Twenty years ago I attended an international symposium in Amsterdam on the conservation of modern and contemporary art–the first of its kind. The organizers presented ten case studies of late 20th-century artworks that were not in a condition to be exhibited and challenged traditional approaches to conservation, including a Jean Tinguely kinetic sculpture whose motor no longer functioned, a commercially fabricated plastic plaque by Marcel Broodthaers which was cracked, and a wall hanging by Mario Merz made of neon lettering fastened to a frame covered with wax-coated gauze.

From art to artifact

The Dutch organizers had assembled teams of conservators, curators, art historians, conservation scientists, and philosophers to develop suggested approaches for each work, and the symposium was intended to prompt further discussion among colleagues. The Americans in attendance were all conservators, except for me. In 1997 the subject did not seem to interest American curators or academic art historians.

The only example presented at the symposium which provoked a unanimous response was the Tinguely. Art conservation standards prohibit replacing the motor–as they would also prohibit reconstructing the neon used by Merz–and the artist intentionally used second-hand motors that did not function smoothly, but had idiosyncratic motions. Everyone agreed that a kinetic Tinguely that could no longer move should not be presented as his art. It was now an artifact, suitable to be seen only within a study collection.

Museums owning Tinguelys have not agreed, and I have seen lifeless examples on view in numerous museums in Europe and the U.S.. The National Gallery of Art recently showed one from the Virginia Dwan collection along with a video of the piece in motion. The only functioning pieces I have seen were at the Tinguely Museum in Basel, and I do not know how long they will be able to keep those functioning.

The medium is the message

Artworks with working parts–which include those involving light and/or sound, as well as motion–and media art of all forms are subject to similar challenges. By now we have all encountered 16mm film, Betamax video, glass slides and digital files that we can no longer access or view because of changing technology. And unlike literature, where the content can be migrated from one format to another with no loss of artistic value, in the visual arts, the format is the artwork.

Twenty years later the questions have only become more acute. Much art intended to be ephemeral or with a built-in lifespan because of poor or unstable materials, was once of no commercial or archival interest. But now it has entered museums and private collections, and the field of contemporary art has become a burgeoning subject within art history departments. I can only hope that people working in the field understand the complexity of questions such works present, and the three books under consideration provide some guidance.

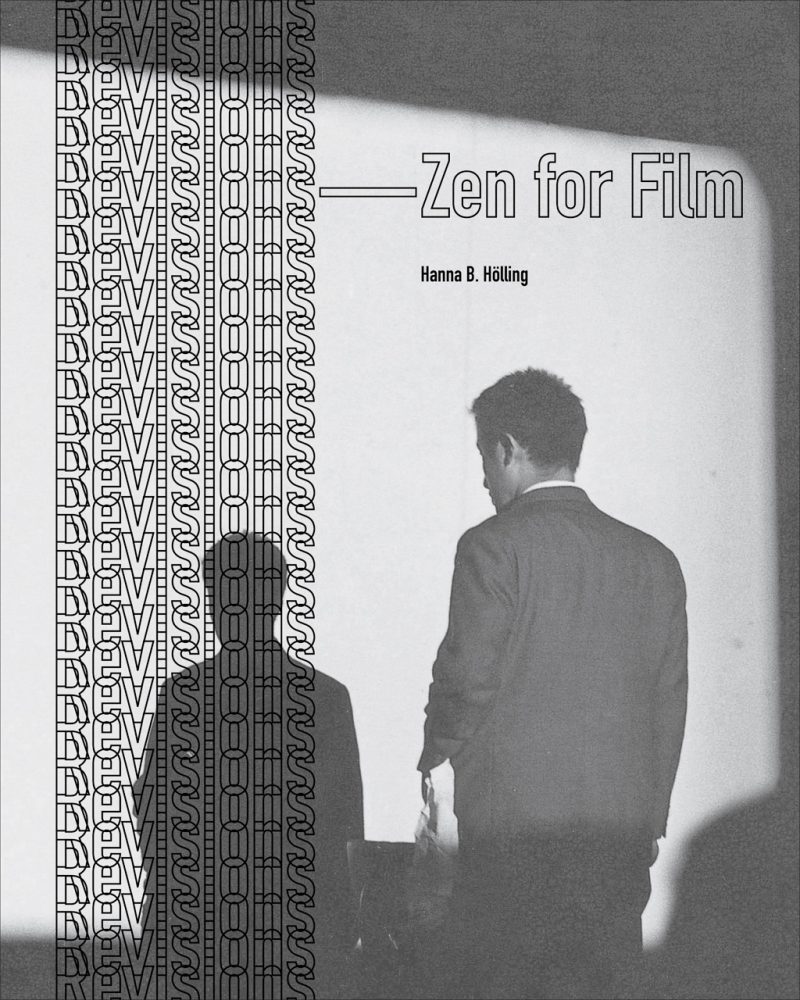

New monograph on Nam June Paik

Revisions – Zen for Film addresses Nam June Paik’s “Zen for Film” (1962-64), a work which raises the most profound questions of what, physically and conceptually, the artwork is, what there is to be conserved, and what can–or should–be exhibited. The questions are entirely art historical and philosophical, not technical, and the book should be required reading for all students of contemporary art. With “Zen for Film” Paik ran a length of clear leader through a projector–there is some question as to whether the film was looped or linear. As it played it acquired small artifacts of wear such as dust and scratches. The projected film might also interact with the audience, in the form of shadows cast in real time. The work bears an obvious relationship to John Cage’s 4’33” (1952), during which the performer sits for the specified time and the ambient sounds of the audience and hall provide the music.

Hanna B. Holling, a scholar and conservator, describes her multiple exposures to “Zen for Film”: as it is most generally known, captured in a photograph by Peter Moore in 1965 which shows the artist from behind, standing in front of a lighted screen on which he casts a shadow; in a museum exhibition, using a projector with blank film–film neither used nor authorized by the artist; in another exhibition where it was presented in digitized form–a technical inevitability for most works of film and common to current museum practice, despite the usual museum insistence upon originality; and in yet another museum which displayed it in the form of film in a canister, as part of a Flux Film Anthology, which itself has a contested history.

“Zen for Film” as distributed by Flux Films

After fifty years is “Zen for Film” an experience, an object, a projection, or a relic? Holling examines the early history of the work, contemporaneous artworks that raised similar questions, and protocols for institutions that would borrow and exhibit examples from various public collections. Some of Holling’s questions are now being answered by the artist’s estate, museums, and film archives–and they offer inconsistent answers. “Zen for Film,” whose subject is entirely bound with its materiality, raises particularly complex questions, and Holling is thoughtful, dogged, and modest in searching for answers. Her examination raises points common to enough 20th- and 21st-century works that art historians concerned with the record as well as curators and conservators tasked with exhibiting and caring for them will have to acknowledge them.