craft and discipline in conjunction with the tools that the future presents us.