George Nakashima, the Japanese-American architect, woodworker and furniture designer, is mostly known for his unique furniture design and woodworking technique depicting the natural forms and patterns in wood grain of the tree, but the artist also designed a number of significant architectural structures during his distinguished career. Upon learning about Nakashima’s past influences through the enlightening documentary exhibition, A Woodworker’s Retreat: George Nakashima’s Arts Building and Cloister at the Harvey and Irwin Kroiz Gallery, I was drawn particularly to the time he spent living and working in Southern India.

Combining natural and modern material

Nakashima (1905-1990) began his professional career as an architect, not as a woodworker. Born in Spokane, WA, he received a bachelor’s degree in Architecture from the University of Washington in 1929, and a master’s degree in Architecture from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Boston in 1930. Nakashima moved to Japan where he joined the architectural firm of the Czech-American Modernist architect, Antonin Raymond, who had been working on notable projects including Frank Lloyd Wright’s Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. Raymond’s interest in combining natural materials with modern materials like concrete to achieve the possibility of new texture and details eventually saw him and Nakashima move away from Wright, who had ignored these possibilities with simple materials. When Raymond’s firm received the commission for the “Golconde Dormitory” project, Nakashima was assigned as a project architect to oversee the execution of the construction and interior furnishings. It was to become an endeavor that would inspire Nakashima’s design process and move him closer towards a career as a spiritual woodworker.

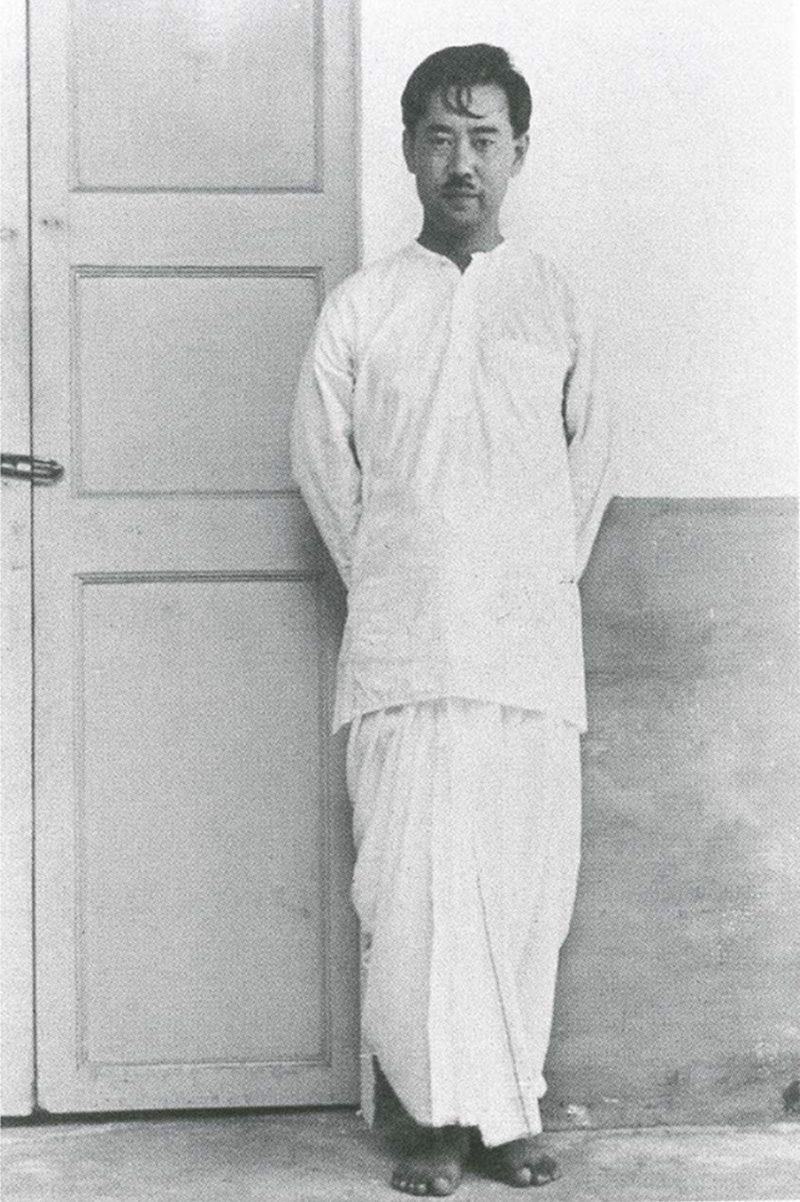

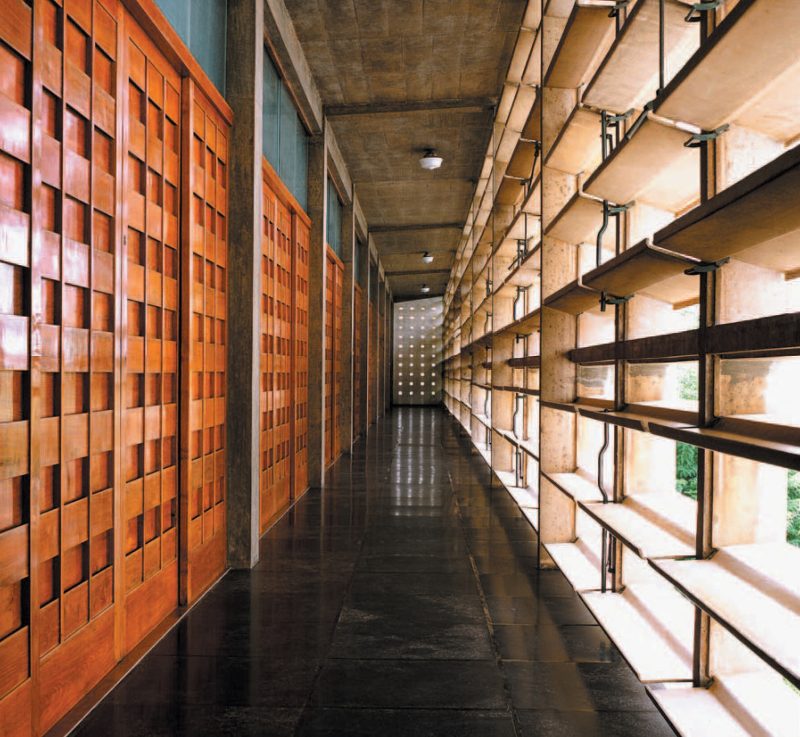

Located in Puducherry, formerly known as Pondicherry, the Golconde Dormitory (1935-1942) was one of the first Modernist buildings ever designed and built in India. This unique structure combines the tenets of modernist architecture, such as simplicity, lack of ornament and clean lines, with the practical impositions of the surrounding landscape. Factors such as the hot, humid and tropical climate, and the political unrest in Asia and Europe, meant that there were limitations in the types of construction materials that could be used. Having to adopt an inflexible economy, uncompromising construction standards and environmental sensitivity into his design process, Nakashima wrote in his diary, “since the design was to be completely open, the task was to build a straightforward structure that would solve the problems peculiar to this type of architecture in a tropical country.”

Nakashima explored the available building materials and refined their details through the construction of scaled models. This approach, which he would continue to use for later projects, resulted in the selection of reinforced concrete that would be cast-in-place for the Golconde Dormitory project.

While working on the project for six months he also became a disciple at the ashram and was re-christened “Sundarananda”, which translates from Sanskrit to “the one who delights in beauty”. This pivotal step in his career allowed Nakashima to gain insight into the practice of Integral Yoga and the transcendent sense that inspired him to develop his own philosophy of creating utilitarian objects of beauty through spiritual woodworking.

Finding freedom

Upon returning from India in 1939, Nakashima got married and soon began working as an architect for Ray Morin in Seattle, Washington. He also set up his own furniture shop and taught furniture making part-time. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Nakashima along with his family was interned at camp Minidoka, in Hunt, Idaho. There he met Gentaro Hikogawa, a skilled carpenter by trade who taught Nakashima about traditional Japanese carpentry, before Nakashima’s release in 1943 through the advocacy of Antonin Raymond.

Following his release from the camp, Raymond invited Nakashima to join him at his farm in New Hope, Pennsylvania, where Nakashima settled with his wife and two children, focusing his time on furniture making and farming.

As Nakashima’s furniture making gained prominence in the American craft movement, he once again turned to architecture to conceive and build a complex that would include the Arts Building and Cloister in New Hope as a private sanctuary for artistic exchange and his spiritual practice. Using the International Style infused with elements of traditional Japanese architecture, Nakashima combined natural materials including local stone, white stucco walls, and simple wood trim, and created asymmetrical designs that feature exposed framing, ribbon windows, glass walls, and an open floor plan, thus allowing for a juxtaposition of architecture, furniture and landscape all contained within a natural environment.

Although today the structures within the New Hope complex have entered into a state of deterioration due to natural aging, Nakashima’s quest for integration of humanity and nature endures in his construction drawings, architects’ letters, and journals and in the extensive documentary photographs of the artist’s works in furniture and architecture, on view in this delightful exhibition. Catch it before it ends on June 30.

A Woodworker’s Retreat: George Nakashima’s Arts Building and Cloister, to Friday, June 30, 2017, Harvey & Irwin Kroiz Gallery, Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania, Fisher Fine Arts Library, lower level, 220 South 34th Street, Philadelphia 19104.