In Unwritten Wills, Nandini Chirimar uses still life drawings to explore the themes of memory and loss. The objects profiled in these works belong to Chirimar’s late father and her nanny, before they both passed away within a span of a year in 2015. Through these meticulous illustrations the artist has formed an intimate connection with her father and nanny’s life histories. The creative decision to present some of these personal items in their original form, like one of the metal trunks and its contents belonging to her nanny, alongside their two-dimensional renderings in pencil made me feel like I was sharing in a tangible and immediate experience with the departed. The artist transforms the solitary, contemplative act of drawing itself into an act of commemoration and remembrance of her departed loved ones.

Worldly goods

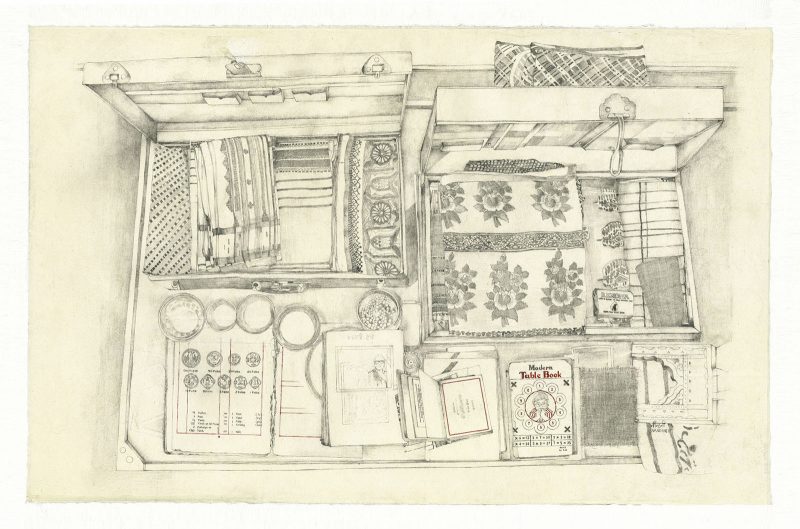

Peering inside this metal trunk, I saw an unopened bar of Rexona brand soap, some faux gold bangles, a large collection of colorful saris, steel bowls, and plastic mailing envelopes. Placed next to the trunk are various photographs of the artist’s and the nanny’s family, her nanny’s folded napkins as they were when she was alive, some of her notebooks including a textbook on basic mathematics, and several aerogrammes or postcards that bear the nanny’s handwritten correspondence in her and the artist’s native language of Hindi. As I examined the writing in the notebooks and aerogrammes it dawned on me that I was witnessing first hand the fervent attempt, by an uneducated woman, to read and write.

If you substitute the brand of items and cultural dress, this plethora of personal items could belong to anyone’s nanny. It further reinforces the brilliance of Chirimar’s drawings that attempt to cross the boundaries of race and generations, and allow for a similar connection to material things accumulated in life, and discarded or left behind after death.

My focus shifted from the three dimensional experience to the two dimensional interpretation of these personal objects. The large black and white drawing on Japanese Kozo paper titled “Found in Her Trunk” is a delicate pencil rendition of the metal trunk and all its contents. The trunk is placed alongside a second open trunk and additional items like an identity card, steel cups filled with Indian spice seeds, paper napkins and an accounting ledger that depicts various denominations of Indian currency coins. We are shown a part of the nanny’s successful attempts at applying her learning of math like in the rudimentary calculations depicted in the ledger that she managed. The choice to draw on Kozo (mulberry) paper, made from a widely used fiber due to its unusual strength, adds to effect of transferring such a fragile experience and memory of Chirimar’s late nanny and father.

Across the divide

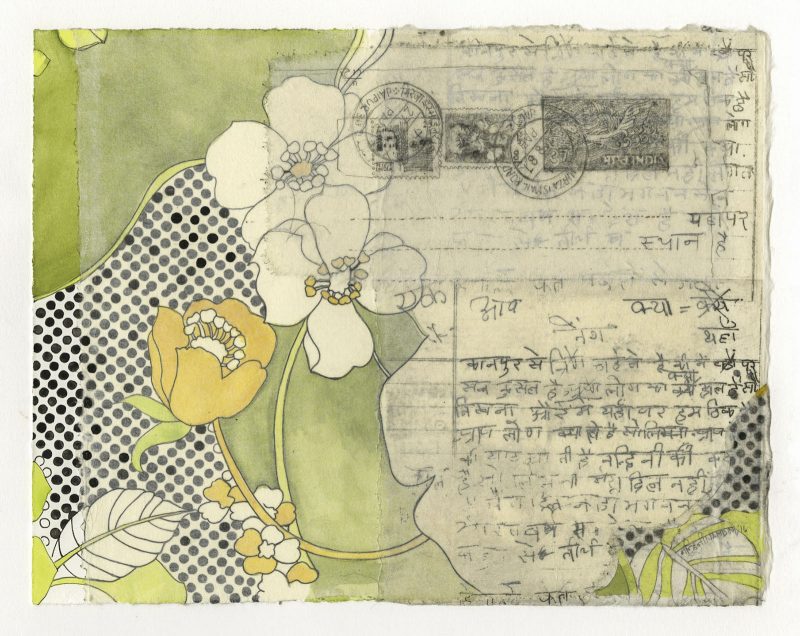

In the same exhibition Chirimar has elected to showcase a secondary group of mixed media drawings that give visitors a way to appreciate the diminishing skill and use of handwritten correspondence. In the piece titled Aerogramme, the artist incorporates her nanny’s handwritten postcards, sent from her native city of Kanpur located in the state of Uttar Pradesh, with objects like flowers and leaf motifs referenced from her nanny’s favorite saris. These aerogrammes were written while Chirimar was attending university in the United States. The Hindi text, though faded and is missing words in some areas, allude to some of her nanny’s daily routines, her perspectives on living in Kanpur, and her longing to learn more about the artist’s life in America. Through her writing we sense an awareness, dedication and discipline that her nanny maintained to painstakingly pen words that she taught herself, and use this newly acquired skill to keep in touch with the artist and her family during the days when social media platforms or apps were nonexistent.

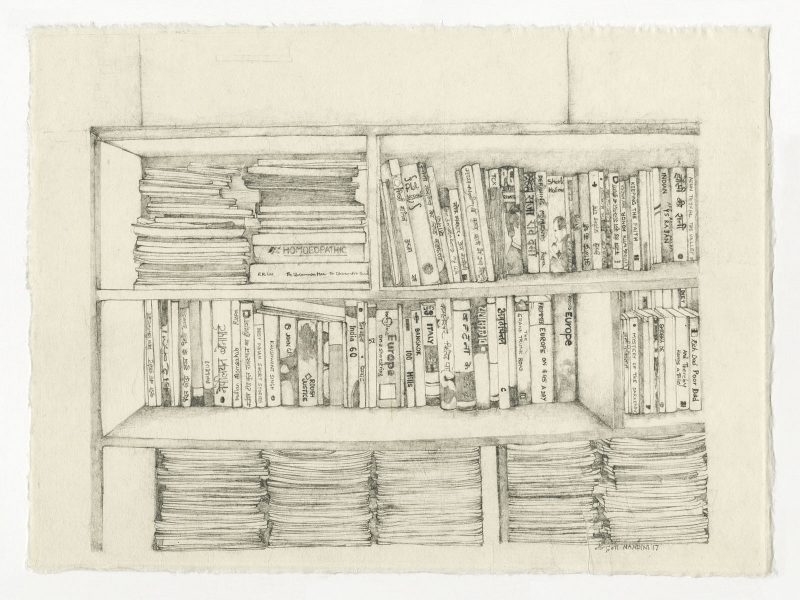

In the drawing also titled “Unwritten Wills,” Chirimar documents the voice and embodiment of her late father. In this drawing, the artist has illustrated the various books that represent the varied interests of her father. We see the spines of several books ranging from a biography of Napoleon Bonaparte (titled in Hindi), travel books like the Let’s Go series on Italy, books on financial self-improvement like Rich Dad Poor Dad, to books on faith and so on. Reflecting in her artist’s statement on what she learned from this exploration of her father’s bookshelves, Chirimar says, “I thought about how he must have felt when he read each book, how it might have changed him a bit, and how that change might have seeped through to my own life.”

As I continued to observe the drawings depicting the personal effects left behind by Chirimar’s late father, I couldn’t help but reflect on my late father and some of the most treasured things he left behind. I wondered how much of that shaped my thoughts and perspective on the world when he was alive, and how much of it continues to do so today.

Chirimar’s imagery of possessions that have lived on beyond their owners underscores the reality of her loss. Her works suggest an alternate view of a still life, one that has replaced the joy of life with the joy of art.

Unwritten Wills by Nandini Chirimar will be on view until March 25, 2017 at the 12 Gates Arts, 106 N. 2nd St..