Philadelphia native Jennifer Packer is having a career boom. From Tyler School of Art, to Yale, to New York City, the painter’s most recent show, Quality of Life, finds her at noted contemporary art gallery, Sikkema Jenkins & Co.. With 20 new works, Packer continues to depict the black people close to her alongside (and at times in the midst of) evanescent plantlife. In the emotional Quality of Life, Packer centers the fragile vitality of both flora and those who reside in a nation built and maintained on their oppression.

To see or not to see

The question of when visibility becomes exploitation is challenging for black artists to answer. On the one hand, you create what you love but on the other, not everyone who sees your work — and indeed not everyone who purchases your work — will lend the same affectionate eye to your content. Although not all black portraitists baulk at the consequences of visibility (Kehinde Wiley’s career relies on embracing them), Packer addresses the dilemma of exposure by obfuscating faces and settings. Visual ambiguity reminds the audience they can not consume the visages of her family and friends.

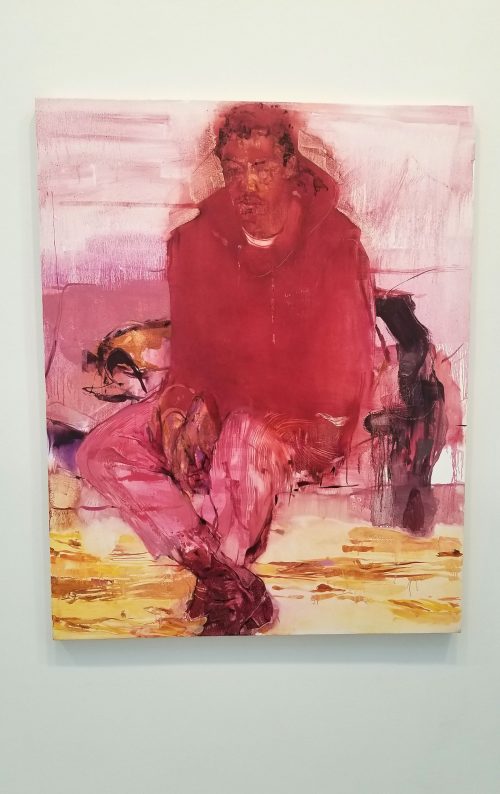

In the atrium hangs a fervent, magenta, life-sized portrait, “The Body Has Memory.” A young person casually sits on indistinguishable furniture in a room vaguely indicated by stretches of paint streaks and calligraphic strokes. With boots and a hoodie on, the subject appears to be a guest in this room. Though the face is scarcely articulated through the blush of magenta and umber, the figure appears to be looking down, uninterested the viewer’s gaze.

Addition by subtraction

The next painting, “Laquan (2),” is of equal scale and blasts a hotter pink throughout. This time, desiccated roses and fronds fan across the canvas and bend towards the floor. Packer has wiped away paint to indicate where light touches the plants and defines distant shadows with a layer of purple. The coloration is reminiscent of digital photo manipulation, similar to the flattened and inverted colors that result from an overly edited Instagram image. If the title is supposed to reference a person or just a house plant that was given a name to help it grow is not readily apparent although, four initials (W, L, M, L) are lightly placed in each corner.

These first two paintings are perhaps the boldest in the show. Across the room the medium-sized “It’s Expensive to Be Poor” is a subdued yet powerful portrait. The title is based on a James Baldwin quote. A deep blue streak shrouds the subject in darkness. Unlike the other subjects, this one confronts the viewer with crossed arms and a straight gaze. Green plantlife dangles gently to the left side, the curls of the vine matching the graceful fingers Packer makes highly visible against a translucent body. The latent queerness of the image harkens back to Baldwin’s positioning as a black gay man in America.

A trick of the eye

Some of the smaller portraits, “Eric,” “A Conversation,” “M. Heller,” while skillful, come across more as beautiful studies than fully realized paintings. The inattentiveness of the subjects and travel-friendly size make the work feel like academic assignments. “Cheyenne,” one of the larger pieces of the show, renews observational figure painting by inserting ambiguous objects beneath and, in the case of a tenacious dark rectangle, on top of the the figure. Combined with Packer’s washed out style, this painting is a great example of how spatial ambiguities can inhibit our ability to recognize objects. Although on your screen “Cheyenne” may clearly show a dog laying on top of a supine figure, I had to look at this painting for several minutes before even noticing the canine (did you notice the red boots yet?). Packer refuses to explicitly illustrate individuals so her work necessitates that the viewer look around her subjects in order to see them. Even then, clarity does not come with immediacy — but beauty will.

Jennifer Packer, “Quality of Life” is on view November 29, 2018 – January 19, 2019 at Sikkema Jenkins & Co, 530 W22nd ST, New York, NY 10011; gallery hours: Tuesday – Saturday, 10-6; telephone: 212 929 2262

More Photos