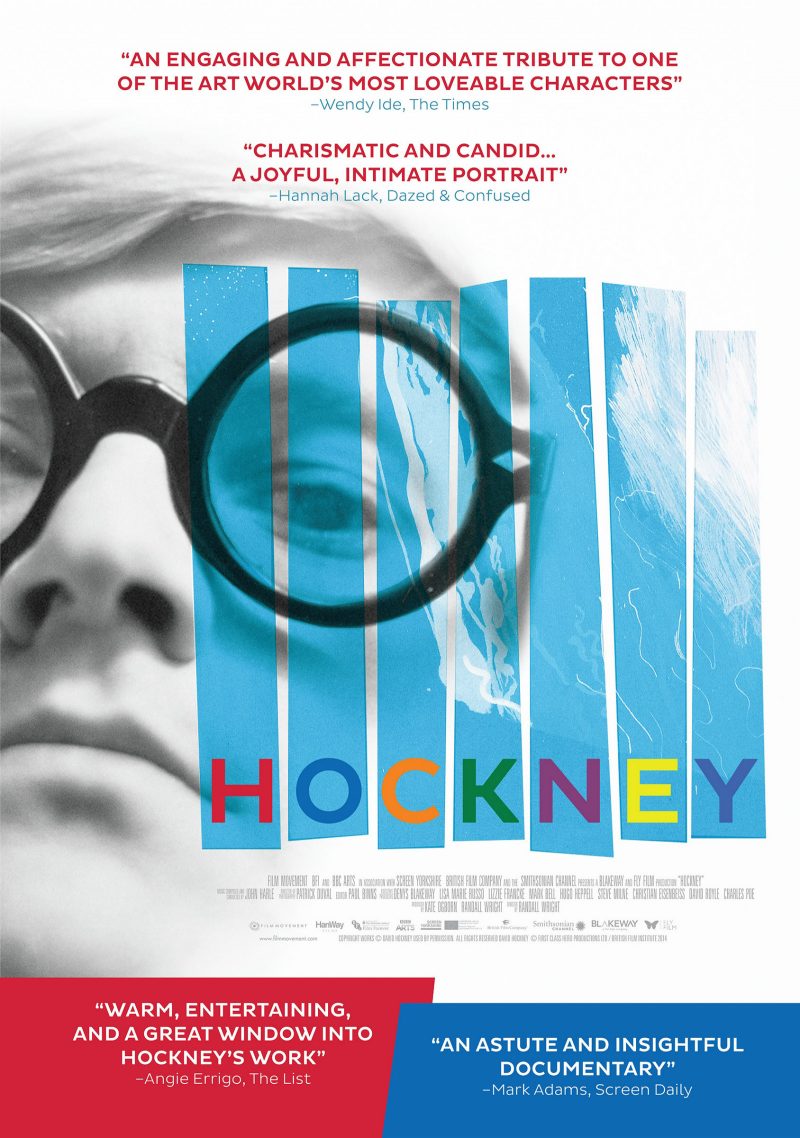

Director Randall Wright’s gentle documentary “Hockney” takes an amiable, at times elegiac look at the British artist David Hockney’s life and work. Through a series of interviews with people close to Hockney, as well as archival footage taken throughout the artist’s long and productive career, Wright’s film feels like an impressionistic visual diary. This documentary is decidedly not an introduction to the artist, age 78, or an analysis of his significance in twentieth-century art. We hear the voices of friends and family, not critics and historians, but White gives over a great deal of screen time to the work itself, which allows viewers to form their own opinions and reflect on the sheer beauty and technical skill of Hockney’s art. As a long-time fan of his work who is less acquainted with the details of his life, I found the film engaging, if occasionally frustrating. Given the importance of Hockney’s relationships with friends and family, I would have liked to have more context for the people interviewed over the course of the film, whose names only appear briefly on the screen.

A Yorkshire aesthete

The film opens with Hockney’s childhood in Bradford, in West Yorkshire, and the artist recounts two of his earliest and most vivid memories of his parents. During the Blitz (the German bombing of England during WW2), his mother took her children down into the basement. When a bomb fell on their street, she screamed–a sound that he remembers to this day. His father, Hockney recounts, was able to paint a perfectly straight line along the handlebar of his son’s bicycle. Watching him, Hockney says, was like watching Michelangelo paint a circle. In this simple but telling anecdote, Hockney conveys a sense of domestic intimacy as well as art-historical awareness, making his father at once a working man and an artist.

Raymond Foye, one of the more detached critical voices in the film, observes that Hockney is rather like a nineteenth-century aesthete, carefully cultivating his eccentricities. Mark Berger, Hockney’s classmate at the Royal College of Art in London, recalls that the young artist used to have a five-foot-tall turquoise teddy bear in the middle of his bed, much like Sebastian Flyte in Evelyn Waugh’s novel, Brideshead Revisited (1945). But Hockney is far more than a caricature of a dandy.

“Things as they are”

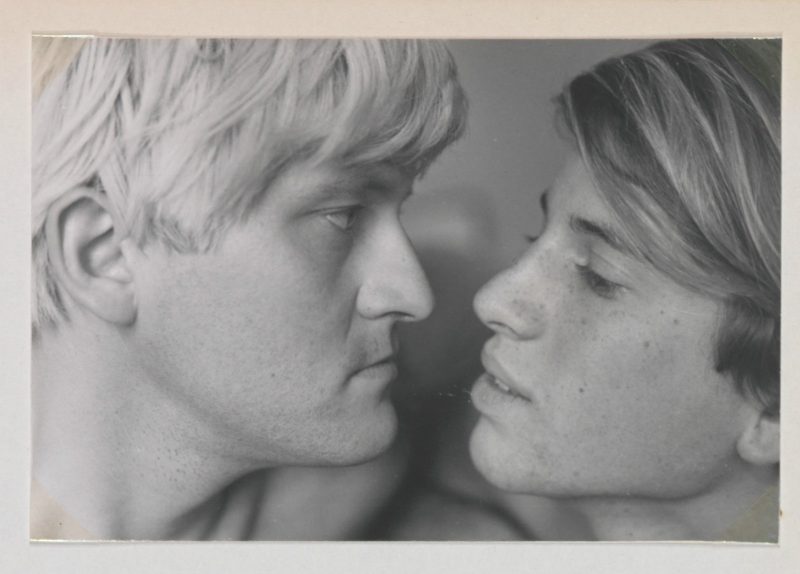

Some of the most compelling sequences in Wright’s documentary consist of the artist’s reflections on perception, perspective, and space. After a painful breakup with his longtime partner, Peter Schlesinger, Hockney made a series of etchings based on Wallace Steven’s poem, “The Man With the Blue Guitar,” which was in turn based on Pablo Picasso’s famous 1903-04 Blue-period painting, “The Old Guitarist.” Hockney was drawn to the poet’s insistence on “things exactly as they are,” using his etchings to play with realistic and illusionistic depictions of space, all within the emotional frame of the artist’s life and relationships with others.

Hockney’s close relationship with family and friends, many of whom appear in the film, is an important theme throughout the documentary. We are encouraged to see his paintings as explorations of the space between people, of distance and proximity both emotional and physical. Although Hockney is known for being an openly gay artist, the delicacy and even reticence with which he explores sexual themes make his paintings, as one friend put it, “not just pictures of men fucking.”

Vanishing points

Towards the end of the film, Hockney talks about the need for new perspectives, for a depiction of space that takes into account our behavior within it. In his most recent series of landscapes, “Yosemite Suite,” Hockney paints Yosemite National Park with his iPad. His landscapes invite viewers to insert themselves within the scene. He attempts to reverse the logic of classical perspective, making us, the viewers, his vanishing point, widening out and opening up the picture to us, rather than retreating to a distant point within the composition.

The film returns to Yorkshire for its conclusion, and we revisit those close family ties with which we began. Hockney’s mother passed away in 1999 at the age of 99, having lived through the entire twentieth century. I wish I had a clearer sense of the personalities of his family members, especially his mother, who is the subject of an incredible 1985 portrait that is shown only briefly, but which suggests volumes about her personality. Alert, piercing blue eyes gaze out, as if seeing “things exactly as they are.”

The film ends with a sequence in which Hockney leads us silently through his California home, moving outside down colorful painted stairs to a perfectly blue swimming pool. He is alone in his paradise, a bittersweet coda for a man and an artist who thrives on human relationships.

“Hockney” is showing at the Ritz at the Bourse through Thursday, 26 May.