“The Freedom Principle; Experiments in art and music from 1965 to Now,” organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago occupies both floors of the Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania (ICA) through March 19, 2017. The unconventional, dynamic, and music-filled exhibition has two parts; the first documents an extremely fertile period, from the mid sixties to mid-seventies, when a community of black artists and musicians in South Chicago formed a number of artists’ organizations–the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), dedicated to experimental jazz, the Organization of Black American Culture Visual Artists Workshop (OBAC), and the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists (AfriCOBRA)–and created community venues jointly as a means of developing and presenting their art. The artists and musicians were each other’s first audience and a number of participants straddled both sectors. Chicago was highly segregated at the time, and musicians and artists shared the goal of creating positive images and examples within the larger, political vision of black empowerment. All of it was directed at their own community.

The second part of the exhibition, which brackets the first at both beginning and end, traces the legacy of the artists, and more importantly the musicians, in contemporary work by David Hammons, Stan Douglas, Terry Adkins, Renée Green, William Pope.L, Charles Gaines and others. “The Freedom Principle” was organized around themes of collectivity, experimentation and improvisation by MCA curators Naomi Beckwith and Dieter Roelstraete.

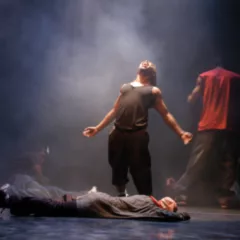

Anthony Elms, chief curator at the ICA, has organized a parallel project, “Endless Shout,” a series of performances, lectures, panels and other events over the six-month run of the exhibition, chosen by six musicians, dancers, and visual artists: Raul de Nieves, Danielle Goldman, George Lewis, Taisha Paggett, the Otolith Group and Fred Moten. Its stated goal is to ask “how, why, and where performance and improvisation can take place inside a museum,” and “offers improvisation and collectivity beyond music or dance, imagining these techniques as structures for social organizing in public and civic space.” While the verbiage sounds like something written for a grant proposal, the program promises a broad range of very interesting events.

Elusive traces

“The Freedom Principle” shares the challenge of many documentary exhibitions: much of the visual art from the 60s-70s was either ephemeral or has not survived. The music fares somewhat better in that it always reached a significant part of its audience through recordings, which are available. The one, monumental visual artwork that came out of the scene, “The Great Wall of Respect”–painted in 1967 on a building torn down in 1971–was an unauthorized mural, collaboratively produced by OBAC members on a 60-foot long, exterior wall of an abandoned neighborhood building; it received national attention even during its execution (a good source for photographs and information on “The Great Wall” is a website sponsored by the Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University). The mural depicted black heroes, whose names were sourced from the community; the figures changed as the mural was completed and then altered, but it always prominently included a group of jazz musicians. “The Great Wall” inspired similar murals in minority neighborhoods around the country, sometimes calling on the expertise of the Chicago artists. Unfortunately, the surviving photographic documentation of “The Great Wall” must not have been suitable for a life-size reproduction within the exhibition.

One of the major paintings on view, “Jam Pact/JelliTite (for Jamilla)” (1988) by Jeff Donaldson, one of the mural’s initiators, gives some idea of the vibrancy of the music scene as represented by the artists: pulsating, brightly-colored patterns and waves of tessellation surround recognizable details of the musicians and their instruments. Wadsworth Jarrell’s portrait of Angela Davis, “Revolutionary,” (1972), originally a painting which also circulated as a screen print, has a similar quality of almost electric energy and theatrical lighting, with words radiating in patterns around Davis’ signature Afro hairstyle. “The Freedom Principle” also includes paintings, collages, screen prints, drawings, sculpture and clothing by Muhal Richard Abrams, Ayé Aton, Emilio Cruz, Jae Jarrell, Barbara Jones-Hogu, Roscoe Mitchell, Nelson Stevens, Gerald Williams and Jose Williams and documentary photography by Robert Abbott Sengstacke, Lauren Deutsch, and others.

Visual music

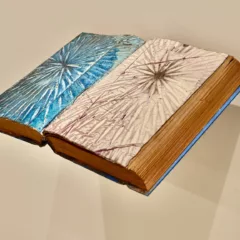

Some of the musicians produced visual work in the form of unconventional scores of great calligraphic inventiveness and complexity; the exhibition includes numerous scores by Anthony Braxton, as well as examples by Wadada Leo Smith. Much of the visual art reflects a graphic sensibility, which I suspect was a planned effect of work intended to circulate as screen prints, posters, flyers, concert programs, record jackets, and printed ephemera. “The Freedom Principle” includes a broad range of such material, much of it documenting or announcing performances and musical events by the Art Ensemble of Chicago and other AACM musicians, as well as extensive photographic documentation.

George Lewis has noted a common aesthetic among musicians and artists of assemblage technique and its associated contingency, heterogeneity, and non-linearity which was manifest as collage by the artists, and in the use of found objects as instruments by the musicians. The AfriCOBRA artists codified an aesthetic stance; that alone set them apart from most artists of the period. A statement of 1973 specified free symmetry based on syncopated, rhythmic repetition, the maintenance of figuration at the compositional center where it meets non-figurative elements, clarity of form, luminosity–or “shine”–and bright colors. All agreed that their art would be dedicated to positive racial consciousness and political equity. This last, an instrumental vision of art, was widely at odds with the art being shown in mainstream art museums and galleries.

Contemporary resonances

The contemporary work in “The Freedom Principle” adds considerable heft to the exhibition, partially because much of it is large scale and lives up to those ambitions. The entrance is filled with the music that undergirds the exhibition, in the form of Stan Douglas’ “Hors-champs” (1992), a double-sided video projection edited from a recording made in Paris of a musical foursome with two original AACM members, Douglas R. Ewart and George Lewis. At the rear of the first floor and in contrast to the cozy, carpeted space of Douglas’ video, a considerably larger, high-ceilinged gallery holds an installation by Lewis and Ewart working with Douglas Repetto. “Rio Negro II'” (2007/15) is a garden-like environment of rain sticks, chimes, and various low-tech instruments and structures made of bamboo which make sounds in response to mechanically driven movements. The rain sticks come from indigenous Brazilian rituals, reflecting a range of antecedents broader than the Afrocentrism of the 60s-70s.

Over the past couple of decades, almost all American art museums have claimed a mission to reach out to “underserved communities,” yet none of them have acknowledged that these communities have their own well-developed aesthetics of art and material culture. They differ from the mainstream, and the institutions have not been willing to embrace aesthetic values beyond their own. The first part of “The Freedom Principle” is remarkable for doing just that: exhibiting art–and music–that was selected by a group of artists largely excluded from the mainstream of their period, who developed a different set of aesthetic aspirations and standards.

In 1971, four of the Southside artists were invited by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago to participate in “Murals for the People,” where they were to produce murals in the museum, with the public looking on, which would be distributed across the city. According to Donaldson, “Because the muralists feared being co-opted by such a mainstream museum environment, they prepared a manifesto declaring the public’s ownership of the walls created by the mural movement.” They also insisted that Southside community residents were offered free museum admission.

Fifty years later the educational and art institutions have changed. A few of the AfriCOBRA artists had formal art education, while the musicians had less, but almost all the contemporary artists shown here have MFAs from major art schools, and most of the artists organizing “Endless Shout” hold professorships at mainstream universities–George Lewis is Edwin H. Case Professor of American Music at Columbia University. They have become part of the mainstream establishment–by which I do not mean that racial exclusion is not still a significant factor in American society, or even within academe. But it does mean that they no longer make art for entirely black audiences in segregated communities in which they live. Money also plays a part that was absent for the earlier artists. Many of the contemporary artists are represented by major, international galleries, which indicates the prices charged and hence, their audiences. If any of them fear being co-opted, they’ve been quiet about it.

The politics of aesthetic choices are raised in a monologue in “Afterword via Fantasia” (2015), a large, video installation by Catherine Sullivan with George Lewis, Charles Gaines and Sean Griffin. Sullivan’s compelling but non-linear video relates to a larger project, an opera by Lewis titled “Afterword.” The video sites groups of actors reciting text from Lewis’ opera within Chicago stage sets for George Gershwin’s “Porgy and Bess,” Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot,” August Wilson’s “Two Trains Running,” and Regina Taylor’s “Stop, Reset,” all of which address themes with parallel social concerns to “Afterword.” The monologue to which I refer comes from the epilogue to Lewis’ definitive, scholarly book about the AACM. It raises the question of what it means for black artists to incorporate aesthetic devices from mainstream culture; will they thereby lose some of their own, distinctive aesthetic identity? And will they be able to retain black audiences?

This reminds me of debates by artists during the nationalist excitement of 20th-century post-colonial and post-Soviet states, who were called on to forge new, national art styles. Would they base them upon indigenous motifs and methods, as one way of rejecting the colonial past–or on ideas derived from international modernism, which in the mid 20th century largely meant abstraction, as a means to indicate their parity with other nations? While many of us would consider all artistic decisions to have a political basis, whether stated or not, debates around politics and aesthetics in the U.S. today rarely seem as urgent as they did to the artists here.