[Michael reflects on a show earlier this month that promised conflict and collaboration, and achieved more of the latter. — the Artblog editors]

New Boon(e)’s most recent group exhibition tasked a group of artists to work together to create new pieces that would unveil their conversations during the creative process–the triumphs, conflicts, and other outcomes.

Conflicts, Concessions and Convergence’s Surrealist concept was inspired by Andy Warhol’s and Jean-Michel Basquiat’s 1984 collaborative series of paintings–including Warhol’s signature brand-name subject matter and Basquiat’s crude portraiture–made with two dissimilar styles. Let’s hope that the future relationships of New Boon(e)’s collaborators unfold differently than the relationship between Warhol and Basquiat, which was permanently marred by their work together.

The playfully grotesque

Bruce Weiner and Laura Weiner simultaneously crafted two vivid ceramic sculptures, “Father & Daughter,” which are cohesive in their disembodied, grotesque anatomical imagery and color choice. Upon first glance, the sculptures’ peculiar organic forms and hierarchical display beg the viewer to see them as manifestations of a father and a daughter.

Yet the two objects feel at war with one another, as forms project and recede within a tangled web of limbs. Through tension and chaos, the Weiners find solace and exemplify collaboration devoid of contention while maintaining a sense of stylistic unity and repeated imagery.

Born out of an appreciation for the American Revolutionary War, “Seventeen Seventy Dix” by David Meyers and Nigel Hieronomous is a vicious mess of soldiers and genitalia. The painting does not take itself seriously–note the busty, skull-faced figure in a powdered wig–and is full of comical battles between liberated (i.e. nude) Americans and zombie-like British Red Coats. While the work does not accurately depict scenes from the war, it epitomizes a harmonious convergence between two artists, as the show sought to support.

Complex work sets off simple concepts

The idea that artists can collaborate on a project and work together harmoniously toward an unknown end result is very prevalent in this show. However, this notion is rejected in Anne Pagana’s and Stephanie Price’s “Manifested and It Feels So Good,” where the final installation feels meticulously preconceived and staged, like a theatrical set, suggested by the ornately festooned backdrop.

A pedestal sitting before a curtain displays the remnants of a completed ritual, including outlandish step-by-step instructions that detail how to grow a plant. The wall installation and pedestals’ use of text and aesthetic are similar, but persistently read as separate works that rely upon their physical proximity for a sense of unity.

The artists went for an ironic appeal with a peculiar title venerating the curtain and the plant–to the extent that installation could more appropriately be described as fetishizing the two. The duo exemplifies said irony to the right of the pedestal, where a pile of dried-up flower petals lie like withered flowers at a tombstone.

Contrary to the title, the revered plant’s petals have each been stained with lipstick kisses that read as tender and mournful. Subtle nuances such as these further polarize the disparity between the artwork and its energetic title.

On the farthest wall of the gallery space is “The Snugglebugs & Snugglebug Redux,” by Zac Beaver and his six year-old niece, Ella Elizabeth Jackson. Beaver yielded all decisions of imagery to his niece, who drew unprompted and developed a narrative for two bugs working in a store that sells hugs. “The Snugglebugs” is a lighthearted piece that examines the playful possibilities of collaboration when an artist concedes his or her own artistic liberties to someone else–a concept otherwise unvisited in this show.

Hidden conflict, polished results

“Corner” is a collaboration between Morgan Gilbreath and Courier Publishing Co. that looks like a mound of used eraser scraps, but in actuality, the crisp white pile is a pulverized mass of destroyed Bibles. Courier Publishing Co. shreds its flawed printed copies of the Bible; Gilbreath repurposed a batch of the once-sacred shavings and presented them in a manner that removes all references to Scripture. Once you know the story of the destroyed Bibles, the installation swells with conflict about the Good Book and its destruction and resurrection as art.

Other works, such as “Untitled,” by Christopher Joyce and Lina Pearson, provide an example where the concept of the show–but not a piece’s success–falls short. Joyce primarily works two-dimensionally, while Pearson works with fibers. As the piece developed, according to Joyce, the two encountered various obstacles, yet the final work lacks any indication of struggle.

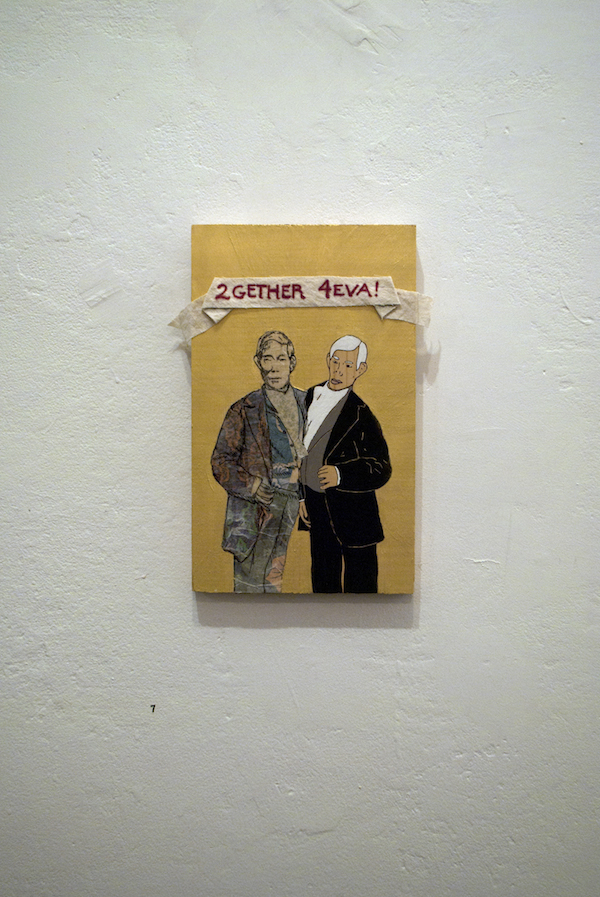

Conflicts, Concessions and Convergence is filled with successful collaborations, but the exhibition lacks artwork that truly conveys conflict. In actuality, each piece in the show appears to be a polished final work of art, like Katherine Driggs’ and Laurel Burmeister’s “2gether 4eva!”.

This is not to say that conflict was not present in the making of these works of art, but that dialogue is not visible in any of the artwork on display. Without an explanation behind the making of each work of art, the show is puzzling and seems disjointed. However, artist collective New Boon(e) takes this in stride, continuing to push for a dialogue between the artist and the viewer–revealing the good, the bad, and the ugly that ensues when artists take on collaboration.

Conflicts, Concessions and Convergence was on display at New Boon(e) on 253 N. 3rd St, Philadelphia, PA 19106 from June 6-8,, 2014.