[Our U.K. correspondent Katie reviews a show by a pair of artists determined to shock, who are well aware of their own potential place in art history. — the Artblog editors]

Jake and Dinos Chapman have long been known as the bad boys of the Young British Artists, catapulted to notoriety by their decision to buy a set of very valuable mints of works by Goya, indisputable progenitor to their bodyshock horror-filled works, and paint their own horrifying additions onto the scenes. Now, they have brought their disturbing work to a sleepy seaside town in Sussex, the place where they grew up.

Hastings on edge

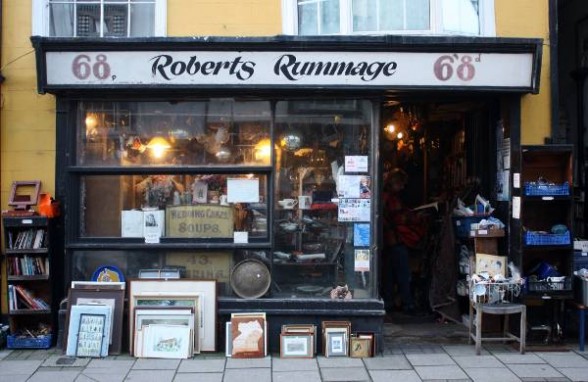

I know Hastings as a friendly, picturesque little town, all winding back streets and antiques shops and ice creams on the blowy beach. To the Chapman Brothers, however, it is “Smack-on-Sea,” a place of all of the remembered nightmares of a discontented youth, headless bodies found in the local railway tunnel, and run-ins with “derelicts” on the fishing beach. Looking out across the beach from the gallery, I spotted a van with the slogan “No Jerwood on the Stade” stickered on the side, clear evidence of the tensions between cultures in the town. Perhaps my rose-tinted memories gloss over a darker side.

Over 150 supporters contributed to a crowdfunding campaign to raise the £25,000 to put on the show. The campaign, promoted through the Art Fund website, offered specially-designed toilet rolls, temporary tattoos, and even studio visits as incentives. The strategy obviously worked–donations far exceeded the target, and the brothers are back in the town of their youth.

Imagery of absolute evil

It seems appropriate that the swath of drawings and paintings on the wall of the first room includes drawings from the brothers’ very earliest excursions into art, portraits signed in childish handwriting interspersed with contemporary work. Some of these drawings show hints of the brothers’ macabre tastes: early manifestations of the juvenile fascinations so evident in their work.

Strange, then, that Jake Chapman was in the news this year arguing that children had no place in art galleries, lacking the knowledge to properly understand the artwork. Many parents are surely hesitant to take their offspring to see the orgiastic mess of body parts, Nazis, and Ronald McDonalds that populate a Chapman Brothers show; yet their revelry in badness seems an almost overtly small-boy gesture. They delve into the explicit disgustingness that, punished and shamed in children, is eventually pushed deep underground and forgotten.

An interesting gesture was their transformation of what is usually the Children’s Gallery at the Jerwood, dropping the suspended ceiling to a height that would perfectly accommodate a child but strain the neck of any entering adult. The room is totally empty except for a painting on the opposite wall–a drab still life in shades of brown, innocuous, uninteresting, even, except for the signature: “A. Hitler”. Gore and obscenities are not the only way to shock an audience.

The constant references to Hitler, Nazism, and Ronald McDonald make for a nauseating sight. In the large, dense cabinets that make up the second incarnation of Hell, these mix together in a whirl of crucifixions and corpses with awful, many-legged mutants whose disgusting hilarity brings a fresh wave of horror. First we are sickened by the sight of so many symbols of perceived evil; then at the awful simplification our minds easily perform in lumping these icons together.

In Jake’s words, from the exhibition literature, “We use the swastika as a referent of absolute transcendental evil in the same way as we use the smiley face as a referent of absolute happiness…We’re interested in bankrupt forms. We’re interested in what these generic iconic terms have left in them.” A fast food chain does not equate to the slaughter of millions of innocent people, but the distilled imagery of both represent evil in our popular lexicon.

Defaced portraits

The show includes an exact recreation of Tracey Emin’s tent, the original of which was lost in the same warehouse fire that destroyed the original Hell in 2004. Their version is identical to the original, but the brothers title it “The Same, Only Better”. The artworks of the Chapmans and their peers, then, are also branded bankrupt forms, remembered for their bold statements, but recycled and left essentially meaningless.

Amid all of this brash self-annihilation appears a series that cuts to the heart of the Chapmans’ own careers as contemporary artists. One day you will no longer be loved (that it should come to this) is an affecting series of defacements of 19th-century portraits, painted over with awful, visceral, decaying flaws that strike at something essential, something in our instinct that knows about disease and death.

The title may taunt the viewer with their own mortality, but perhaps more interestingly, it could be interpreted as a prediction of the fate of their own creations. In an interview with VICE, Jake notes that “good portraits get into museums, but bad ones end up in junk shops with holes in them”; these works, once long-laboured-over and pronounced perfect for the pleasure of a wealthy benefactor, are now battered, neglected, and left to the whims of a couple of modern upstarts, determined to pull the legs off the culture that created them.

In the Realm of the Unmentionable is on view at Jerwood Gallery, Hastings, Rock-A-Nore Road, Hastings, East Sussex, U.K., until Jan. 7.