I rode a packed El to West Philly to meet young and emerging artist Patricia Renee Thomas at her 40th Street Artist-in-Residence studio. Thomas and I first met six years ago in highschool. Our first interaction: she taught me how to use a hot glue gun.

During her childhood and middle school years, Thomas was bullied, which led her mother to transfer her and her sisters from the school to Upper Darby High School — a school of approximately 4,000 students of various social and economic backgrounds. In Patricia’s words, “You could go anywhere in Upper Darby and find like, a Filipino Canadian if you wanted to. You could find your Haitian friend who lived in Brazil for two years.”

We both found a community in the Upper Darby Art Department, led by wonderful humans Elizabeth Harendza, Heidi Galassini, Ellen Flocco, and Hind Ghazzawi. Thomas especially sought out classes taught by love.Sarah Rene, a black female artist and graduate of both Tyler School of Art (BFA) and UArts (MFA).

Thomas was always more sure that she would be a visual artist than I was. When I mention this to her, she says “Oh, I was sure.” She even spent months, after graduating from Tyler School of Art, painting in her mother’s kitchen. It was a free, (somewhat) empty, space with natural light. “Everything had to be kitchen sized” she tells me. Her sense of responsibility is too great for difficulties to hinder her practice.

Painting didn’t feel like an option at all. When I entered the painting department [at Tyler School of Art] I noticed that there were no black women painters that I could think of immediately. I remember taking these art history classes and falling in love with Michelangelo, Caravaggio and getting really sad — thinking who else? What else?

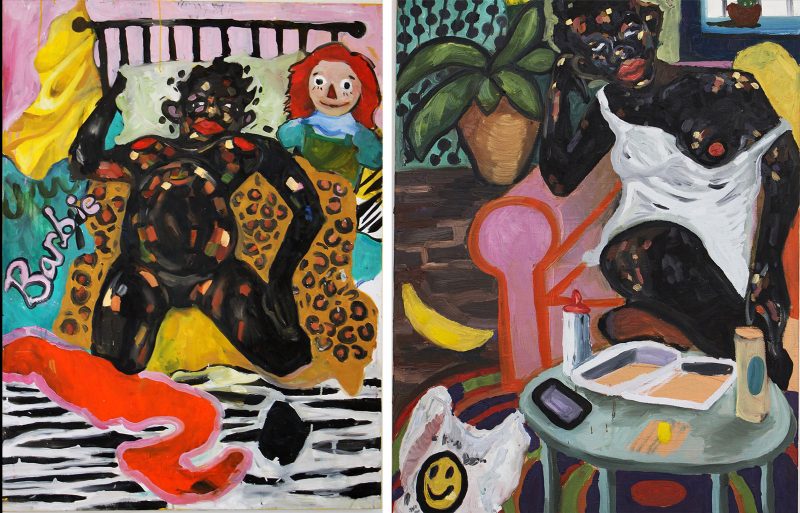

Instead of waiting for an answer, she created her own. She requested an independent study with Keith Morrison, a black, now retired painting professor at Tyler. She spent her semester painting the black figures that she rarely found in her painting classes.

After looking these figures in the eye, I thought, I can’t just hang out and paint flowers anymore. I have to make it so that black women painters who are interested in painting black people know that there is space for them. No one should have to look at your work and say, “why don’t you look at Freud?” What is Freud going to teach me? I had people literally tell me, “look at Matisse!” I don’t want to look at Matisse anymore. Show me examples of someone who is talking about what I’m talking about. After I had that realization, I just went for it. That’s what keeps me going.

Thomas paired her independent study with obsessive research into Jim Crow laws:

My parents taught me a plethora of black history, but it was usually proud black history. We were very aware of slavery, and the results of slavery, but I remember doing a very long research project on Jim Crow myself and profusely crying after. Trying to make sense of racism is really difficult if you’re not a direct victim of racism. If you grew up as a happy, black, child, you don’t really understand why anyone would hate you.

This research resulted in a new body of work that, unfortunately, was not met with open arms and minds. Thomas found that most of her peers didn’t know how to talk about her work, and many fell silent at the sight of the stark, black figures in front of them. This is when she realized that her art scared some people. They’d avoid critiquing the subject matter, saying “I really love the yellow you used in the background.”

Thomas installed her 2016/17 thesis show, “Gentrify Me, I’m a Criminal Now,” in the hallway across from where Kara Springer’s “A Small Matter of Engineering, Part II” was installed— a hallway that Tyler students walk down every day. Both she and Springer were making timely and controversial decisions, and Thomas felt, more than ever, that her paintings needed to be produced urgently. “It was election time, and many people were realizing that they had been victims of prejudice their whole lives. There’s nothing worse than that” she says.

I had never experienced so much racist activity in my life. I was called a n***** in a bar near my neighborhood, where I grew up. If I looked hard enough I could’ve probably recognized some of the people in there. And then on Temple’s campus, there was an incident where a student got hit with a brick thrown by one of the young girls in the neighborhood. I remember walking around the campus at night and seeing people cross the street…to avoid me…on campus. It happened more than once!

Thomas’s works addressed Temple students’ sense of entitlement toward and abusive treatment of the surrounding community as well as the increased incidents of overt racism following Trump’s election. The works included drawings of North Philadelphia residents and imagined paintings of black figures. “It was made for no one else but the white students in that school,” she tells me.

When the show was installed, some white classmates even confused her work with that of another black student, Jermaine Ollivierre, who happened to have writing installed elsewhere in the school. “The funniest thing about it was that [Jermaine’s work] made people SUPER uncomfortable. I was ok with that. I also wanted my show to make people uncomfortable. Either you relate to the people in the drawings, or you feel weird, and guilty, and you have to rethink your actions towards these people that you live near. They’re your neighbors.”

Apart from making poignant work, Patricia is carving out a corner of the art world and nurturing it. She’s not only creating representation for young female POC, she’s giving them the tools to excel in the arts.

I teach a class at Church of the Advocate, which was a black panther meeting hub, in Philadelphia, and is still this incredible place, with French Baroque walls that have murals of black people on them. The way you feel in there is insane. My art class is all girls, which is hilarious. We had boys but the girls kind of shunned them out of the class. They kind of expressed to me and my co-teacher, who is also a black woman, that they wanted a space for themselves. We talk all the time about black female artists. We have them make work based on black female artists. And I’m there to tell them ‘I’m a black female artist. And I work with you guys. I have a career and a job and I love what I do.’ There’s a circle that happens where they get to go home and tell their mom, ‘My teacher is a black woman, and she does it.’

Thomas teaches to ensure that the next generation of artists entering institutions of higher education is more diverse. As many of us know, art colleges tend to skew white — “because it’s riskier for POC, but also because there are fewer of us,” she says. In the future Thomas hopes to create a financial aid fund for black students in the arts.

Currently, Patricia is a resident of the 40th Street Artist-in-residence program. She also recently completed a residency at Jasper Studios. As she prepares for multiple upcoming shows, her new paintings focus on her own as well as her friends’ and family’s experiences with religion, bodies, and sexuality.

Thomas’s upcoming exhibitions include a group show opening in San Francisco on February 14, 2019 called “Forever, A Moment: Black Meditations on Time and Space”, and a solo show opening in Los Angeles on May 18 at New Image Gallery. Finally, you can see her work right here in Philadelphia in August of 2019 for the closing of her 40th Street residency (more information about dates to come!)

Interested in learning more about Kara Springer? Navigate to this podcast featuring Springer hosted by Artblog’s own Imani Roach!