Paint the Revolution: Mexican Modernism 1910-1959, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through Jan. 8, 2017, charts the complex story of two generations of artists in Mexico who attempted to redefine both modernity and Mexicanidad–Mexican-ness–in light of war prompted by peasant revolt and subsequent political upheavals. The huge exhibition is hard to follow even for viewers familiar with the material. As with almost all attempts to forge a national style to represent a new regime or nation, the art politics of the time are rarely transparent to outsiders; the multi-authored exhibition catalog is very helpful here. But the art is highly varied, passionate, and raises issues of continuing relevance.

Varieties of Modernism

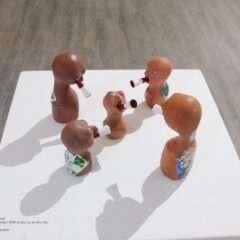

The exhibition has work to please almost every taste. There are paintings that reflect ideas from Impressionism, Symbolism, Expressionism, still lives by Cézanne and Picasso, Robert Delaunay’s city scenes, Bakst’s designs for the ballet, pan-European interest in folk art, social realism and Surrealism–across topics from portraiture to urban and rural landscapes to images of war. It includes photography that runs the gamut from engaged ethnography and reportage to Constructivist abstraction, and mural cycles that re-invent a tradition of grand, narrative painting cycles that reaches back to European art of the 14th to 17th centuries. The handful of three-dimensional works are particularly striking: several small carvings by Mardonio Magaña–a laborer who learned to sculpt in middle age at one of the state-sponsored Open Air Painting Schools, and two extraordinary masks by Germán Cueto, which interpret a traditional Mexican popular form in the language of advanced art. There is also an impressive range of graphic work, from caricatures to small-circulation magazines and books designed for intellectual circles to the products of the socially committed artists of the Taller de Gráfica Popular–People’s Graphic Workshop.

The exhibition clearly demonstrates that the widely-known work of Rivera, Orozco, Siqueiros, Tamayo, and, in recent decades, Frida Kahlo, is but a small spectrum of a much broader artistic scene. It brings up topics such as the tension between work intended for private viewing versus the obviously propagandistic intent of work meant to be seen in public–both murals and inexpensive prints; the Mexican response to European modernism; European, Soviet, and U.S. responses to Mexican art; the tension between a cosmopolitan artistic language which reflects international ideas about modernity versus a local style that draws upon indigenous art, and with that, the ongoing attention in Mexican art to the spectrum of racial difference. The one modernist concept that found little place within the Mexican artistic scene, other than in photography, was abstraction, which was central to Soviet revolutionary art, although rejected soon after by the Soviet regime.

Monumental statements

Mexican art of the revolutionary period is best known for the many state-sponsored murals commissioned for public buildings. Most were done in fresco–dried pigments painted on wet plaster with which they fuse as the plaster dries–they become part of the walls, literally site-specific. It was the standard European technique for wall painting before the sixteenth century, and was one of a number of early techniques that intrigued artists in the nineteenth century. Frescoes are integral to their walls, as well as too large to travel. A few Mexican artists cannily painted some portable murals when they realized the international interest; other frescoes have been removed from their walls. But most are represented in the exhibition by excellent, digital reproductions, some of which approach true scale.

Several Mexican modernists infused their choice of techniques with an importance unusual elsewhere. David Alfaro Siqueiros famously thought a modern art should employ modern materials, and turned to the commercial enamels that had been developed for industrial purposes, such as appliances and cars; he also sometimes applied paint using a commercial spray gun. There is no more dramatic 20th century representation of the horrors of war and ethnic cleansing than his “Collective Suicide” (1936), which shows the native population throwing itself off the edge of a mesa rather than face the much better-equipped Spanish Conquistadores. Siqueiros produced an inflamed atmosphere with his use of swirling patterns that can be created with enamels. Jackson Pollock learned about enamel paints when studying with Siqueiros in New York, and it has been suggested that the scale of the muralists’ work influenced the turn to large canvases by the Abstract Expressionists.

Race and class

Frida Kahlo, on the other hand, turned to local traditions for her materials as well as her format. Two of her five paintings in the exhibition, “Self-Portrait on the Border Line Between Mexico and the United States” (1932) and “Two Nudes in the Forest (The Earth Itself)” (1939), are among the group of self-portraits she painted in the format of Mexican retablos–or devotional paintings, which she collected–that also use the retablos technique of oil on a metal panel. Since Frida always emphasized her mestizaje ancestry–both European and indigenous Mexican–her fusion of European and Mexican colonial art traditions reinforced her message.

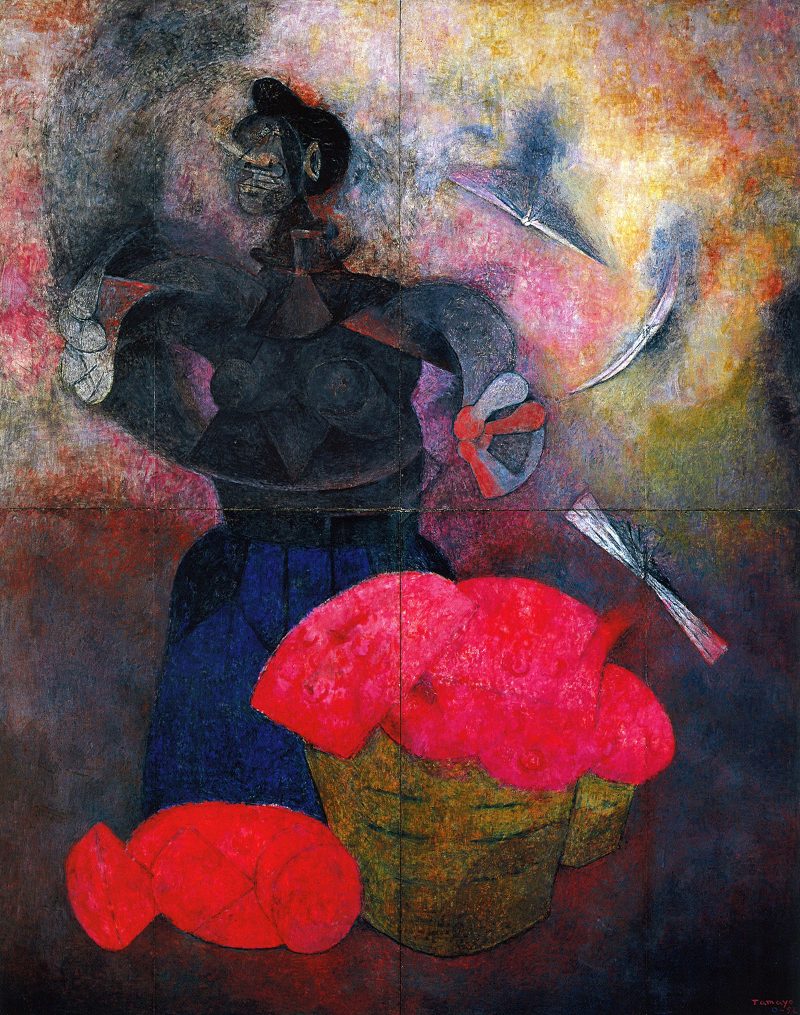

Rufino Tamayo is alone of the better-known Mexican artists in his avoidance of explicit political references in his work. But his jumble of sign-painters barely visible within the cacophony of competing messages in “Corset Advertisement” (1934) reveals his understanding of the power of visual propaganda, albeit of the commercial sort, and its prominence in the urban environment.

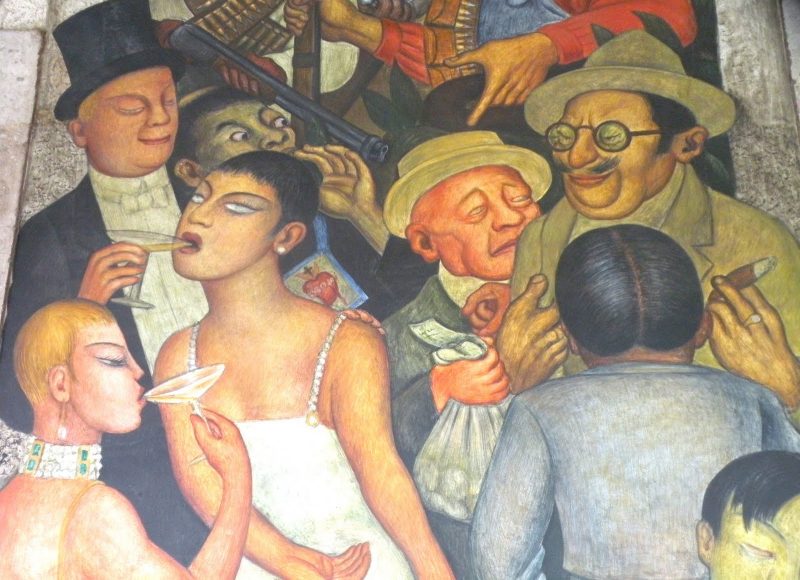

The Spanish colonies in the New World were all marked by a good deal of intermarriage among the colonizers, the indigenous population and often the descendants of enslaved Africans. This does not mean an ideal of a racial melting-pot; quite the contrary. The distinctions of racial mixture were calibrated with considerably finer grades than in North America, and its hierarchy pervaded social, economic, and political life in Mexico; the gradations of color were categorized by a genre of 18th-century Mexican paintings called castas. The post-Revolutionary demand for a national art, which for one group of artists meant an art that acknowledged indigenous visual traditions, ran into conflict with the social realities of the indigenous population, which was largely rural and illiterate. Those artists who looked to Mexican traditions drew almost exclusively from historical and archaeological art and architecture, rather than the visual culture of their contemporaries. The scenes of modern life depicted by muralists and easel painters alike indicated the continuing racial hierarchies–at one end, the obvious descendants of the local population, distinguished by both facial features and skin color, then a variety of mixed-race people with European features and a spectrum of skin colors. Diego Rivera paints the disdained, former bourgeois overlords as blonde and of pale complexion, while José Clemente Orozco depicts a blond, European God displacing the Aztec god, Quetzalcoatl.

Paint the Revolution continues at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through January 8. Open Tuesday through Sunday, 10–5 pm (Wednesday and Friday open until 8:45 pm).