“International Pop,” organized by the Walker Art Center and on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) through May 15, 2016, is like an overly-rich holiday buffet, with special treats for every taste, but impossible to savor in its entirety. It’s best seen as a fascinating, if overwhelming, survey of a strain of figurative art produced from the mid 1950s through the early 1970s in Western Europe, the U.S., and a few places beyond: Japan, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Brazil, and Argentina. The exhibition does not attempt to include Pop’s greatest hits, or even the most representative work by its best known its practitioners. Nor does it display the range of scale and media that Pop encompassed–it ignores installations, fashion, and a range of printed books, posters and other ephemera. But its offerings will certainly appeal to all visitors, and abundant enticements await the most knowledgeable.

If it doesn’t provide a clear definition of what defines Pop art or why the particular international choices were made (Poland but not Russia? Argentina but not Colombia?), “International Pop” makes a highly convincing case that significant art was produced beyond those narrow regions accounted for in canonical art history. As a move towards revising that history, the exhibition is useful, even admirable. Viewers familiar with the usual short list of Pop artists (Richard Hamilton, Eduardo Paolozzi, Peter Blake, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, Roy Lichtenstein, Larry Rivers, James Rosenquist, Andy Warhol) are certain to welcome acquaintance with others, such as Tanaami Keiichi, Ushio Shinohara, Erró, Dalila Puzzovio and Antonio Manuel.

From international to local

The exhibition begins with historical factors surrounding the phenomenon of Pop: a huge, post-war increase in visual imagery in the form of illustrated newspapers and magazines–many now in color–and the new medium of television; increasing commercialism–some supported by the U.S. as a weapon in the Cold War–and an advertising industry that promoted it; and the burgeoning flow of goods and people across boundaries, enabled by airplanes and cheaper transportation. The labels acknowledge–but I think under-emphasize–the influence of youth culture in the phenomenon of Pop. The overwhelming majority of works on view were made by artists in their twenties or early thirties. Large numbers of artists that young had never garnered international attention before.

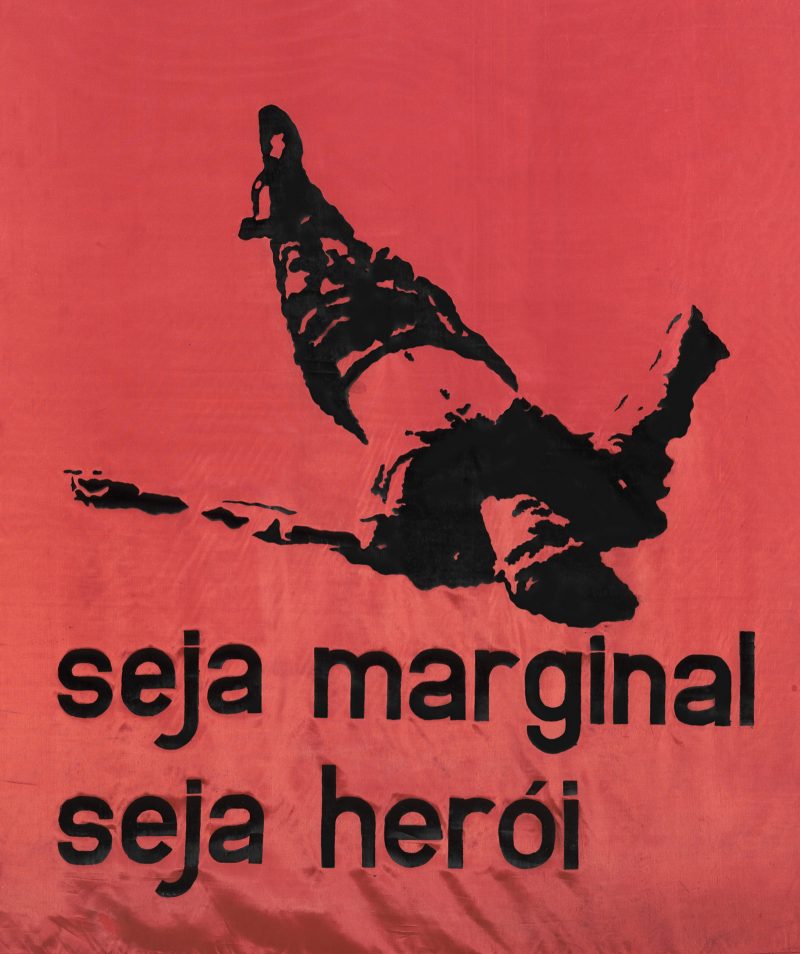

The curators address the fraught nature of the times, marked by the Vietnam War, Cuban Missile crisis, U.S.-backed military rule in Latin America, activism on behalf of civil rights, and early feminist activity. They were concerned with identifying formal, material, and conceptual connections across boundaries, despite the obviously varying and often extremely local conditions in which the art was produced. And perhaps this last is one of the most significant points the exhibition makes: despite an international interest in the commercial vernacular and the visual impact of the media, the works in the exhibition can only be truly understood within the cultures that produced them. This leaves serious viewers with the realization that the information in many of the introductory labels is insufficient background for a real understanding of the art and how it functioned in its native territory.

Halfway through the exhibition is the billboard-sized “Foodscape” (1964) by Erró, an Icelandic artist working in Paris. It’s a wall-paper-like array of packaged and prepared food, only a step beyond the fluorescent-lit landscapes of American supermarkets and the optimistic abundance promoted by advertising–but in 1964, supermarkets were unknown beyond the U.S.; shoppers still went from the neighborhood greengrocer to the butcher and baker, or to weekend markets. The American obsession with more of everything must have seemed like an impossible dream to viewers in Eastern Europe and other poor countries, and a vulgarity to most Europeans.

Expanding the canon

Antonio Manuel’s “Repressao outra vez–Eis o saldo (Repression Again–Here is the Consequence)” (1968), consists of five black hangings that, when lifted like blinds by the viewer, reveal news photos of violent state repression of citizenry in Brazil. It implicates the viewer in the continuing state violence, and reminds us that interactive needn’t involve computers. The section of the exhibition displaying Japanese work includes wonderful, short animated films that are projected above the hanging artworks. Two by Tanaami Keiichi involve a humorous transformation of advertising and soft-core Western porn; this is equivalent to European artists in the late 19th century who used Japanese prints–which were commercial, popular images, some of them erotic–as an inspiration for high art.

When looking to expand the art historical narrative beyond the U.S. and Western Europe, the curators found artists who in many cases were politically oppositional–but they ignored similar artists in their own back yard. Some American examples include Betye Saar and Noah Purifoy, who employed vernacular objects, John Outterbridge, who made assemblages of commercial detritus, David Hammons, Faith Ringgold, and May Stevens, who used the American flag and the visual language of advertising, Martha Rosler, who made collages of magazine and news photos, and Hannah Wilke, who toyed with media representations of women. All are thematically and conceptually closer to the idea of Pop explored in the exhibition than artists such as Christo, Bruce Conner, Jasper Johns, or Paul Thek–none of whom would have considered their work Pop, but who are nonetheless included in “International Pop.” This suggests that there is a lot of work left to do on revising the canon, and this exhibition is a welcome step along the way.

A program of Pop films was organized to complement the exhibition, mostly screened at International House.