Works from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s modernist collection currently fills the museum’s entire rotunda – through Sept. 6, 2017 – and anyone interested in modernist painting and sculpture should run to see it, and will probably want to return multiple times. The Guggenheim functions largely as a kunsthalle, presenting one temporary exhibition after another, with only the Thannhauser Collection on permanent view. What most visitors know of its collection comes from seeing it included in temporary exhibitions, either at the Guggenheim or elsewhere. And it is an extraordinary collection. But more than that, the reason to put it on the “must do” list is that the paintings are astonishingly glowing and clean – you will never see a group of works this vintage that look like these. This is partly due to recent conservation treatment, but for many of the paintings it is a result of their spending most of their time in storage, away from movement, light and dust. It is the one consolation of keeping such an important collection away from public view.

Meet the Collectors Who Shaped the Guggenheim

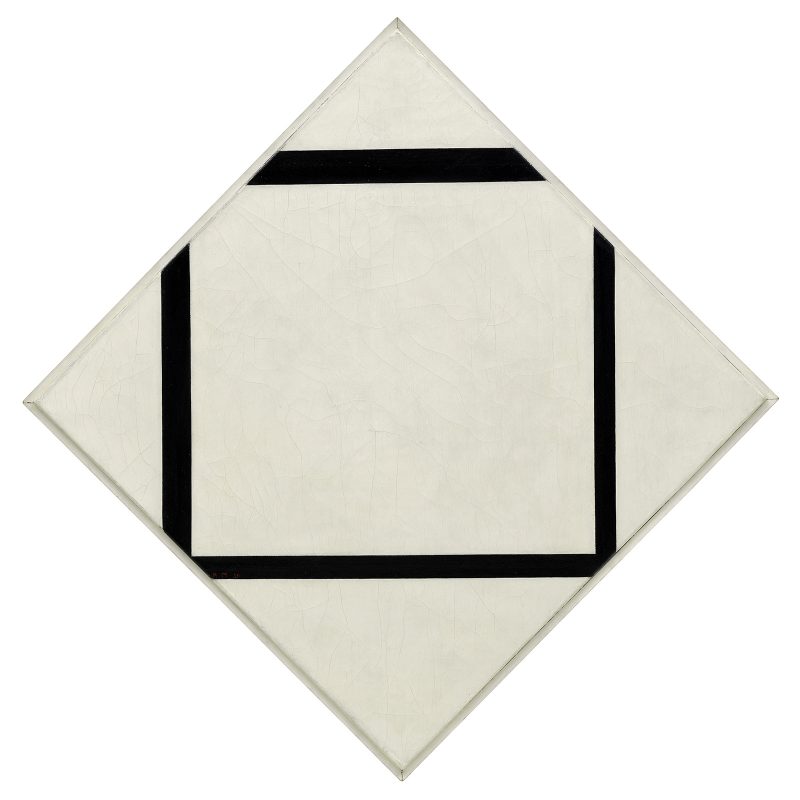

Titled “Visionaries; Creating a Modern Guggenheim,” the exhibition has been has been organized by curator Megan Fontanella around the collection assembled by Solomon R. Guggenheim and works acquired by five other early supporters of modern art. They were all artists or dealers, hence professionally involved with art, and championed European modernism to unaware and/or unconvinced audiences in the United States. The inventory and personal collection of the émigré, German art dealer, Karl Nierendorf, largely Expressionist work, was purchased by the museum. Justin Thannhauser, another German dealer who moved to New York, donated work from his collection by Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, and School of Paris artists in the 1960s. The museum acquired a range of work from the estate of Hilla Rebay, a German painter who advised Guggenheim on his collection and was the museum’s first director, and from Katherine Sophie Dreier, painter and collector best known for founding and overseeing the collection of the Société Anonyme, a group she founded along with Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray.

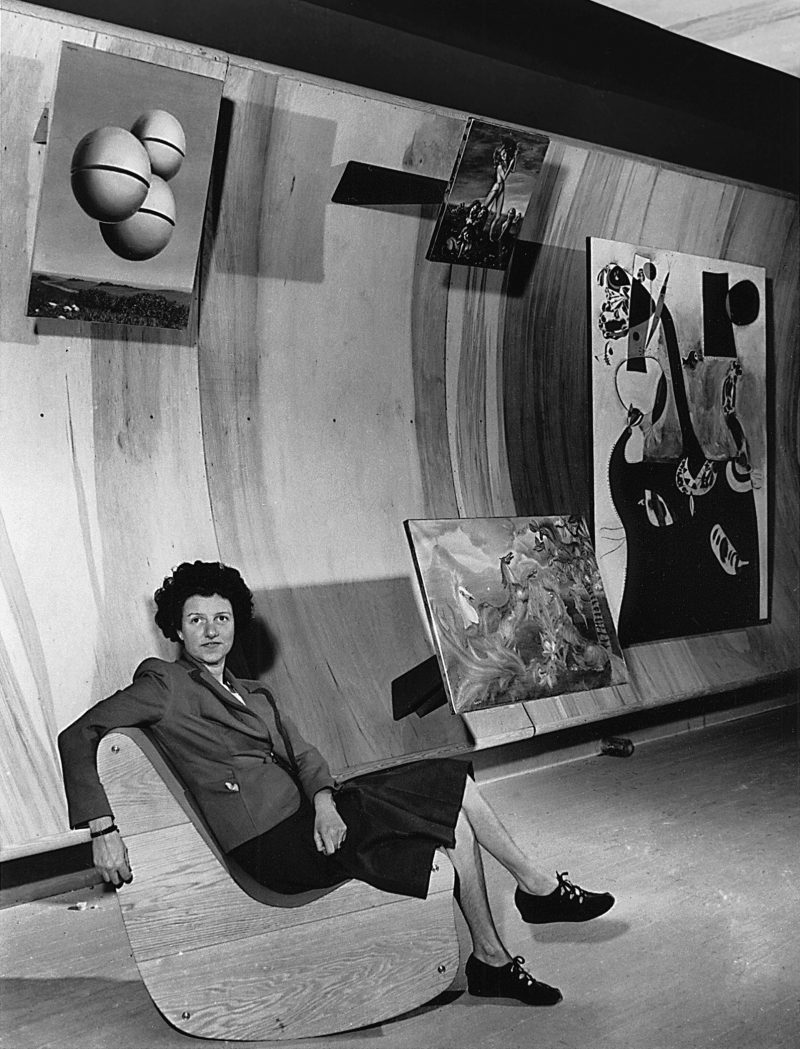

Solomon’s niece, Peggy Guggenheim, was an influential collector and dealer who made major contributions to the New York art scene during the 1940s. She commissioned the Austrian architect, Frederick Kiesler, to design the most inventive interior ever for her gallery, Art of This Century (1942-47), and commissioned Jackson Pollock to do his first wall-sized painting for her apartment. She left her collection to be exhibited to the public within her Venetian palazzo, under the auspices of her uncle Solomon’s New York foundation.

Abstract Expressionism Revisited

The day I visited began with Douglas Wheeler’s installation, “PSAD Synthetic Desert III,” on view through August 2, which I discussed previously. On exiting the Wheeler I found myself at the end of the exhibition, with work assembled by Peggy Guggenheim. I was in a bay exhibiting Jackson Pollock’s “Melody” (1947), a complex, non-objective painting with skeins of color that included a surprisingly-rectilinear, screen of fine, white lines across the entire field. A man was photographing his companion in front of it, as if the site had been marked “scenic overlook.” It made a better background for a portrait than Picasso’s “Demoiselles,” at MoMA, I thought, which is almost always obstructed by visitors who want a memento. Perhaps the museums could provide full-scale reproductions of favored paintings, explicitly to be used for photographs – so the rest of us could look at the artworks.

The preceding bay held Pollock’s “Circumcision” of 1946, and what a difference a year made! It is embedded with figures, some of which were easier to read than others. I made out a standing person at right, someone on a motor-scooter in the foreground, and at least two owls. Pollock often gave paintings of this period titles from mythology, but if he had a story in mind here, the title gave no hint of it.

Neither of these paintings was included in MoMA’s 1998-99 retrospective of Pollock, so will probably be unfamiliar to many visitors. Note: the catalog doesn’t include individual entries of the works, which would include provenance and exhibition history. That information is available in exemplary catalogs of both collections by Angelica Zander Rudenstein.

I had time to look seriously at less than a third of the work on view during a single visit, but one enjoyable aspect of the exhibition – Megan Fontanella is to be thanked – is work by several artists that I’d never heard of: Penrod Centurion, Georges Valmier, and Perle Fine, whose name rang a bell but whose paintings I’d never seen. And her painting here is a stunner. Fontanella obviously thought so, as it is hung to be seen across the spiral as viewers exit the elevator.

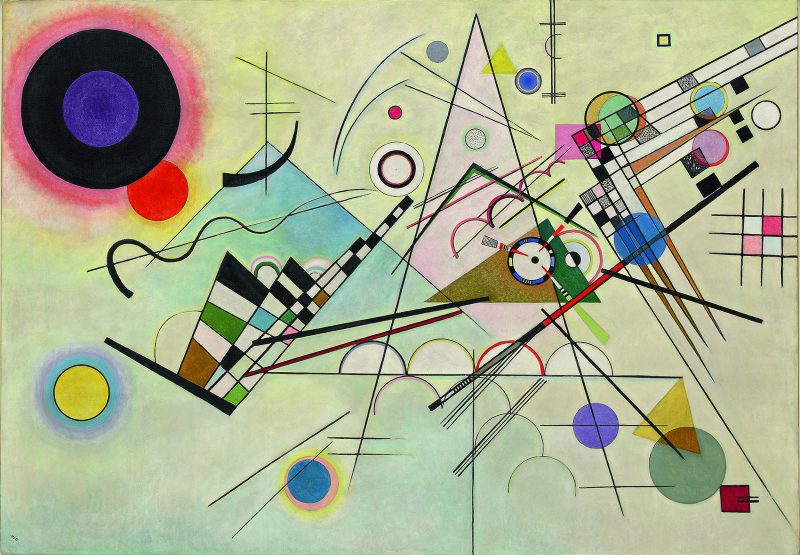

Highlighting Wassily Kandinsky

The Guggenheim is particularly rich in work by Kandinsky, and those on view are every bit as impressive as the paintings I saw on a recent trip to Munich and Vienna. The artist is the touchstone of Solomon Guggenheim’s collection and the story of non-objective art he set out to champion. I wish the museum would devote at least one floor of its tower galleries to work from its permanent collection, so the public could acquaint itself with the works over time – a long and happy romance, as opposed to the one-night stands that temporary exhibitions offer. But until then, this splendid exhibition will have to make due.

Visionaries: Creating a Modern Guggenheim is on view at the Guggenheim Museum, New York, until Sept. 6, 2017. More about the exhibition at the museum’s website.