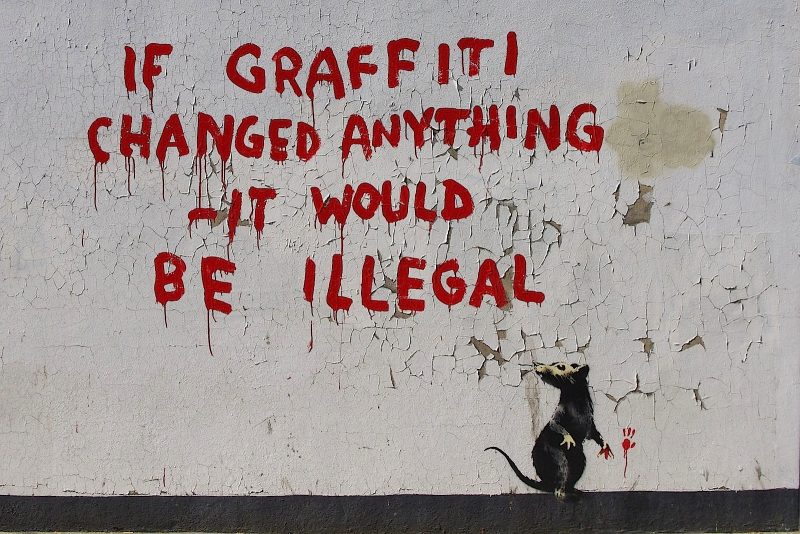

“If graffiti changed anything, it would be illegal.” – Banksy

Art is not a gun. It is not a policy, a government, or even a single idea. At its best, art is a seduction of the senses, a cultural signpost, a complicated set of philosophies that can beg questions, tell stories, and reflect this world with all its warts and blemishes. But can art function politically, persuade the body politic, and call people to action?

Culture workers have been working overtime ferreting out the differences between art and politics ever since Trump World officially launched in November of 2016. The January 21 Women’s March flooded Washington D.C. with hundreds of thousands of protesters on Trump’s first full day as president–double the inauguration count. Replicated across the country, and cities and towns across the planet (including those on an Antarctic exploration voyage), women (and men and children) marched with handmade signs of resistance in an unorchestrated group performance piece, a contagious grassroots political expression that hadn’t been seen in the U.S. since Vietnam.

The arts of resistance

Small actions and objects became symbols of resistance–hand-knitted “pink pussy” hats became the de facto signifier of defiance. These homespun craft works by ordinary citizens signaled a rising, transcendent power in the sea of protest of Trump and the right wing politics that has taken over the country.

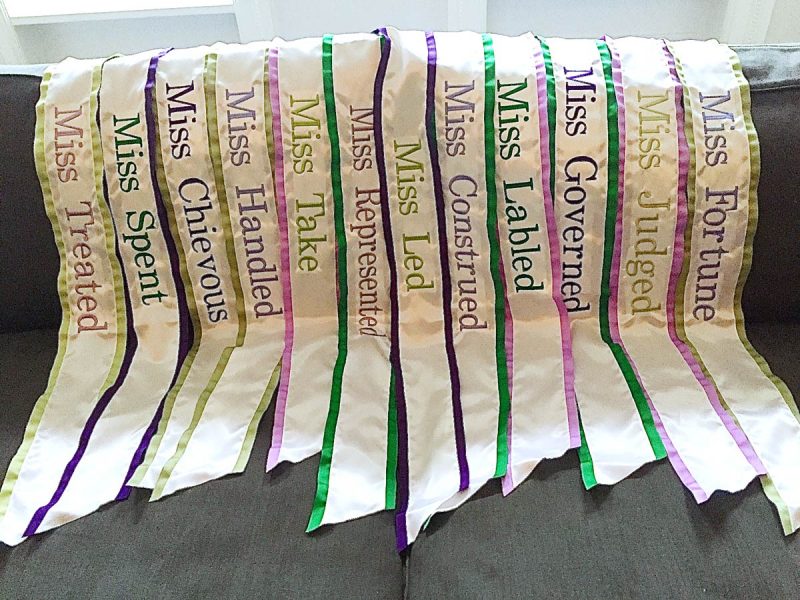

In Brooklyn, New York, a small group of women artists, curators, gallery owners, and printmakers called the Victory Garden Women’s Collective came together to print and distribute more than one thousand “Suffragette Sashes” for the January 21 marches. The pieces echoed the women’s suffrage march in Washington D.C., March 3, 1913. Designed by artist Louise Eastman, some of the dozen sashes read, “Miss Treated,” “Miss Judged,” Miss Handled,” and “Miss Led.”

“The political value of such mass demonstrations cannot be underestimated,” says Walter Robinson, the New York painter, former editor for Art in America, and founding editor of Artnet and one of the founders of Printed Matter. “We know now–especially in the wake of the triumph of the deeply dishonest Trump campaign–that protest art can both carry the progressive message and forge unity among demonstrators and help keep their spirits high.”

But clever slogans, hashtag activism and messaging is not art as we might recognize it; the term “political art” might in fact be more misleading than edifying because graphics and slogans hail from the realm of drive-by politics–bumper stickers, flyers, and wall posters–more propaganda than art. But art can be anything now in our post-post-modern, leaderless art world. So who is to say #Black Lives Matter is not art?

“I think it’s fair to say that political work made by artists is informed by a particular ideology, but to call it propaganda is either a misuse or a misunderstanding of the term,” says Paddy Johnson, editor of the online art magazine Art F City.

Johnson makes the argument that artists are not political operatives, though some do advocate for specific policies. “Just because art exists within a political system doesn’t mean that it is, in fact political.”

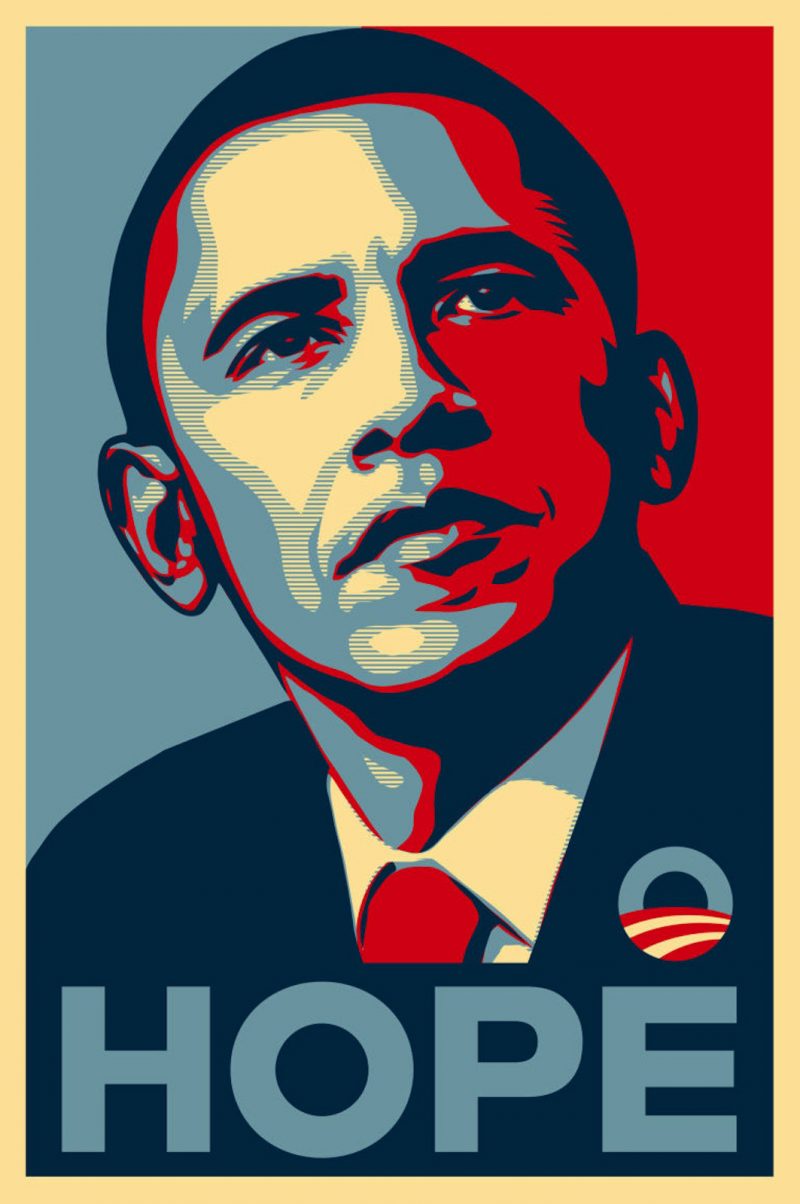

In 2008, the Obama “HOPE” poster by artist Shepard Fairey rapidly ascended to iconic stature and became the go-to message for then-candidate Barack Obama. Did it help Obama win the White House? After Obama’s election, Fairey’s work was mired in a legal thicket largely about copyright, though the poster was acquired by the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. At the same time Fairey’s Obama was copied and reproduced by the millions–some in satire, some in tribute–for a variety of purposes. There is a great truth about effective art that touches upon politics and social justice. It strikes deeply and its impact is often immediate (as with Fairey’s Obama). Though, of course, the message might not last long; the DNA of the body politic, I fear, often gets bored and at its worst, complacent.

Representation and power

Great art about political and social injustice (Leon Golub comes to mind), political uprisings and their aftermaths (Manet’s “The Execution of Emperor Maximilian” or Goya’s “The Third of May, 1808”) often resonates in ways formalist and abstract works do not. There is patriotic art you might see on engraved onto stamps or coins or the presidents chiseled into Mount Rushmore. The Soviet Union gave birth to Socialist Realism–great art works that adorned currency and schools, but is now viewed as kitsch.

Picasso’s “Guernica” and Calder’s “Mercury Fountain” were clearly meant to bring awareness in a less connected world to the war crimes that devastated the Basque town and the toxic mercury mined in Spain. “Guernica” portrayed the horrors of the Luftwaffe’s intentional bombing of civilians, and was displayed along Calder’s work at the 1937 International Exposition in Paris. The works raised consciousness but did little to stop World War II and the devastation to come.

In the run-up to the 2016 election, a young artist named Illma Gore created Make America Great Again, a pastel portrait of a nude Trump with a tiny penis, lampooning the Republican candidate who made an issue out of his sexual prowess. The work drew immense media attention and got the artist beaten up. Gore’s work was one of thousands of caricatures and portraits of a politician many women reviled. The piece is now on view in London’s Maddox Gallery. Whether the work and all the social media frenzy about it had any real impact on the culture is improbable. More likely it was a passing titillation, although it helped the artist achieve overnight notoriety.

In a different political critique, David Wojnarowicz, the late painter, musician, filmmaker, and AIDS activist once sewed his mouth shut (Untitled, 1990, by David Wojnarowicz) in the Rosa von Praunheim’s extraordinary 1990 “Silence = Death.” What is significant is that Wojnarowicz created this work as AIDS ravaged America and the world. His and others’ actions yielded tremendous awareness–all helped by conservative opposition, literally fueling the controversy about federal support for combating AIDS. Eventually, the government came around to helping contain the AIDS epidemic. Wojnarowicz, though, was just one of hundreds of arts who helped to change policies in government. While such art activism is slow to achieve results, art of all forms and flavors that pushes forward a message does open the door to the national town hall’s slate of political discussions.

Taking on Trump World

Dissident political messaging comes in many forms. Institutions, too, have played a role–The Museum of Modern Art even put together an exhibition of Muslim artists just two weeks ago in response to Trump’s “Muslim Ban.” Other museums and art spaces sought to create a day of silence called the #J20 Art Strike, which encouraged museums to shut down on 20 January; it had varied results and little lasting impact.

After Trump’s legally dubious “Muslim Ban” in January, the respected lefty-liberal and pro-art and culture magazine, The New Yorker, ran a cover of John W. Tomac’s “Liberty’s Flameout”–the Statue of Liberty’s bright torch of welcome in New York Harbor now a lingering wisp of smoke drifting off into darkness.

Since the election, artists and voters seem more engaged and emboldened than ever; while approximately 40 percent of the electorate did not turn out to vote, something is happening, perhaps an awakening, observes Robinson. “The popular protests against the unconstitutional calumnies of the Republican Trump regime have opened an entirely new dimension of political art,” he says. “Both in the proliferation of anti-Trump memes on social media and the inventive designs for signs used in popular mass demonstrations, the graphic arts take center stage with witty and pointed messages couched in contagious forms that communicate exceptionally well.”

Saying “No,” canceling exhibitions, and shutting down projects are what some artists are doing in protest to Trump’s administration and policies. Conceptual environmental artist Christo scrapped his 36-mile curtain over the Arkansas River in Colorado because Trump is the new landlord of the public waterway, he said. Richard Prince, the more than controversial artist who often appropriates other artists’ works, suddenly found religion and returned $36,000 for an “Instagram” artwork he made of First Daughter and contemporary art collector Ivanka Trump–though it’s hard to tell if Prince returned the money in a ploy for attention or an actual protest.

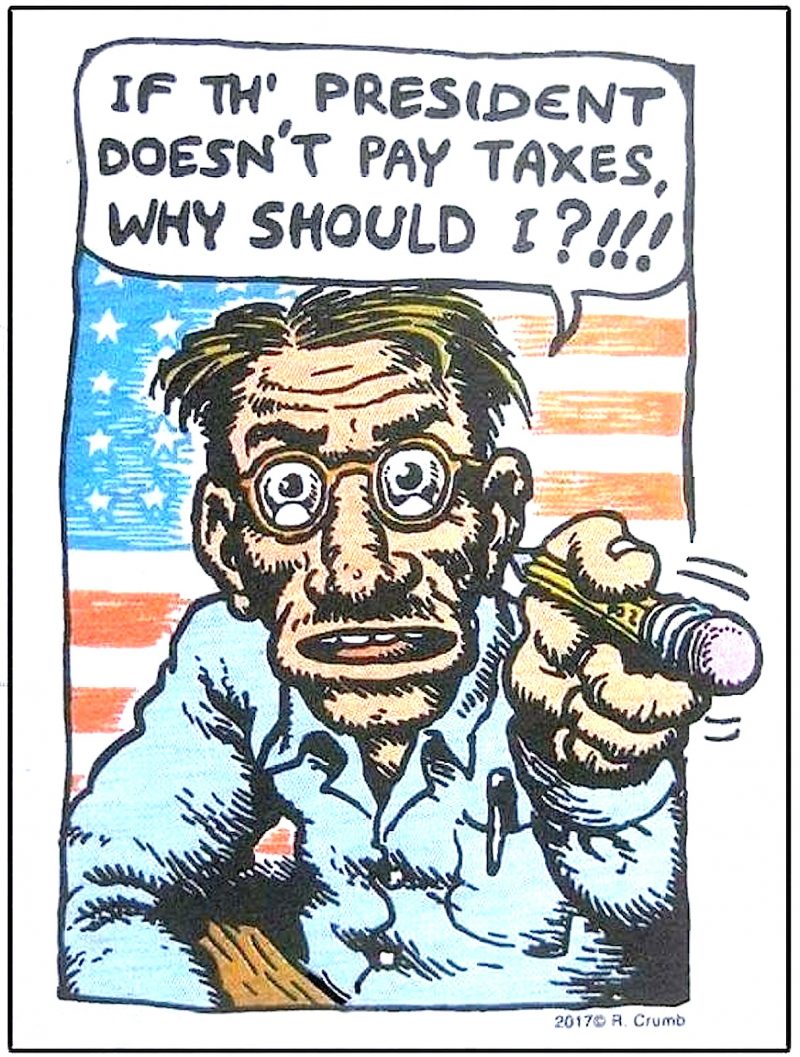

Robert Crumb, the American artist currently living in France, recently produced a simple self-portrait criticizing Trump’s tax dodge. Widely circulated on social media, Crumb’s drawing has been printed t-shirts and released to the public for sale ($20), “In protest to Trump’s refusal to release his tax returns and that he possibly didn’t play federal tax for many years.”

But, Paris-based art critic Violaine Boutet de Monvel doubts art in and of itself can be an effective means of fostering political change. “I believe we’re political in the street,” says Boutet de Monvel, who writes for London’s ArtReview. “That’s the most efficient way to voice our concerns and beliefs. I do not believe that art as such can be an efficient political tool. It’s not its role.”

Economically, art can absolutely be a powerful political tool, and recent anti-Trump charity shows of work to spread awareness and put money in the hands of those who need it, is effective, but not as an engine of change by itself. But, Boutet de Monvel re-affirms, “Resistance happens in the street, without detour!”

Screen grabs, hashtags, and memes

Trump World’s art world citizens’ discussions, and works about politics and social issues, have largely migrated from canvas to screen. Indeed, just type in your favorite word into this hashtag analyzer and you’ll see if “#impeach” or “#dumptrump” is gaining ground.

Surfing Instagram (on waves of hashtags), I found thousands of memes–political photographs adorned with clever, sometimes savage texts. In fishing for commentary on the efficacy of political messaging on social media I received this one from an artist who wanted to remain anonymous: “I have never been a fan of topical art in general; [it] doesn’t seem to have staying power. Political art is an expression of a particular social climate and as such will shift just as swiftly. I suppose, it depends on how you define art. If you allow it to include neatly packaged and consumable creative work (like memes), then it is effective. Natural selection determined by the mass’s lowest common denominator of intelligence and critical thinking.”

Thus far it’s hard to say exactly what these artists or institutions have accomplished. Occupy Wall Street (2011) did very little to change the behavior of banks and the 1 percent; Occupy Museums, an off-shoot of the OWS group, is virtually unknown outside of a number of bloggers and interested artists. Trump and Republicans on the Capitol Hill will most certainly cut funds to the arts, National Public Radio, PBS, and most anything cultural.

Noah Becker, the White Hot Magazine of Contemporary Art publisher (he’s also a painter), remains optimistic. “I would hope that the new administration invests in artists and invests in art, or at least values the importance of culture beyond blue-chip million-dollar art as a symbol of wealth.”

Our art world can and does mesh with our democracy in ways that are both obvious and hidden and the two are often in conflict with each other–and complacency. “Functioning democracies require the engagement and work of citizens,” says Johnson of Art F City. “It doesn’t require an excess of formalist abstract painting. I’m not interested in the work of right-leaning artists. We have Neo-Nazis shutting down anti-Trump statements at museums. This is not a curiosity. It is a battle and we need to be prepared for it because it’s not going to be pretty.”

Culture workers–artists, curators, museums, galleries, and even collectors–will need to choose their weapons well at this highly charged cultural crossroads. Will a paintbrush, pencil, theater, soup kitchen, computer, parade, YouTube, or even cash suffice to forge meaningful change? My guess is the means of engagement will inevitably evolve to match the challenge, but that won’t include simply “liking” a picture of a naked and pregnant Trump in the arms of Vladimir Putin.