For those of you who know me, you know that I’m very loud. I’m very loud about many subjects, but I’m especially loud about being fat. Sometimes, when I’m in a room full of skinnies, I make it a point to be even louder about being fat. Be careful, or else I’ll sit on you until you suffocate and then you’ll die and never get to make art again.

This matters a lot to me in the world that I occupy. In Performanceland, we favor certain bodies over others — even suggesting that there’s more verisimilitude in a lithe body than in a heavy one. That is to say: we are more likely to believe or agree with what comes out of Ryan Gosling’s mouth than Seth Rogen’s. But the joke’s on us because they’re both equally awful people.

I’m gonna be tangential and talk about a specific visual artist’s work for a while. Bear with me theatre people, I’ll get back to you soon, I promise. Enjoy not being the center of attention for once. And the word verisimilitude is going to come up often. For clarity’s sake, I’m referring to the idea that the body you see depicted on a stage or on a canvas is the body that everyone should recognize as their own. It’s the idea that the image of the “everyman” or “protagonist” is something that can be quantified, measured, or defined.

Encountering Botero in Colombia

Back in July, I visited Colombia for the first time in over ten years and found that a lot had changed. Mid-stage capitalism was in full swing, though it seemed like Colombians had done a very good job of making it their own. There were very few McDonalds or Burger Kings to be found, but instead, far more fast food chains that served churrasco, bandejas paisas (!!!), and arepas.

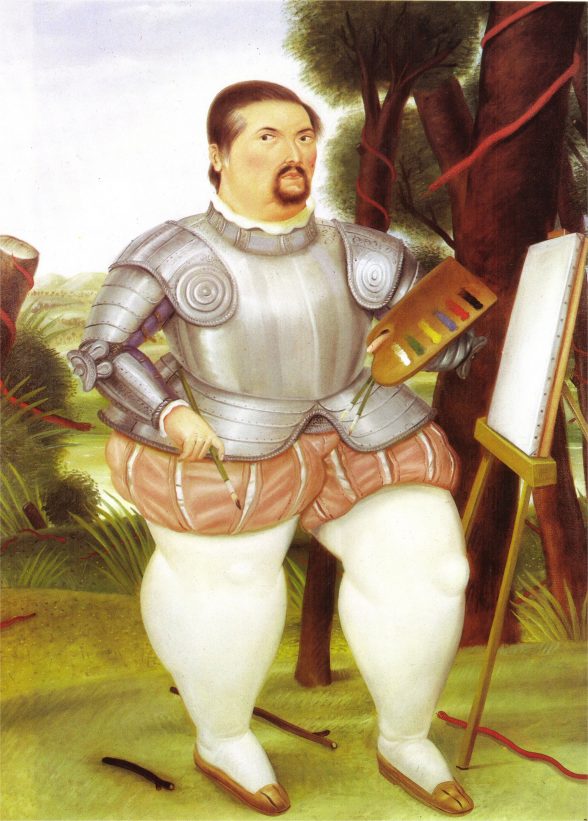

Medellín, a city several miles north of the capital, was an extension of this neoliberalism in action. What was once marked as one of the most dangerous cities in the world had become a low-key tourist destination for those with wanderlust. While I was there, I saw a lot of this guy’s work in the Museum of Antioquia:

This is Fernando Botero. He’s a lot thinner in person — the curves are actually part of his signature style. Botero’s work is comprised almost entirely of portraits just like this one: voluptuous, jubilant, and affectionately crafted. Every Botero painting is fat, juicy, and begging to be squeezed.

I spent a lot of time in the museum (with an amazing collection, by the way) ruminating on the impact of Botero’s work on the populace. For many people, Botero is seen as the quintessential Colombian artist. His statues can be found throughout Colombia, Miami, and various parts of Latin America. My mother owns two reproductions of his work, for Christ’s sake.

Here’s something else you might not know about Colombia: cosmetic surgery is huge. To say that it’s “kind of a thing” is a bit an understatement. Ironically, despite their adoration for Botero’s work, many Colombians are currently experiencing a body dysmorphia beyond compare. And I’m not speaking from a place of judgment. For some women in Colombia — especially women from low-income backgrounds — cosmetic surgery is seen as a one of the few means of escaping poverty. With a bit of work done, a career in modeling can be seen in the distance.

Undoing naturalism

Please don’t assume that the outcome of this train of thought is that Botero is part of the problem — that his work depicts fat bodies as objects of ridicule, and therefore Colombians are subconsciously avoiding said ridicule. (To be fair, the more time I spent with his work, the more I felt an inherent mockery.) But eventually I let go of that, and realized that Botero has a lot to teach us about the power of defying verisimilitude, and how a lot of our assumptions about its importance are arbitrary.

What I am saying is this: if there were more depictions of bodies like Botero’s, with the fatness of a body being less of a statement and more of a matter-of-fact, then imagine what we could learn from this art? Sculptures of Botero’s work are seen throughout Colombia. By Eurocentric beauty standards, such portraits could been seen as gaudy or kitschy, but instead they’ve transcended that judgement and his work is celebrated throughout Latin America. That his work can still be respected, with entire collections in his name in museums across the globe, is a testament to the idea that verisimilitude is a construct.

At a certain point, taking apart verisimilitude in our own art becomes about taking it apart in our society. The trumpeting of white, fit, and cis bodies as more “desirable,” or “interesting” becomes antithetical to the radical change we need in our artistic practice. The impulse to paint or sculpt what we see as reality is actually irrelevant to the current zeitgeist — finding something perpendicular to that impulse is where our culture should be going.

Back to Performanceland

Often, I find myself in the casting room hearing what a director has to say about the folks who’ve auditioned. There’s this language of who is or isn’t a “leading man” that I find incredibly irritating. And attached to it, there’s this idea that the leading man must be someone who we can “relate” to, who looks “like us,” or worse, like the person “everyone wants to be.”

With these assumptions, the director is doing two things that make me lose respect for their artistry: 1. allowing inequity to occur, and 2. searching for comfort in their decision-making. Though it’s worth noting that the casting of a fat body, a person of color, or casting against gender should not be seen as a “risk,” Botero has a lot to teach us about what can happen if we eschew our understanding of what an ideal form looks like. The rules of a Botero painting dictate that everyone is the leading man — but also the ingénue and the character actor all at once. By casting our performers against type, we tell our audience that any person can be in their shoes.

Voluptuous, curvaceous women playing Scarlett O’Hara. Luscious, thick bears playing Bond. The people who are told that they’re not right for the part? I want to see them play those parts. Aspirational casting will always be more interesting than casting within the confines of “naturalism” and verisimilitude. This is not about craft. This is about 2018, and creating a thriving ecosystem for theatre rather than allowing the medium to live in geriatrics.