[Natalia offers a wonderfully in-depth exploration of MoMA’s Lygia Clark retrospective, spanning from the artist’s first paintings to her later interactive installations. — the Artblog editors]

Currently on view at the Museum of Modern Art, Lygia Clark: The Abandonment of Art, 1948–1988 is the first comprehensive retrospective in North America devoted to the artistic practice of the Brazilian-born, experimental artist known for her participatory works that engage the interaction of the spectator. Divided into three distinct sections, the exhibition explores the entirety of Clark’s massive oeuvre, including her paintings, sculptures, participatory works, and installation pieces.

Leaving the confines of canvas

The artist was born in 1922 and died in 1988, and the show presents a chronological review of the many styles of Clark’s art-making through the decades she was active. The retrospective begins with Clark’s early experiments with painting. Lovers of mid-century modern design will delight in Clark’s abstract, largely black-and-white compositions that recall the likes of Piet Mondrian, Josef Albers, and Ellsworth Kelly.

As the exhibition continues, Clark’s geometric planes begin to break from the confines of the canvas, expanding onto their frames and even lifting from the walls of the gallery. This series, titled Quebra da moldura or Breaking the Frame, leads visitors neatly into the next section of the exhibition: Clark’s three-dimensional work.

Experimental “Critters”

Around 1960, Clark began experimenting with three-dimensional planes in her series Bichos, translated by the curators as “critters”. Created from opposable, hinged metal planes, the Bichos were her first pieces meant to be manipulated by the viewer. Here, the gallery is filled with Bichos of all shapes, sizes, and configurations. Additionally, several pedestals are scattered around the gallery, inviting guests to experiment with these futuristic creatures that appear to have a life of their own.

As Clark suggested, “The arrangement of metal plates determines the positions of the Bicho, which at first glance seems unlimited. When asked how many moves a Bicho can make, I reply, ‘I don’t know, you don’t know, but it knows.’” Engaging with these mercurial sculptures is both fun and frustrating–despite attempts to arrange them, the Bichos twist, pivot, and fall, apparently determined to position themselves.

Abandonment leads to interaction

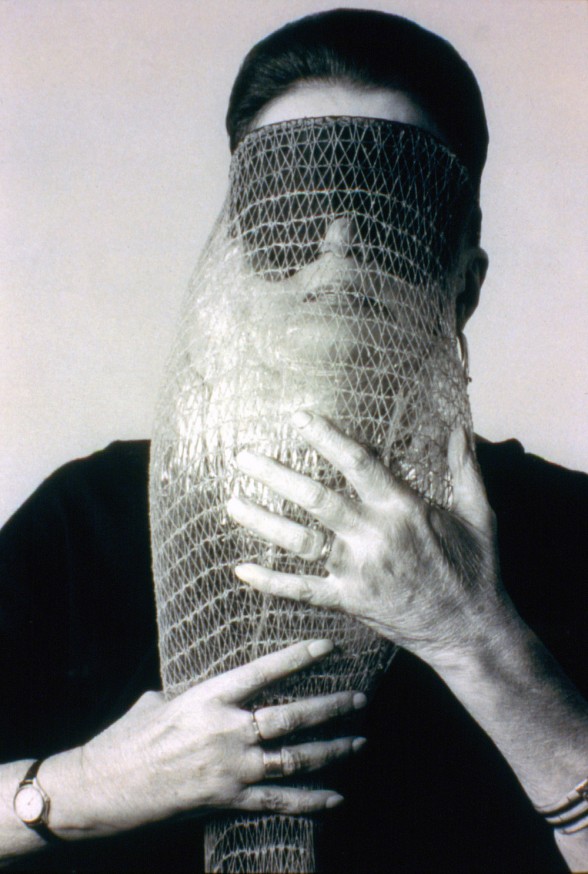

The cohesiveness of the retrospective breaks down in the final section, The Abandonment of Art, from which the exhibition draws its title. In the late ’60s and early ’70s, Clark moved away from conventional forms of art, claiming to have abandoned art-making. During this period, she created “propositions”: works that engaged the bodily participation of the viewer.

Several of these interactive pieces are included in the exhibition, including Clark’s bombastic The House Is the Body: Penetration, Ovulation, Germination, Expulsion, which can be found on the fourth floor of the museum. This enormous installation recreates the experiences of birth for participants, using materials such as Styrofoam, rubber, and balloons.

Museum facilitators will be available to help visitors experience interactive pieces at dedicated times during the week. An official schedule is available via MoMA’s website. Additionally, facilitators will demonstrate some of the more involved “propositions” spontaneously during museum hours. Unfortunately, when the participatory works are not in use, their presence in the gallery feels rather disjointed and lifeless.

Organized by Luis Pérez-Oramas, MoMA’s curator of Latin American Art, and Connie Butler, chief curator of the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, The Abandonment of Art is a thorough investigation of Lygia Clark’s oeuvre, significant and largely under-recognized in the narrative of 20th-century Modernism.

Lygia Clark: The Abandonment of Art, 1948–1988 is on view through August 24, 2014 at MoMA.