[Mary reviews a Gothic-inspired collection of works addressing feminine experience, imprisonment, and divinity versus darkness. – the Artblog editors]

Anyone able to should get up to New York to see Judith Schaechter’s exhibition Dark Matter at Claire Oliver Gallery before it closes on Oct. 25. Schaechter fully commands her conceptual and technical skills in signature stained-glass lightbox pieces and her first sculptures in kiln-cast glass. These exquisitely carved, small-scale figures create a physical intimacy and psychological vulnerability that confound our expectations of glass as rigid and unyielding. The subtle, complex surfaces of “Rest Egg” and the tortured emotion in the twisting forms of “Sleeping Girl” and “Bust” convey human resilience as well as fragility.

Creativity conquers darkness

Schaechter’s subject is the human condition, and her main artistic source continues to be the Gothic world. Stained glass epitomizes that world, in which light symbolized the Divine as opposed to the “dark matter” of humanity. Her flawed characters embody a broken world still suffused with a remnant of that light, which forms the condition of their visibility and the ground of their narrative. What begins as a metaphor for God comes to symbolize the human imagination, likewise timeless and infinite. The artist’s juxtaposition of transparent colored light and contemporary feminine experience expresses a belief in the power of creativity to mitigate the harsh realities of disappointed expectations in a world of doubt.

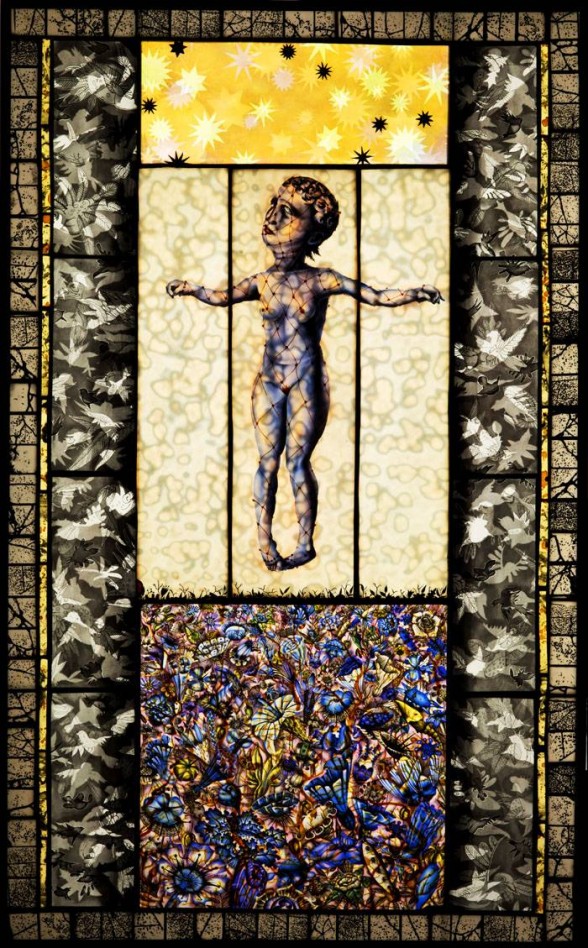

Schaecter’s works describe humanity’s desire and struggle to escape our limits of time and mortality. In “Acedia” (from Greek akedia, “listlessness”) our viewpoint moves between a frontal floating cruciform figure in a tightly cropped rectangle enclosed in a larger rectangle, and a bird’s-eye view in which the figure hovers over the smaller rectangle, now a tomb. Both readings link spiritual and mental ennui to the religious depiction of suffering and death. A comparison with Grünewald’s “Resurrection” panel from his “Isenheim Altarpiece” (1512-1516) showing Christ’s triumph over death provides a possible source for this image. The startling, bluish moonlight emanating from the empty tomb in the Grünewald mirrors the blue-tinted flowers in “Acedia,” which, though illuminated, feel cold and subterranean. The astounding yellow conjunction of natural and divine light (Sun and Son) in the “Resurrection” is suggested in “Acedia” by a small area of various yellow sunbursts above the figure, toward which she gazes with wan hope, but cannot enter. A thin red net envelops her body like a rope. She is trapped physically, spiritually, and compositionally between earth and heaven: the larger rectangle has become a prison and the edges of the tomb, the bars of her jail. The mottled, bluish figure, and the border of gray leaves and colorless birds further the feeling of diminishment.

Colorless worlds and freedom from time

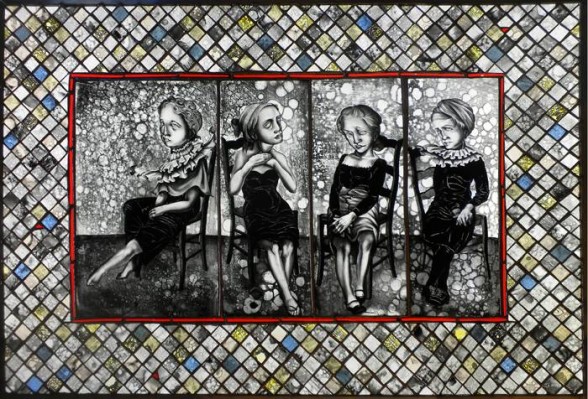

In “Waiting Room,” rectangles envelop and isolate each of the four seated figures. These women seem to be waiting for physical or moral examination–they could be in a doctor’s office or a police station–but like Beckett’s Vladimir and Estragon, they wait in vain for a Godot who never arrives. Despite their proximity, each is isolated. Boredom and disappointment characterize their demeanor. Color is absent, except for a bright red line that surrounds the four “cells,” highlighting the figures’ imprisonment. The grayish border of crossed diagonal lines suggesting a chain-link fence reinforces this theme.

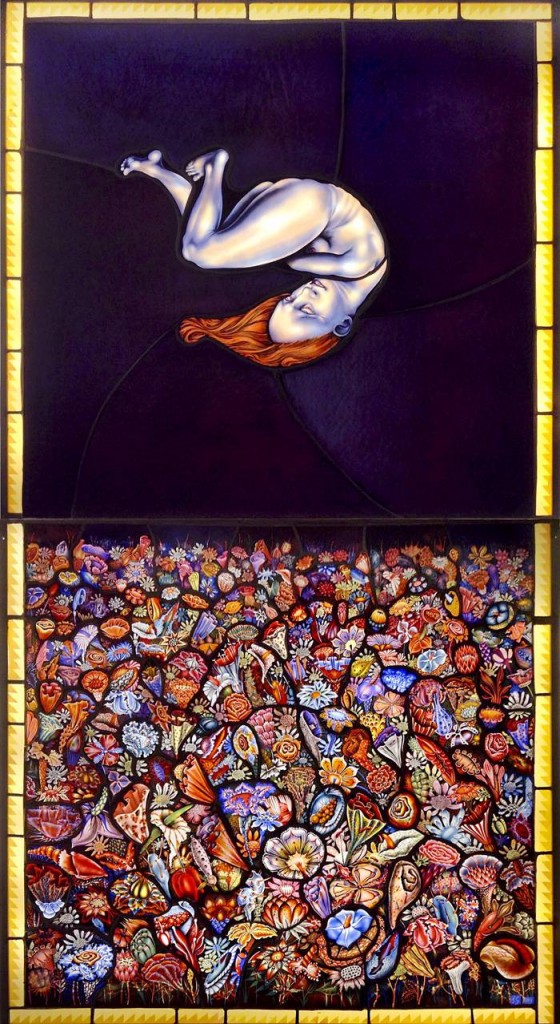

All but two of the stained-glass pieces contain women imprisoned in rectangles. In the remaining two pieces, a woman tumbles freely (“The Birth of Eve”) or floats above the world (“The New Ghost”), embodying the states before birth and after death, respectively; both are free from the constraints of chronological time (chronos). Unlike the other figures, these women have entered a moment of indeterminate time when everything happens (kairos); artists will recognize this state as creative “flow”.

Color–or its absence–helps create and support meaning in these works. For example, in “The Birth of Eve,” a pale woman is tumbling within a field of inky purple-black on top, while the bottom is filled with warm, brightly colored flowers. Set in the upper dark background and reinforcing the spin of the figure are subtle black foil lines that curve outward from the center of the space like the shutter of a camera; Eve’s curved body forms the aperture, or eye. Like Alice through the looking glass, Eve falls into the world of her imagination, symbolized on the bottom by brilliant light, saturated color, and an abundant variety of shapes. In “The New Ghost,” transparent, monochromatic blue envelops both figure and background, suggesting the realm of dreams or imagination and integrating them with infinity.

Time, epitomized by death, is inherent to the human condition. Schaecter’s vision seeks to redeem this state. Borrowing the religious iconography of light, she is able to draw a parallel between God’s transcendence and that of our imagination. Both the subject of her pieces and their strength confirm that in this world, it is creativity that releases us from our otherwise banal fate.