Marcel Duchamp, joker that he was, would certainly be amused at the thought that he’s the subject of an exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, of all places. And a lively and fascinating exhibition it is! At least one federal institution is taking a liberal attitude to immigration, albeit legal, as Duchamp became a naturalized citizen in 1955.

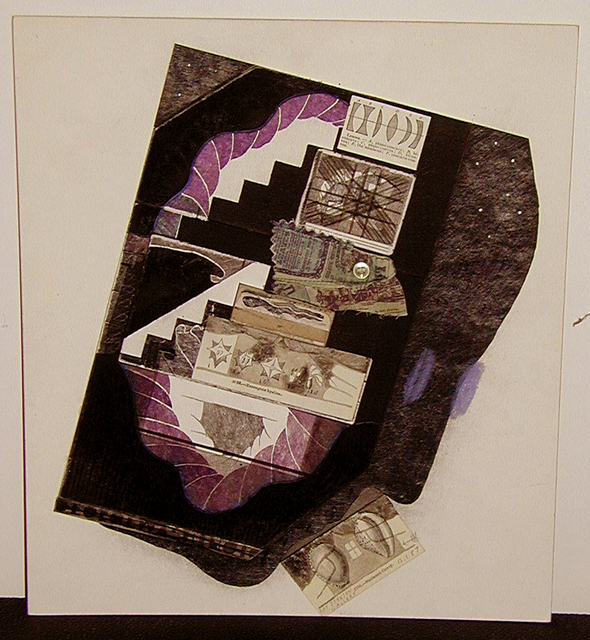

More than a hundred works include photographic portraits and self-portraits (as his everyday self and in the guise of various alter-egos) as well as abstract portraits and self-portraits representing the artist through his work and/or attributes; the later include Duchamp’s Boîte-Series D of 1961, a variation on his earlier Boîte-en-valise ( a miniature retrospective of his own work assembled for travel, in a suitcase), Mel Bochner’s alphabetic re-arrangement of a citation from Duchamp’s description of The Large Glass, Brian O’Dougherty’s portrait based on an electrocardiogram of the artist and Joseph Cornell’s account of a dream about Duchamp.

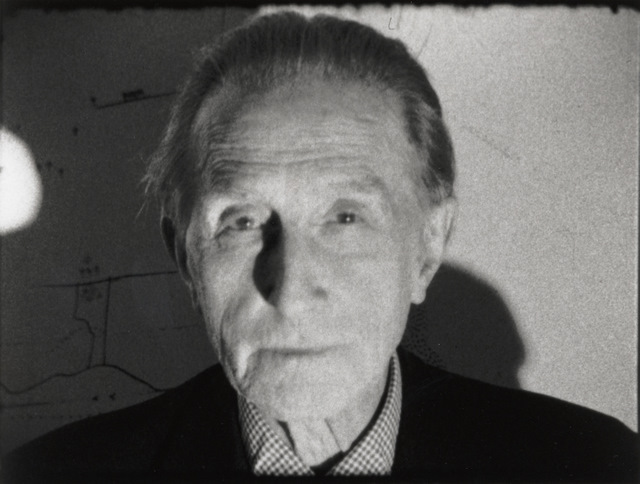

The exhibition’s curators, Anne Collins Goodyear of the Portrait Gallery and James W. McManus, professor emeritus of art history at Cal State, Chico, suggest that Duchamp’s various personae as well as the self he presented to his portraitists should be considered part of his oeuvre. They cite the critic Henry McBride (a contemporary of Duchamp’s): Marcel in real life is pure fantasy. If you were to study his paintings, and particularly his art constructions, and were to try to conjure up his physical appearance, you could not fail to guess him, for he is his own best creation,…. Goodyear writes that Duchamp deployed self-portraiture as a means to construct his future reputation, and that his most significant legacy is to demonstrate that one thing, one person, can be many things at once … identity, then … is ultimately unstable and multiple.

Duchamp was certainly not the first artist to attempt to construct his own reputation; Michaelangelo edited his biographers, Salvator Rosa was famously self-publicising, and Courbet created a series of youthful self-portraits in multiple guises that drew on Romantic ideas of self-presentation as role-playing; his image was so well-known that he became the most caricatured artist of his day. But Duchamp is certainly twentieth-century art’s most well-known self-fashioner and he captured the imagination of many successors. In addition to those already mentioned, the exhibition includes work by Alfred Stieglitz, Francis Picabia, Florine Stettheimer, Irving Penn, Frederick Kiesler, Richard Avedon, Richard Pettibone, Sturtevant, Richard Hamilton, Red Grooms, Mark Tansey, David Hammons, and Douglas Gordon, among others.

As would be expected when Duchamp is the subject, loans from the Philadelphia Museum of Art and contributions from its curators are central to the exhibition; but if you want to explore the range of portraits of Philadelphia’s local art hero you’ll have to go to D.C. by August 2, since the exhibition isn’t traveling.

A symposium held in connection with the exhibition’s opening explored Duchamp as subject and the larger question of what constituted a portrait in the early Twentieth Century. Wendy Reaves, curator at the Portrait Gallery, discussed the first two decades of the 20th century as a time when many took a theatrical attitude to self-presentation; she reviewed various abstract portraits including Virgil Thompson’s musical portraits, Marius de Zayas’ cartoons, Picabia’s abstract portraits and puppets and dolls by numerous artists. Louis Katchur, professor at Kean University, discussed the tradition of avant garde artists’ gatherings and their painted group portraits by Fantin-Latour and Maurice Denis, as well as photographs of the Futurists and others.

David Hopkins, professor at the University of Glasgow, discussed Man Ray’s photograph Dust Breeding in a manner exemplary of the hermeneutics beloved by Duchamp scholars. He managed to link the photographic detail of dust on The Large Glass with aerial photography from WWI, hence death, and Duchamp’s male and female personae with the procreation of the photograph’s title. Finally Brian O’Dougherty gave a restrained but masterly performance documenting the execution of his portrait of Duchamp. Spurred by Duchamp’s comment that art died in museums, O’Dougherty was determined to create a portrait that would somehow extend the life of its subject. O’Dougherty, who had trained as a doctor, took an electrocardiogram of Duchamp which he used to generate a portrait with a heartbeat that would function perpetually.

Accompanying the exhibition is an extremely handsome and fully-illustrated catalog, Inventing Marcel Duchamp: The Dynamics of Portraiture (MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-262-01300-0) with articles by Janine A. Metcalf, Francis M. Naumann and Michael R. Taylor, in addition to the curators. Unusually for catalogs of contemporary art, it has very useful individual entries for each of the exhibited works. The book is stylishly designed and benefits from footnotes, rather than end-notes, in the catalog section. The designer, however, had the counterproductive idea to set the actual catalog entries perpendicular to the explanatory text. This makes for beautiful page layouts but gives the reader a literal pain in the neck.