[Andrea digs into an engrossing exhibit that will fascinate art lovers and archaeology enthusiasts alike; she points out that the Penn Museum’s ancillary programming allows for some seriously in-depth connection with this show. — the Artblog editors]

Like the artifacts on view, many of them hidden in museum storerooms since the 1940s, the exhibition Beneath the Surface: Life, Death, and Gold in Ancient Panama at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (the Penn Museum), on view Feb. 7 – November 2015, exists on multiple levels. The collection of figured gold objects and particularly striking ceramics made by the Coclé people between 700 and 900 CE can be seen as they might be in an art museum–and appreciated for evidence of their craftsmanship and design.

A Panamanian chieftan’s grave goods

Ceramic bowls, jars, and other containers are decorated with a sophisticated use of banding–itself often embellished–that divides the surfaces into sections containing figures and patterns on a smaller scale. A number of pieces feature spiraling forms that imply movement. Some are figural, and others have a handle with a spout that Clark Erickson, one of the curators, suggested might have been used as a straw for a drink–possibly hot chocolate. The gold includes a number of plaques embossed with supernatural figures in symmetrical designs. Erickson said they represented the figures split down the middle and spread out to be seen in opposing profiles, as a chicken might be cut for roasting on a grill.

Digging deeper into the show

The second level at which the exhibition can be viewed is the archaeological. The central display contains grave goods found in an undisturbed tomb, clearly a chieftan’s, that housed three levels of bejeweled bodies. The display makes this extremely clear in a full-scale flat case with drawings of the bodies as found. The jewelry and other objects are arrayed as they were unearthed, relative to the bodies, making their functions as wristbands, headpieces, and other decorations much more real. The museum provides a great deal of didactic material in the form of wall labels, interactive computer kiosks, and projected film that is positioned at a distance from the artifacts, making it easy for visitors to pick and choose, according to their interests.

The Penn Museum is always conscious of respecting current descendants of indigenous peoples, and includes several contemporary molas–small, appliquéd cloth panels–with symmetrical designs and swirling patterns resembling those in the Coclé artifacts, although they were made by one of several current tribes in Panama and cannot scientifically be established as direct descendents of the Coclé.

One might say that these molas figure in the third level at which the exhibition can be viewed: that of the objects’ excavation and their subsequent life in the museum. It features J. Alden Mason, the archaeologist who, with many local assistants, unearthed the Coclé graves in 1940 and brought the material back to Philadelphia. A film is projected on one large wall showing rare, early color footage of the excavations. Two cases display materials related to the 1940 dig, including photographs and field notes. Some of the video kiosks offer material from a number of the archaeologists and other scholars currently studying the material. While the gold pieces in the exhibition have been displayed previously, this is the first public display of the ceramics since they were buried, at least 1,200 years ago.

Programming to support exploration

The Penn Museum, as usual, offers a range of ancillary programming, which began with a day-long opening celebration on Feb. 7 and continues with lectures, workshops, and social events. All the activities can be found on the museum website.

More unusually, the museum’s Pepper Mill Café offered Panamanian food during the first two weekends of the exhibition, Feb. 6-8 and 13-15.

Mummies up close

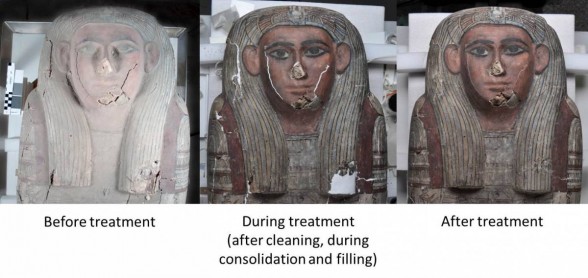

Anyone who’s never visited a conservation studio–and mummy lovers everywhere– have the opportunity to do so with a project the Penn Museum is calling “In the Artifact Lab: Conserving Egyptian Mummies”. A workspace has been set up on the third floor of the museum where visitors can look over the shoulder of a conservator working on a mummy from the museum’s collection. At specified times (weekdays, 11:15 – 11:45 am and 2:00 – 2:30 pm, and weekends, 12:30 – 1:00 pm and 3:30 – 4:00 pm), the conservation staff will be available to answer questions from the public. The project is expected to run through 2015, but it’s best to check the museum website.

There is some didactic material about mummy conservation on the walls surrounding the glassed-in workplace, and they have provided a microscope, so that visitors have the chance for a truly close-up view of specimens. At times, the conservators may be working on other museum objects that need attention because they are about to be put on view.

“In the Artifact Lab” has its own blog, which posts progress reports, research and scientific examination notes, lots of photos, and other news. Before visiting, you can see what object they are working on, and even if you can’t visit, the blog makes for interesting reading. It also has links to a fascinating array of other websites, blogs, and videos about conservation of Egyptian and other antiquities.

Beneath the Surface: Life, Death, and Gold in Ancient Panama is on display at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology from Feb. 7 – November 2015.