I’ve never seen so many exhibitions in venues across Dublin by artists of a conceptual bent; they address subjects from time, memory, and history to current political and economic topics. The Irish Museum of Modern Art is showing a 20-year survey, Grace Weir, 3 Different Nights, recurring (through March 28, 2016). The elegantly-installed exhibition records a good deal of the artist’s research as she investigated time, space, impermanence, and the mutability of what we accept as verifiable fact. She records time spent with astronomers who are searching for a black hole, which is recorded as a single, black pixel in the digital images recorded by the telescope; Malevich inevitably comes to mind. She also worked with physicists when she was artist-in-residence at the physics department at Trinity College, Dublin.

Both scientists and humanities scholars present details of their research methods either to back up their conclusions or interpretations, or for pedagogic purposes. It is not entirely clear to me what viewers are intended to make of Weir’s research documentation as art, despite ongoing writing on the subject. Many of the works would be incomprehensible without their backstories, particularly a series of spare explorations of the effects of time and light upon unstable pigments and dyes–what conservators call fugitive colorants.

Perhaps the most freestanding work is one of the three new videos which anchor the exhibition, the 20-minute “A Reflection on Light”. It was inspired by the painting, “Let There Be Light” (1938) by the Irish modernist, Manie Jellett, the first artist to exhibit abstract art in Dublin. The painting had been donated to Trinity’s physics department, where Jellett’s grandfather had been on the faculty. Weir’s voiceover connects the theory of relativity with the contemporaneous Cubist movement, commenting on how both were attempts to account for the variability of knowledge depending upon the position of the viewer. She also explores the interconnected disciplines and family members around Jellet, who were part of Dublin’s relatively small intellectual and artistic communities.

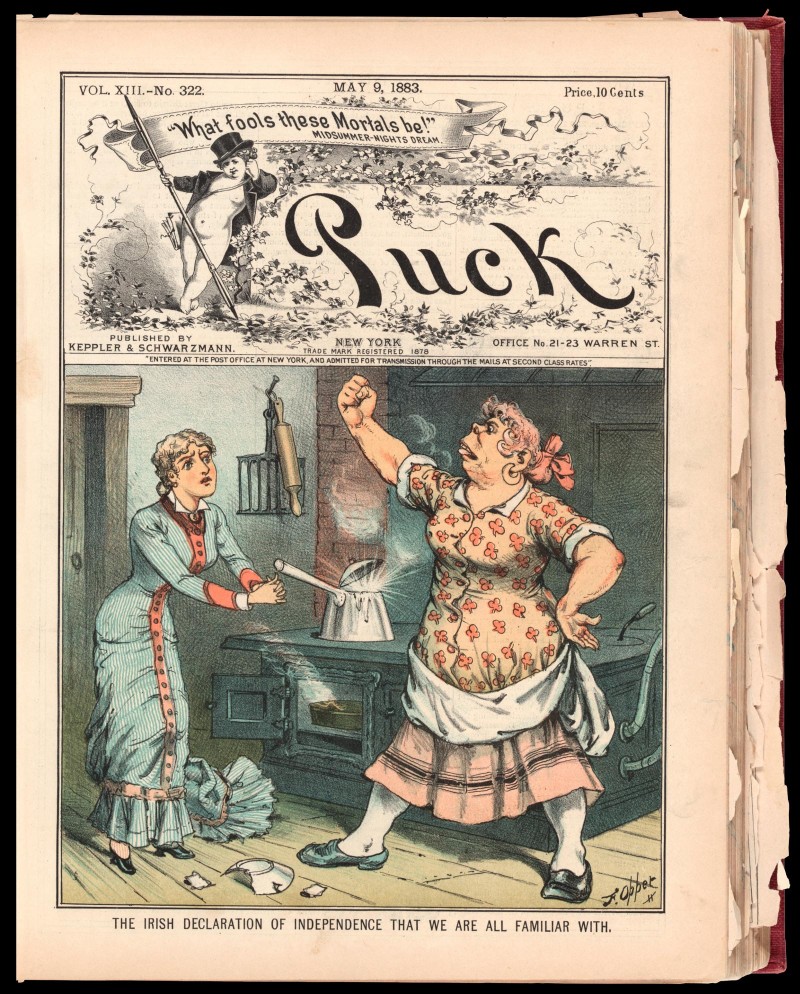

At the National Gallery of Ireland, Sara Pierce’s exhibition, Pathos of Distance grew out of a research project, Visualizing the Irish Diaspora, at the museum’s Centre for the Study of Irish Art. Pierce culled 42 images of paintings, drawings, and illustrations from magazines, newspapers, and books that depicted Irish emigrants between 1813 and 1912. She presented them as full-scale reproductions, set among three rooms of furniture, with pieces stacked one upon another and haphazardly arranged, as if awaiting proper placement.

The furniture, acquired from local dealers, represents just the sort of undistinguished and unrecorded household furnishings that might have been left behind by their middle and working-class owners. Its like never makes it into art museum collections and little enough survives to furnish the period rooms of those few institutions interested in the visual culture of the middle and lower classes–the Tenement Museum, New York; Geffrye Museum, London; and the St. Fagans National History Museum, Cardiff, come to mind.

While the images Pierce assembled show a fascinating range of individuals and events that are largely unremembered, the physical relationship of the images themselves to the furniture installations is unclear. Much of it is hung so close to the floor that I had to crouch to see it. I’m sure this was intentional, but the intent eludes me.