Venice is a Byzantine labyrinth of water, stone, and brick and some 400 bridges criss-crossing a myriad of waterways. Getting lost is one of the special offerings of Venice. Wending your way through its intricate web of narrow, tapered streets, you are left with the sound of your own footsteps echoing through the centuries.

Venetian retreat

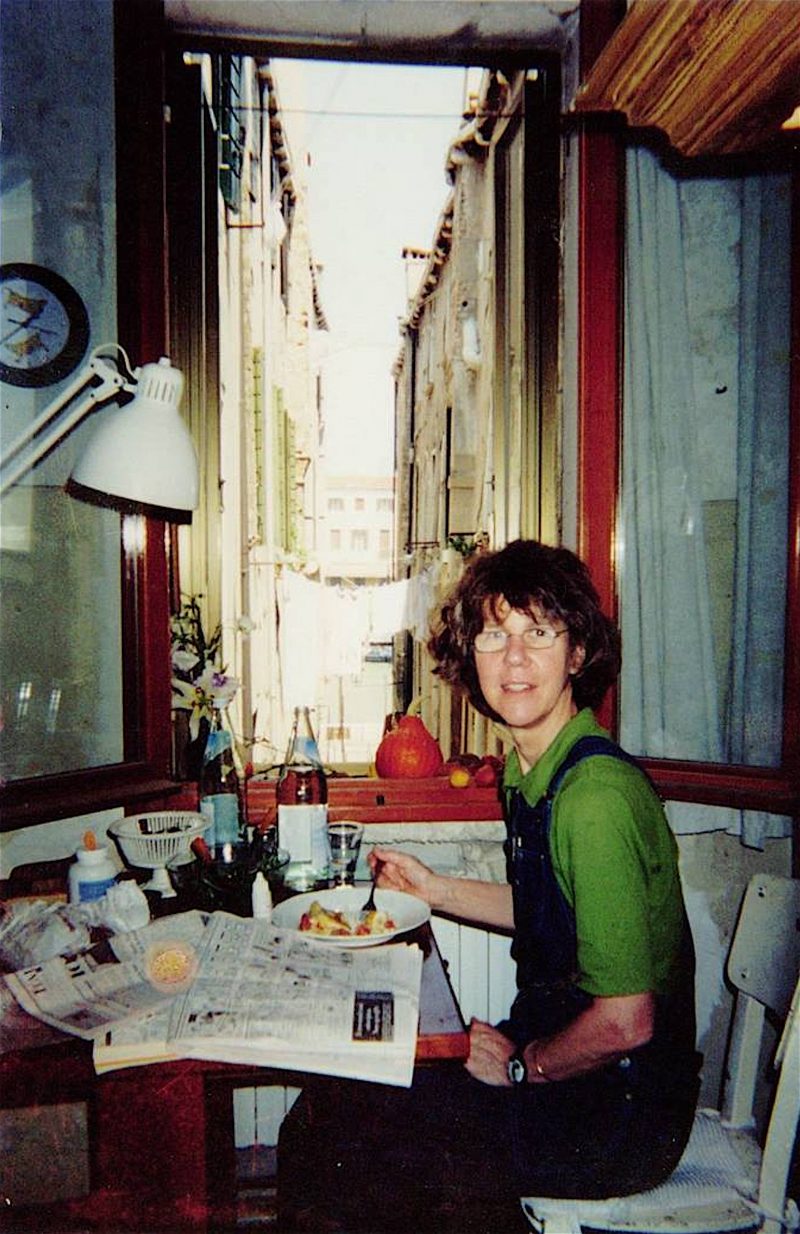

I returned to the “floating city” last week to visit artist John Himmelfarb who had received a month-long studio grant from the Emily Harvey Foundation. The Foundation operates on shoe-string budget (please feel free to donate), in supporting contemporary artists who come here year round to research, write, paint, draw, think, and walk.

While John had never met Emily Harvey, the Fluxus art dealer who passed away in 2004, Emily created a foundation that would speak to artists for decades to come. “The opportunity to come and work in Venice–a city that is empty of cars, trucks, and wheels in general a real gift,” said Himmelfarb.

“Much of my work had to do with urban materials–bridges, ironworks, construction cranes–a bird’s eye view of the city,” he explained. “When I applied to the EHF, I wrote that my work was architectonic with a nod to the idea of map making.”

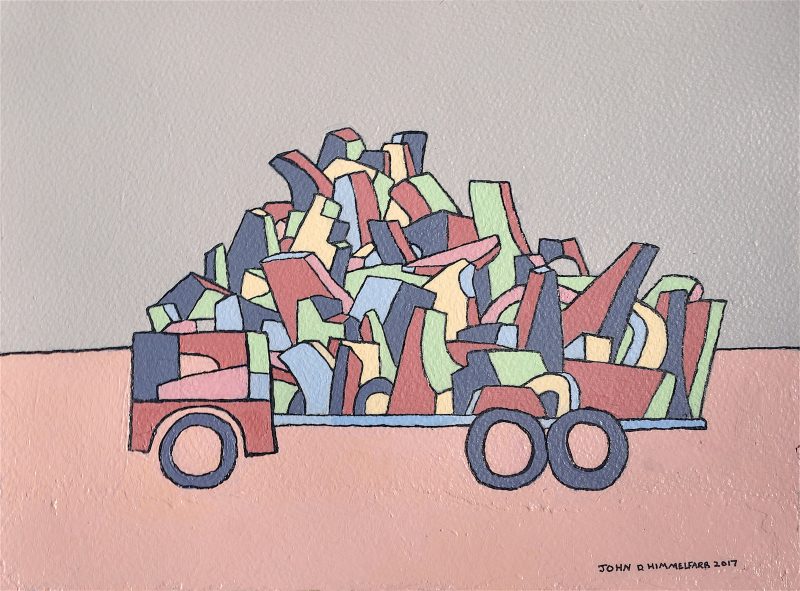

Chicago-based painter and sculptor Himmelfarb’s recent projects consist of drawing, painting and assembling trucks–both toy-sized sculptures and actual vintage pickups loaded with an assortment of rusted objects and found detritus. His works are a kind of history on wheels, sojourners in time. And Venice, with its pronounced absence of cars–and wheels in general–proved an interesting place to uncover the essence of our attachment to motion and John’s current interests.

In his studio near the Mercati di Rialto and the Pescheria (the fish market), Himmelfarb had produced a small truck painting that mimicked, in its patterning, the Venetian sestiere (districts) as they are sliced up by the network of canals that spiderweb through Venice. “Traghetto,” (2017) a 9” x 12” acrylic on paper, employs Himmelfarb’s signature line work and riffs off the pushcarts the city employs to ferry the garbage from the streets to waiting trash boats.

Peggy’s house

I asked Himmelfarb what he’d seen in his first few weeks. A tour of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection yielded, he said, a 20th-century view of Modernism and Conceptualism. Guggenheim was an American icon in Venice for decades. She famously launched the Art of the Century gallery in New York just as World War II cast its pall over Europe, and she created an aesthetic home for most if not all the Surrealists in New York. Her home in Venice features a world class art collection that attracts tens of thousands of visitors annually.

In one of the galleries, John said he was particularly drawn to Tony Cragg’s “Bottles on a Shelf” (1981). Known for his reclamation of objects washed by time and sometimes the oceans, Cragg placed five plastic bottles on a painted wooden shelf. It’s all quite simple and direct, and probably puzzling to the average viewer, but Cragg helped to rewrite the book on sculpture, oftentimes arranging bits of washed up plastic spilling off a wall to the floor. His innovations echoed movements in the 1950s and early 1960s that removed the pedestal from sculpture, embraced life in the use of ordinary objects and focused on immediacy.

“The Cragg reads very flat,” said Himmelfarb, almost like the Ellsworth Kellys in the next room. “The bottles were most certainly washed up along some shore; I’ve used things that have been cast away and moved through the cycle once. I see this piece not as just a concept about recycled work, but a stab at realism in primary and secondary colors.”

Miracles & Madonnas

I had to take John and his wife, Molly, who accompanied him on this trip, to one of my favorite churches in Venice the Chiesa di Santa Maria dei Miracoli (1481), the marble, box-like structure designed by Pietro Lombardo (c.1435-1515) to house and protect a single painting–an icon of the the Virgin Mary with Child. This prime example of Venetian Renaissance architecture is one of the more severe of Venice’s 139 churches. It is empty of much of the Christian objects one finds in other churches here, though the vaulted ceiling is decorated with portraits religious prophets. The “Church of Miracles” was the object of a 10 year “Save Venice” campaign to keep it from bursting apart from salt, a constant worry in a city that is regularly inundated by rising sea waters, a reality exacerbated by global warming.

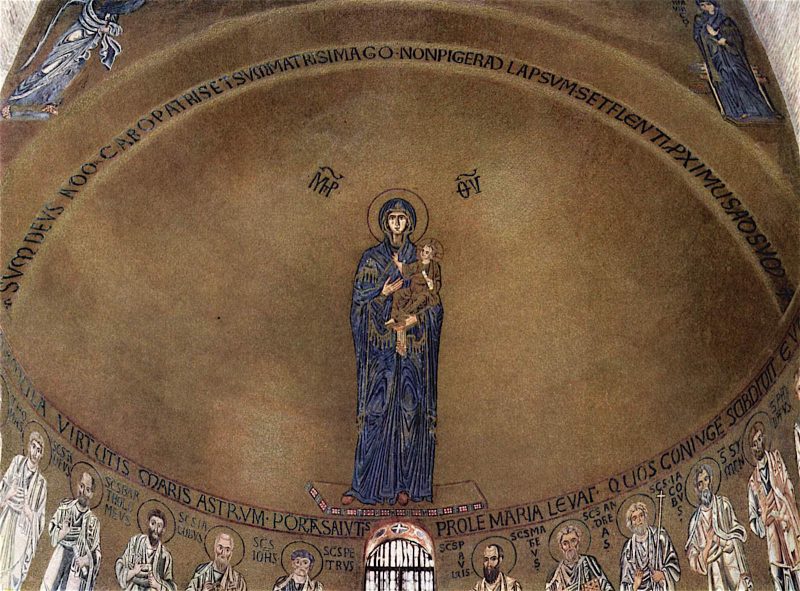

Sitting in a lagoon in the north Adriatic, Venice is a work of art in itself, but it is also surrounded by other islands that were once more important historically and commercially. Himmelfarb told me about a visit to Torcello, an island some 40 minutes from Venice by vaporetto (boat) to see the ancient basilica there. First constructed in 639 and enlarged several times since, the church was once the capital of Christianity in Northern Italy before Venice’s San Marco drew both commerce and the faithful. Within the main apse of the medieval basilica, a standing 11th-century mosaic of the Virgin with child overlooks the congregation.

“The Madonna consists of thousands of mostly dark blue tiles,” said Himmelfarb. “And she is like a giant Giacometti surrounded by an enormous, minimalist field of tiny gold mosaic tiles. It’s hard not to be fascinated with the workmanship. Great works of art are always religious experiences.”

If not a religious experience, walking in Venice, though ordinary, provides a unique kind of awareness. The hundreds of foot bridges everywhere are each “a little sculpture,” Himmelfarb noted. “Venice forces you to really consider construction, movement and urbanism in its most basic manifestation; the bridges and their design and their site specificity–changing elevations, odd angles–gives breadth to notions of measurement, material, direction, and intimate and public spaces.”

“You can’t get around Venice very easily without looking at maps. And scale is different here, of course. But in Venice you’re on foot and walking here is like wandering around inside a sculpture–moving from open and closed spaces. Endlessly interesting–the pavement, the water, smooth and rough textures of the brick and stone–you feel as if you’re in a work of art.”