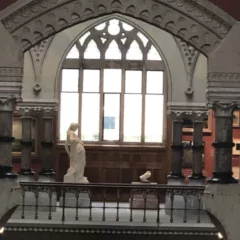

Curator, writer, and artist A.M. Weaver moderated a discussion among distinguished artists Moe Brooker, Martha Jackson Jarvis, and Charles Burwell about the position of African-American artists in Philadelphia during their student and working lives. It was held at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) on Feb. 6, and the importance of the topic was reflected in the capacity audience, which included many well-established artists, teachers, and collectors, among them Barbara Bullock, William Williams, Curlee Holton, and Judy and Louis Tanner Moore.

“Black Artists Matter” opened with two of the artists emphasizing education and the importance of mentors in their artistic lives; Brooker credited Raymond Saunders, a slightly older colleague and fellow PAFA alumnus, who told him to go to graduate school. Jackson Jarvis in turn credited Brooker, who taught Jarvis as a student at Tyler that art included scholarship as well as studio work.

The importance of community

Brooker did not mince words: “The late ’60s were dismal for black artists in Philadelphia, which is why many left.” Only one gallery would show black artists, according to Weaver, and public art commissions never went to them until the late ’70s or ’80s. Weaver said that artists here were not formally organized, as they were in Chicago and New York, but maintained connections and shared resources. She brought out the importance of community art centers such as Ile Ife, a point made again and again in the interviews conducted in connection with the recent exhibition, We Speak: Black Artists in Philadelphia, 1920s-1970s, at the Woodmere Art Museum (reviewed for Artblog on Dec. 28, 2015).

Charles Burwell spoke of the importance of a group of black Tyler students who reached into the community when he was in high school, saying it was one reason he attended the school. He also acknowledged John Wade, who set up a Saturday seminar at Tyler; Wade’s mentorship enabled black students to envision themselves becoming artists. Appreciation for generous mentors was repeated; someone brought up Martin Puryear, whose “Pavilion in the Trees” was commissioned for Fairmount Park in 1993, and the fact that he always made himself available to other artists.

The music scene also nourished the artists, and Sun Ra’s 1968 move to Germantown had a significant impact. Brooker credited music with his turn to abstraction, saying he looked to the African-American community—including the women’s hats at church—for his sources of color. He and others brought up the ongoing criticism of their saturated, polychrome palettes as “too bright” or “too garish”—or, as I heard in a comment from the room, “too colored”. Numerous artists in attendance had faced rejection based on an aesthetic rooted in the African-American community. As Naomi Nelson, director of the Underground Railroad Museum, commented in an audience discussion, things won’t change until curators of color have significant positions in museums.

Brooker’s final comments responded to the many younger artists who ask him for advice about artistic careers. It doesn’t matter whether you attend a well-known art school, he said. Just keep working.

I had returned the night before from the College Art Association annual meeting in Washington, D.C., and mentioned that scholars and artists of color received a good deal of accolade from their colleagues at the convocation, where Tania Brugera was the featured speaker. Northwestern professor Krista Thompson received the major book award for Shine: The Visual Economy of Light in African Diasporic Aesthetic Practice (reviewed for Artblog on June 18, 2015); Princeton faculty member Chika Okeke-Agulu received the criticism prize for Post-Colonial Modernism: Art and Decolonization in Twentieth-Century Nigeria; the Distinguished Feminist award went to Carrie Mae Weems; the Distinguished Artist for Lifetime Achievement award to Carmen Herrera; and Richard J. Powell of Duke University was the Distinguished Scholar honored by a special conference session. The crowd of African-American students and younger scholars who attended Powell’s session indicates that the field is rich. It’s now up to the institutions to give them a chance.