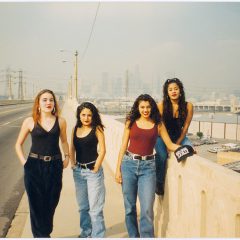

One Thanksgiving, while we sat around on the pillow-strewn floor after dinner, my now dearly-departed Great Aunt Eloise turned to me and said: “You couldn’t pay me to be anything other than black.” For me, a black woman who spends much of her time in environments designed for and by white people, the holidays have always been a source of such wisdom as I return to the faces and places who lovingly raised me. That’s probably why the family snapshots that artist Sadie Barnette mounts on holographic glitter paper continue to haunt me. They are so familiar that I can almost smell the corderoy, feel the pleated curtains, hear the music humming in the background. They offer momentary glimpses of cherished black life that persists, in the face of everything, and even in private.

Imani: When your family petitioned for your father’s FBI file through the Freedom of Information Act, were you surprised by what you received?

Sadie: We were surprised, mostly by the scale and the number of cities that were involved. He was a leader, but he wasn’t the most well-known person. He wasn’t Huey Newton or Bobby Seale, so the fact that this much information was kept on him means that everybody who was working against the war, or who was working for black liberation was under an incredible level of scrutiny. I was reading a book by Betty Medsger about the Citizens Commission to Investigate the FBI, activists who broke into the Media Pennsylvania FBI offices back in 1971, and one of the things that they found was that, at the time, every black student at Swarthmore was under surveillance — not just people in the BSU or leadership positions. So that’s the level of criminalization you face, just by being in your body.

I: How did you condense all of that information into such a cohesive show?

Sadie: The first time that I showed this work was at the Oakland Museum for the exhibition All Power to the People: Black Panthers at 50. It was really important to me that I show there first because it felt really contextualized. For that show, I created a wallpaper out of over 100 pages of the FBI files; I wanted to give the viewer the imposing feeling of just how massive the surveillance was. I was surprised, though, to find that viewers were actually attempting to read through all of the text. I think people have been really curious and hungry to see what these classified documents contain — to know what level of surveillance is possible.

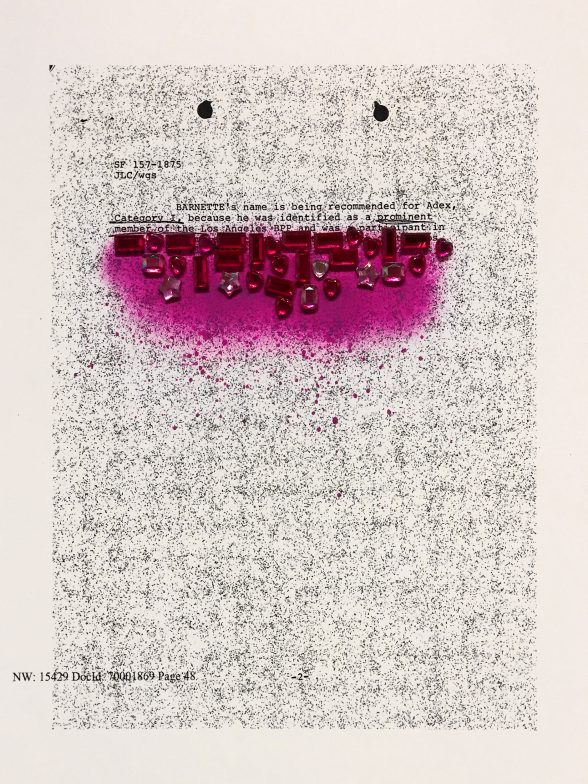

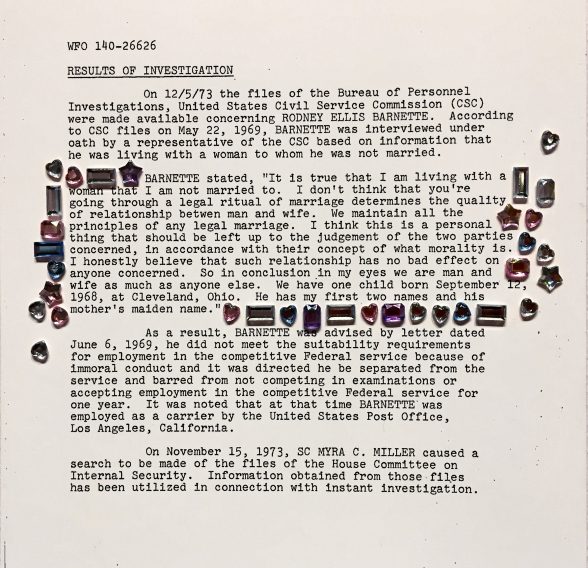

For this iteration I wanted to use a more linear presentation of the files, so that you can almost read them like a book. Also, I tried to highlight certain things. There are three pages that have to do with his military service and him receiving a purple heart (obviously that wasn’t enough to consider him patriotic). The experience of my dad getting fired from the post office, is another example. There is a page in which an informant reports that my dad was wearing a post office uniform at a Black Panthers meeting — that’s how they knew that he worked there. He was actually fired for cohabitating with a woman he wasn’t married to, and they have my dad’s statement about that too. One thing I wanted to pull out for people was the vastness of this web.

I: You’ve taken these files, which were already partially redacted by the FBI, and further obscured them using embellishments like glitter, rhinestones and pink spray-paint. Why?

Sadie: So there are two layers of competing redactions. After filing the request, it took about four years to get all of the files. It was a lot of back and forth, with them hoping that we would give up. It was a long process, and we didn’t use a lawyer — my family just literally googled “how to find a Freedom of Information Act request,” and wrote a lot of letters back and forth whenever things would be held up.

Of course the file comes with all these redactions, and I was really interested to see that they weren’t blacked out redactions, but rather these white squares, which I found graphically very interesting because of how I often approach negative or blank space as a charged space. So in working with those redactions, I wanted to put my own mark, and say that there are things that you can never know or understand about these black lives that you are trying to surveille. There’s this imagined unsurveillable glitter space.

I: How do you think about putting black lives on display in an art world and a larger society that are so rampantly anti-black? How legible should we make ourselves?

Sadie: I always hold this tension of how much to show and how much to hold back — how much to give or welcome people into something. How do you expose a part of something but acknowledge that it’s not everything? How do you invite the viewer into the living room but they know they aren’t going into the bedroom or the kitchen?

I: You’ve also made these painstaking graphite drawings that, from afar, just look like photocopied enlargements. Why invest that labor?

Sadie: Someone who was writing about my work actually called the drawing based on J Edgar Hoover’s signature a forgery — which I thought was interesting since it is technically a copy in my hand of his signature. But I labored over a moment that was so quick for him in order to really slow down that gesture. In the case of my reproduction of my father’s mugshot, it’s about turning that mugshot into a portrait. Drawing it by hand is an act of love — a daughter recreating her father’s image as a hero or freedom fighter.

A mugshot is intended to dehumanize someone. I was thinking about that little image sitting on hundreds of FBI desks and them thinking of this person as a dangerous 6’2” black male. It’s a life that could be so easily taken. So the opposite of that is a really labored-over, hand-made piece. At the same time, it’s so perfect that it conceals itself, which again is that play of letting people in but not all the way in. It’s not as expressive as a painting, where there is more evidence of the artist’s hand, but it’s there for you — if you know to look for it and take the time to question.

I: What is the significance of the show’s title?

Sadie: Dear 1968, Love 1984 is my overarching thesis, in a way. It’s an intergenerational conversation, a father-daughter conversation. 1968 was such an important year, both in the United States and internationally — in reality as well as in the popular imagination. 1984 was also a very important year, both because it was the year I was born, and because, even before it arrives, it’s a year that’s being thought about as the future because of George Orwell’s book. Now that we are past it, it becomes a kind of retro future.

I don’t really know what to say at this point looking back, so the piece is just an intro and a conclusion, the opening and the close of a letter. What goes in-between is where the things that are still beyond my language exist. It is an homage, a love letter, an apology, a thank you, but on its own, none of those quite sums it up, so I’ve left it blank.