“Lumia; Thomas Wilfred and the Art of Light” deserves the description “spectacular”- literally – even if most of its spectacle was on a domestic scale. Wilfred, a Danish-born and European-educated American, was an early twentieth-century pioneer of abstraction; among the small group of artists who aspired to create abstraction in movement, he was the only one working in the U.S.. This exhibition should have attracted lines around the block and if it didn’t, that’s the public’s loss. Wilfred’s work should be known to fans of early, abstract film by artists such as Viking Eggeling, Oskar Fischinger, Hans Richter, and Walter Ruttmann, to those interested in Rudolf Steiner, Mme. Blavatsky, Hilma af Klint and the relationship of spiritualism to abstract art, and for anyone interested in a fuller picture of the development of modernism as a prelude to the art of the 1960s. The exhibition (closed Jan. 7, 2018) was splendidly organized by Keely Orgeman for the Yale University Art Gallery and many of the works were conserved and brought back to working condition for the occasion.

The exhibition, which I saw at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, situated Wilfred in relation to developments in science, the broad public interest in Einstein’s concepts of special and general relativity and the relationship among space, time, and the movement of light. But the artist was self-trained as an engineer, despite his impressively-systematic studies – some included in the exhibition – of the workings of light and movement for his mechanical instrument, which termed the Clavilux; he later coined the term Lumia for his art form. A more likely stimulus was Wilfred’s interest in Spiritualism – Rudolf Steiner’s anthroposophy and Mme. Blavatsky’s theosophy – as well as his art studies in England, France and Germany in the period just following the publication of Wassily Kandinsky’s influential text, ”Concerning the Spiritual in Art.”

Wilfred’s art of slowly-moving patterns of multicolored light falls within a trajectory that began with the performances of the American dancer, Loie Fuller, who took Paris by storm in the 1890s with spectacles of moving light projected onto swirling draperies – which were of notable interest to artists from Lautrec to Rodin – to the 1960s psychedelic light performances of the Joshua Light Show and later installations such as Nam June Paik’s walls of video monitors, immersive cinema and video animation. Wilfred initially gave performances with his moving light equipment which he manipulated from a keyboard, much like an organ; its inner workings consisted of rotating platforms, mirrors and colored gels. Beginning in the late 1920s he made versions suitable for home display which required no more than the flip of a switch or turn of a knob; he presented them in cabinets that anticipate television cabinets in form, although a number of them are handsome enough to pass as proper furniture.

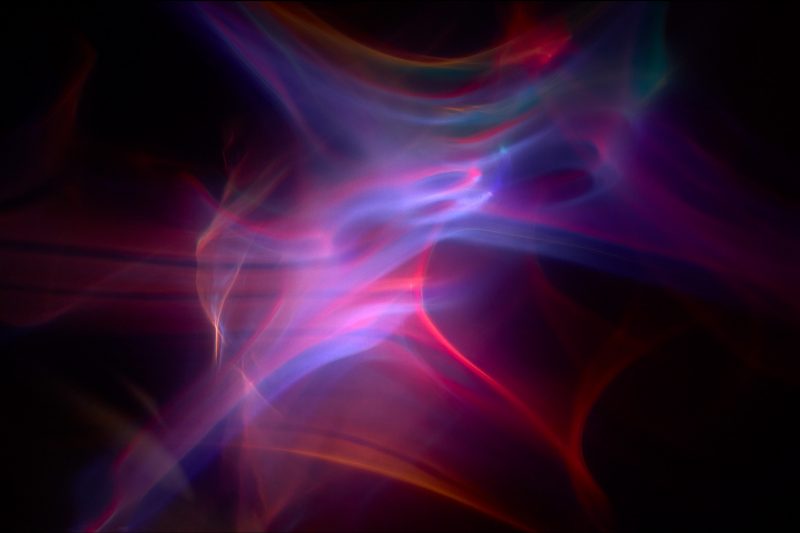

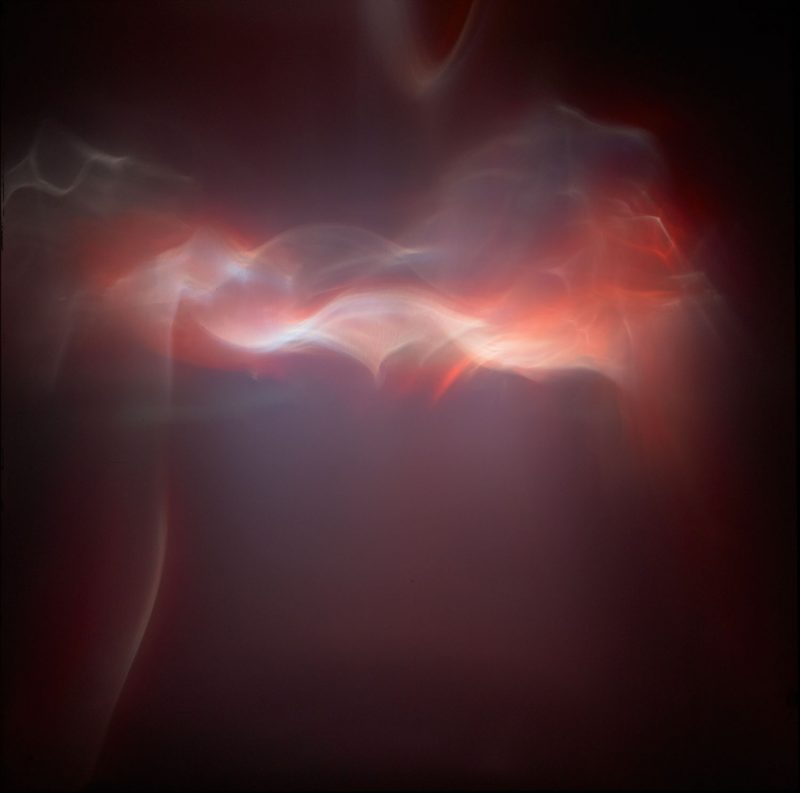

The Lumia create ghostly forms in slow motion (barring a single, still piece) that appear to be floating in space and morph over time; he produced a variety of effects from one work to another. They run through cycles that vary from several minutes to many years and it is easy to be seduced into a timeless state by their growth-like patterns. The most spectacular of the domestic Lumia has an unwieldy title: “Unit #50, Elliptical Prelude and Chalice,” from the first Table Model Clavilux (Luminar) series (1928). In contrast to all the others, which project light onto screens mounted in cabinets or on the wall, this projects light onto the ceiling above a table which contains the lighting, reflectors and moving parts.

Wilfred found an important patron in the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) which purchased a work in 1942 and included him in its third Americans exhibition in 1952 along with Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Clifford Still. The museum also commissioned his most impressive piece, “Lumia Suite, Op. 158,” which projected its patterns onto a 6 x 8-foot screen. Anyone who visited MoMA between 1964 and 1971, or 1973 to 1980 would likely know the piece because it was on continuous view, sited in a specially-constructed room just outside the entrance to the film auditorium. The work influenced an entire generation of artists interested in light as a medium and one of them, James Turrell, wrote a foreword to this exhibition’s catalog.

Since 1980 Wilfred’s reputation has disappeared from art history, to the point where he was not even cited in the catalog to MoMA’s 2012 exhibition, “Inventing Abstraction 1910-1925.” To a large extent his work has suffered from the problem museums have with all time-based art, whether mechanical, electrical or digital; anything that works eventually breaks down, and museums are even more committed to preservation than to display. This has already become a quandary for recent digital art. I suspect that the lack of Wilfred’s work on the market has also contributed to his neglect.

The exhibition was accompanied by an excellent catalog with essays on Wilfred’s history and legacy as well as a very interesting discussion of the mechanical operation of the Lumia and their particularly demanding conservation, with many of the internal, working parts illustrated. The Yale University Art Gallery has placed video documentation of fifteen works on line, which give a good indication of the range of Wilfred’s work, if not the compelling presence of the real thing. I can only hope that MoMA will reinstall “Lumia Suite, Op. 158” so that it can continue to work its magic on artists and viewers of the present and future.

“Lumia; Thomas Wilfred and the Art of Light” closed Jan. 7, 2018, at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.