“Outliers and American Vanguard Art,” organized by Lynne Cooke at the National Gallery of Art through May 13 is an extravaganza of paintings, drawings, sculpture, photographs and various hybrid art forms produced in the U.S. – for the most part – over the past century. For visitors who do not know the work of Judith Scott, John Kane, Bill Traylor or Gertrude Morgan it is likely to be a revelation. That said, the exhibition is too damn big by any standards; the catalog illustrates 277 works and acknowledges that it doesn’t include everything on view.

Artists outside the mainstream influence those in the mainstream

The exhibition explores the influence of art produced by artists without formal art education and working beyond the confines of the self-consciously avant garde art world – Cooke calls them “Outliers” – on artists who are part of that mainstream art world. The exhibition’s labels do not at all make clear which artists are which, nor does the exhibition meaningfully reveal what it is that the mainstream artists took from their untrained colleagues. Because of this it is curious but unknowable why Yasuo Kuniyoshi and Mary Heilman are shown rather than Alexander Calder and Jim Shaw, for example.

Outsiders or Outliers are not new subjects to the art world, and this exhibit shows the influence of market and money on what appears in museums

The subject is hardly new. Artwork by Cooke’s Outliers – the more usual term has been “Outsiders,” but terminology, and indeed criteria for the category have always been open to question — has been subject to a large amount of exhibition and academic study over several decades and across several disciplines, and is fraught with political and ethical challenges. What the exhibition does reveal is changing curatorial taste, and the influence of big money on what is seen in art museums today.

History of artists’ fascination with work by the self-taught

The interest of mainstream artists in work by their more isolated contemporaries began in the Nineteenth Century under the influence of Romanticism. Artists who rejected the limitations of an ossified academic tradition turned elsewhere, finding inspiration in work that was unconstrained by the artistic and social expectations of their own millieu. When Picasso said “I never drew like a child,” it was certainly rueful – an acknowledgment that even his first scribbles were made with an awareness of academic conventions and standards. In a movement described under the broader term “Primitivism,” artists turned to the work of children, tribal peoples, social isolates, mental patients and rural peasantry. The interest in this last – folk art – was associated with various nineteenth-century nationalist movements and the origin myths of several new European states, expressed in literature and music as well as the visual arts.

A notable interest by artists in some of this material was sparked by the publication in 1922 by the physician and art historian, Hans Prinzhorn of a collection of work by mental patients in Heidelburg. It was known to be of interest to Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Paul Klee, Max Ernst, the French Surrealists, Richard Lindner, and particularly Jean Dubufett. Dubufett in turn assembled his own collection of art by mental patients and other isolated artists, creating the museum Le Compagnie de l’art brut ( Dubuffet’s term for Outsider art) in Lausanne. This work by Outsiders influenced his own art and he promoted it in the U.S.,where he had a notable impact on artists in Chicago.

Integration of Outsider art in museums

The extent to which work by Outsiders has been integrated with that of their trained contemporaries or been isolated in separate museum departments or even in specialized museums has varied with time and by institution. Paintings by the customs officer turned amateur painter, Henri Rousseau, have entered the history of modern art seamlessly by now. Anyone who regularly visited the Museum of Modern Art, New York in the 60s-70s would know the work of John Kane and Morris Hirshfield, which hung beside work by canonical European modernists, with nothing to indicate that they might be considered in a separate category. That has not been the case during the past several decades when they have remained in the storerooms.

Exoticizing the lives of the artists over the work itself

Underlying the collection and exhibition of the work of Outsiders is the fact that it is made by impoverished, often politically marginalized artists or by those isolated because of mental illness, and only enters museums such as the National Gallery of Art after it has been discovered by artists, accepted by mainstream galleries and sold to the wealthy. This creates an asymmetry of money, power and agency that it is hard to ignore – and at times has reflected a romantic attitude to these artists’ deprivations. Some outsider artists created work entirely for themselves – which is not to say that they were cut off from influence of other art and imagery they gleaned from books, magazines and popular culture. Other artists created and showed their work within their own, rural communities; in many cases it was an expression of evangelical Christianity – something that most art museums have not tried to address in any serious way. A few of the artists were happy to be represented by mainstream art galleries as long ago as the 1930s. But the majority of outsider artists – the quilters of Gees Bend being notable exceptions – have entered museums without their participation and/or posthumously, with no say over how their work is presented.

This lack of participation by outsider artists in museum exhibitions of their work is in stark contrast to the participation of their trained contemporaries, whose exhibitions are sometimes installed by the artists themselves, and usually accompanied by catalogs that include interviews with the artists and essays discussing the artist’s style, development, subject matter, influences and, if not standard, the artist’s choices of how and where to present the work. That said, in the past decade monographic exhibitions of the work of Martin Ramirez, James Castle, Judith Scott and Horace Pippin have been exceptional in foregrounding their art over the artists’ biographies, a true change for the better.

A walking guide on what to see in the huge exhibition

If you want some direction through the exhibition, I’d recommend the following, not because they are the most important, but because the artists are the least published and/or the work is difficult to see because it is in private or obscure collections or needs to be stored away from light. (Note: I’m making no distinction as to the artists’ backgrounds:)

- In the entrance room see Judith Scott’s powerful, wrapped bundles;

- Room 2 has Patrick J. Sullivan’s dreamlike “The Fourth Dimension” and Seraphine Louis’ “Feuilles,” an abundance of flowers that expand into atmospheric, layered color;

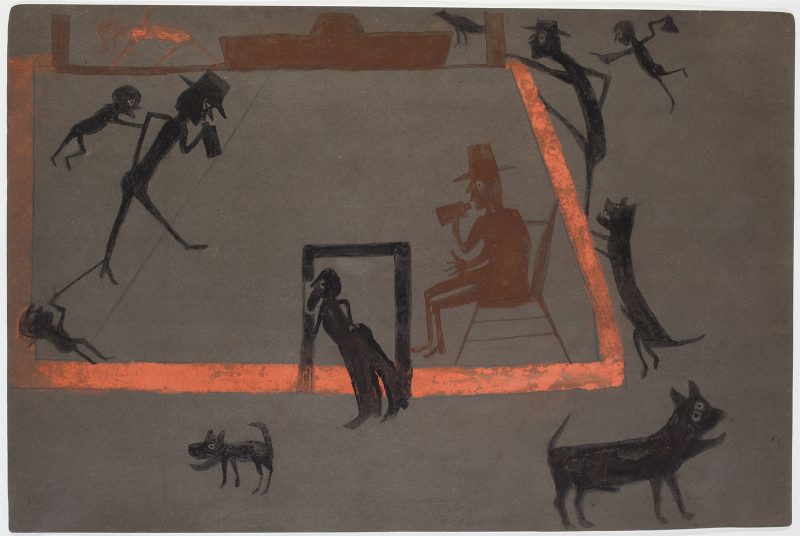

- The entirety of Room 3 is stunning, and a concentrated viewing experience could stop here; it includes a particularly sophisticated Jacob Lawrence that uses a naive language to create a formally and intellectually complex painting, as well as wonderful work by William Edmondson, John Flannagan, Janet Sobel, Bill Traylor, Morris Hirshfield and Horrace Pippin.

- Room 4 is a rare chance to see the Chicago Imagists outside of Chicago;

- In Room 5 Steve Ashby tells adult stories with disarming, child-like simplicity;

- Room 6 displays John Outterbridge and Noah Purifoy’s haunting assemblages in interesting juxtaposition to the better-known Bay Area Funk artists.

- In Room 7 stop — have a seat and watch the slide show of artists who created entire worlds, not just objects.

- Room 9 contains Forrest Bess’s personal iconography of sex and alchemy;

- Room 11 includes Zoe Leonard’s fictional archive, which begs for credence, and the work of Lee Godie who established her own celebrity from the ground up, through performance and documentation;

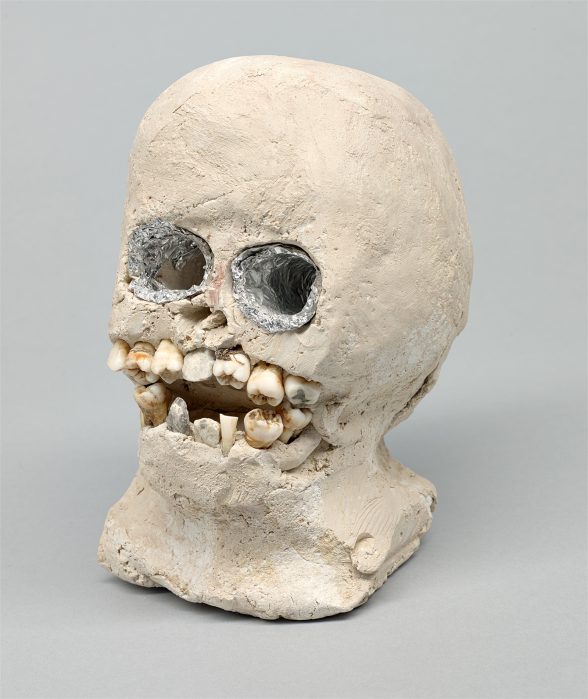

- In Room 12 are Alan Shields and Howardina Pindell, artists who have not received their due; And in the final area, Greer Lankton’s spooky dolls for grown ups are displayed along with her diaristic writings.

Parting Thought about a show this size

An exhibition this size only encourages paying limited attention to each work — which I don’t think should be the job of museums. It also undermines any point the curator might be trying to make. Given this overabundance, the best advice I have for visitors is go – and enjoy it. Look at what catches your eye, especially the unfamiliar. Don’t try to see everything or worry about what you miss. Time spent with any of the material is certain to be a rewarding experience.

“Outliers and American Vanguard,” National Gallery of Art, Washington DC to May 13, 2018. The show travels to the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, June 24–September 30, 2018 and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, November 18, 2018–March 18, 2019.