Mierle Laderman Ukeles is a visionary whose work over the past 45 years has enlarged both the form and content of the art of our time. While revered among artists interested in feminism, performance art, social practice, and institutional critique, and a significant influence on two younger generations of artists, many of whom may not recognize her name, her work has not achieved the broad renown it deserves until now. All the more congratulations are due to the Queens Museum for organizing “Mierle Laderman Ukeles: Maintenance Art,” on view through Feb. 19, 2017. Organized by Queens Museum curator Larissa Harris and Patricia C. Phillips, Chief Academic Officer/Academic Dean at Moore College of Art, it is the first survey of her work and its catalog is the first comprehensive monograph on this groundbreaking artist. Ukeles is extremely well served by both. The exhibition not only documents the artist’s work in both an engaging and detailed manner; it also reveals something that has eluded the printed record of her work, until now the primary means by which I and many others have known it–that is, its visual and aesthetic sophistication and power.

Motherhood and maintenance

In 1969 Ukeles was a young artist and the mother of a baby. She was overwhelmed by the amount of repetitive, unacknowledged labor involved in caring for an infant and dismayed that she was no longer seen as an artist, but as a mother who made art. She decided that the only way she could continue to be an artist and keep up with the unending, monotonous activities of child care was to consider those daily chores to be her art. In one sitting she wrote the Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969, the first highly visible statement of feminist art practice, which includes the memorable line “The sourball of every revolution: after the revolution, who’s going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?” The subject–not cleaning or garbage, but human systems which involve the most universal and basic of human functions–would define her career. In January, 1971, Jack Burnham included part of the Manifesto in an article in Artforum, along with four photographs of Ukeles’ Maintenance Art showing the artist dusting a baffle, rinsing a B.M. diaper in the toilet, cleaning a chicken foot, and dusting an artwork.

At its beginnings, Maintenance Art involved the artist chronicling her daily household activities. When six museums responded to a letter from the artist offering to do Maintenance Art at their facilities, she had a stamp made to certify those activities as “Maintenance Art,” with room for a date–a practice she continues to this day. She incorporated a form of validation traditionally used in the art trade for activities performed entirely outside the system of commerce and collecting. When the Whitney Museum’s downtown branch invited her to be part of an exhibition, Ukeles conceived of a project that involved the 350 maintenance workers of the office building in which the museum was sited. This was the first of the large-scale collaborative works that have marked her career.

Ukeles and the sanmen

In 1977, when New York City was in dire financial straights and considered declaring bankruptcy, Ukeles wrote the city’s Commissioner of Sanitation, proposing that she become an artist-in-residence at the Sanitation Department (DSNY). When the commissioner responded positively, she began a project that in various forms has become her life’s work. Its best-known components are the performance, “Touch Sanitation,” and the ongoing planning to convert the world’s largest waste dump, Fresh Kills Landfill on Staten Island, into a public park. Her association with the DSNY has continued for forty years. The department has provided the artist an office and cooperation, but she has never been paid. Her residency at DSNY has encompassed the span of Ukeles’ intellectual and artistic concerns, from a feminist approach to maintenance labor, to interest in the problems of urban waste, to concern for the ecological future of the planet.

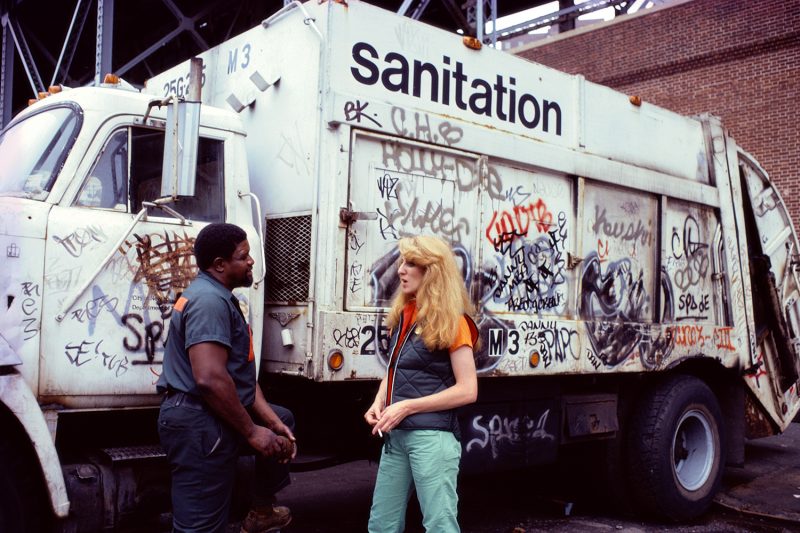

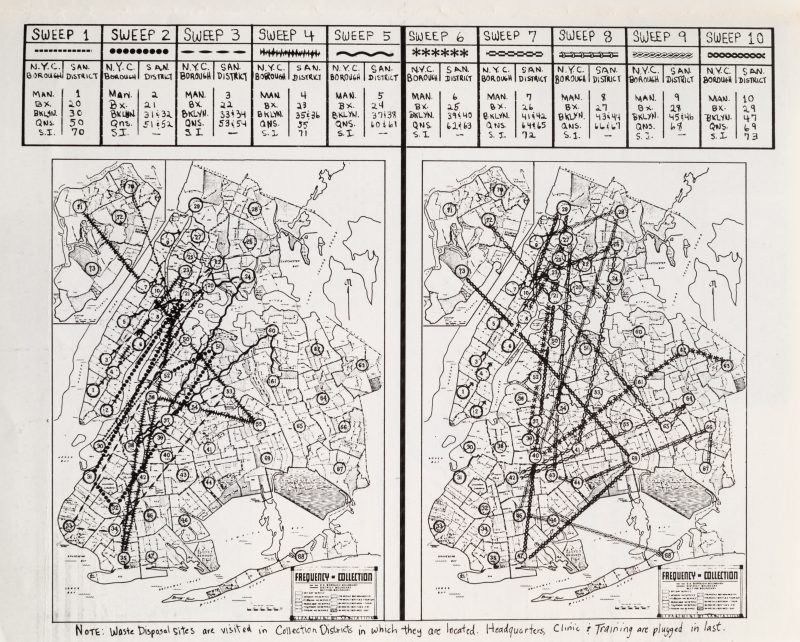

All of Ukeles’ work is based upon extensive research. She spent an entire year studying the DSNY’s activities before writing the letter in which she proposed her performance, “Touch Sanitation.” She asked the 8,500 sanmen–the term preferred by the workers–to participate in the project, which involved her shaking each one’s hand and thanking him for keeping the city alive. For most of them it was the first time any member of the public acknowledged their importance to the city; they were more accustomed to nasty epithets. The Queens Museum has made inspired use of its most unusual resource, the giant panorama of New York City constructed for the 1964 World’s Fair, to trace with lights Ukeles’ route for “Touch Sanitation”–making the scale of her performance palpable–and the atmosphere is animated with sound recordings made during the project.

Ukeles’ work has required great diplomatic, bureaucratic, and logistical skills in addition to voluminous research. But her ultimate success is undoubtedly due to her sincere modesty. She let all the staff she met, during her residency at DSNY and on all other projects, know that they were the experts about their work and she was there to learn. She’s a good listener. Ukeles has done numerous other projects with DSNY, including mirroring all sides of a sanitation pickup truck to participate in an art parade, so the viewers might realize that the garbage is theirs, devising a ballet of mechanical sweepers–which inspired requests from agencies around the world for similar projects, which are shown on videos in the exhibition–and convincing DSNY supervisors and city officials in suits to follow the parade with brooms, as the sanmen regularly do.

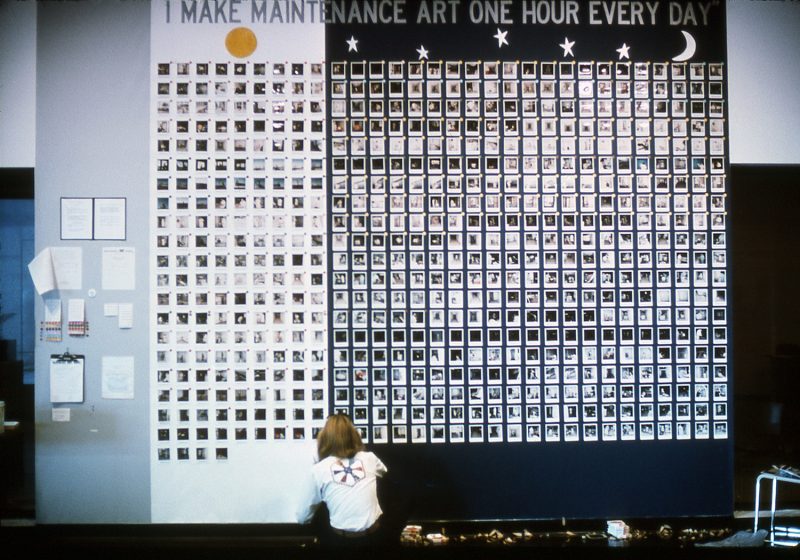

Ukeles celebrated “Touch Sanitation” with two concurrent exhibitions, both requested by many sanmen she talked with. One was at the 65,000 square foot Sanitation Department transfer station, which the artist turned into a spectacular installation of mechanical and hand tools, equipment, and protective clothing used by the department along with indications of the variety of the garbage they handle; visitors were also treated to a barge ballet on the Hudson by vessels used for conveying material to landfill sites. The other exhibition was at Ronald Feldman Gallery, where visitors could climb a platform and participate in wiping clean the front window which had been entirely obscured by graffiti-ed insults the sanmen had received.

The reparation of the world

Ukeles’ art is built upon a foundation that is the last taboo of serious contemporary art: religious beliefs within a mainstream, Western faith. The topic embarrasses critics and historians who have only discussed Ukeles’ Orthodox Judaism in reference to two projects where it is part of the subject–a work about the Jewish ritual bath, or mikvah, and a collaborative project based upon Tikkun olam, or reparation of the world. But her religion is more than a theme for two projects; it is the basis of her view of life and hence, art. Ukeles has been comfortable acknowledging this; she cited the Talmud–a compendium of rabbinic interpretations of biblical law–in her initial letter to the sanmen, requesting their participation in “Touch Sanitation.” Judaism makes no distinction between the sacred and the secular; all of life is covered by religious law, codified in the Halakhah. It addresses what to eat–and what not to–marital relations, business conduct ,and the treatment of animals. Jewish law also prescribes behavior that causes no harm to others and helps those in need. The idea that all the activities that sustain us are worthy subjects of art is a reflection of the Jewish concept that a religious life involves every action we take. Mierle Ukeles’ career is an extraordinary example of a life and career built upon religious ideals.

The exhibition is well worth the significant effort it takes to get to the Queens Museum, and is a must-see for activist artists and others interested in the most challenging forms that art has taken over the past half century, and one of its pioneers.