Authors Preface

Hailed as the Dean of American Studio Woodworking, Wharton Esherick (1887-1970) pioneered what was once considered a utilitarian craft into a form of art. Initially trained as a painter at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), Wharton dropped out six months prior to graduation due to conflicting interests with the stylistic direction of the program. He later turned to woodworking and sculpture when his audience became more interested in his handcrafted wooden frames than his actual paintings. His distinguished wooden sculptures, avant-garde furniture creations, and woodblock prints have been exhibited at the 1940s Worlds Fair in New York, Museum of Metropolitan Art (MoMA), Renwick Gallery, Wolfsonian-FIU Museum, and Philadelphia Museum of Art. If you’re lucky, you might even come across one of his signature three-legged stools at a yard sale (just remember to look for “W.E.” carved on the bottom)!

Artist Wharton Esherick and wife Letty, an educator with an affinity for dancing, lived a bohemian lifestyle on a farm homestead, Sunekrest, in Paoli, Pennsylvania with their three young children. In 1926, Esherick borrowed money from his grandmother to build a larger dedicated studio just up the hill where he would frequently hike to watch the sunset over Valley Forge. Over the course of forty years, he masterfully evolved his studio into a home that became one of his greatest works of art. Established as the Wharton Esherick Museum in 1972, the complex consists of his original studio, a 1928 Expressionist-style garage and a 1956’s workshop designed in collaboration with renowned Philadelphia architect, Louis Kahn. Today, the museum invites us into his humble studio abode so that we too can appreciate the quintessence of Esherick and all that inspired him, most of which was right in his backyard.

Unlike the neighboring homes teetering on the crest of Valley Forge Mountain, Esherick integrated organic design principles from architect Frank Lloyd Wright, nestling his Pennsylvania barn-inspired studio into the wooded hillside. A natural building palette of stone and wood further camouflage the structure within its context. In 1966, he complemented the hobbit-like barn with a whimsical silo, adorned with a hand-painted hallucinogenic fresco of fall foliage.

I enter the museum through the former studio, a lofty jungle-like room filled with relics of his work. Tall and slender wooden sculptures rise from the floor like trees in a forest, ceramic monkeys hang from the rafter, abstract wooden ponies graze the studio, and an intricately-carved flock of birds take flight across wooden doors. Despite the tranquility of the room, there is embodied movement in the fluid forms of his work, attributed to Letty’s influence as a dancer. Esherick often joined his family at the Ruth Doing Camp for Rhythmics (dance camp) in the Adirondacks every summer and would provide woodblock illustrations for the brochures, in addition to various artistic explorations inspired by the dancers.

“You can’t get a feel for Wharton’s work without touching it. You have to touch it!” insists the docent who is stationed in Esherick’s bedroom. . And she is right. The table is covered in multiple layers of oiled finish, including the occasional layer of salad dressing that was known to spill from Esherick’s plate and get cheekily massaged into the wood grain. There is an intrinsic momentum guiding my hand over the perimeter of curved and tapered surfaces, as if I too have become a dancer in the inherent choreography of his work. From boomerang-like curved benches to kidney-shaped bread board tables, there are no square corners or straight lines in his work, just as they are non-existent in nature.

A precarious and skeletal-looking spiral stair leads to Esherick’s bedroom, where he would spend the summers while his family was away and where he would later take up permanent residence after he and Letty separated in 1938. The cozy space is fitted with built-in shelving lined with books, tiny models of his designs (known as maquettes), painted portraits, and photographs of family and friends. The most intriguing feature is the Expressionist-inspired gabled ceiling with gingerbread-like fiberboard panels** sandwiched between contorted wooden beams. The discordant geometry looming above feels foreign to his renowned organic style, as if it were a storm cloud waiting to pass. The docent explains that Esherick’s design was inspired by the wry scene imagery and shadow patterns in the silent monochromatic German film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, a rather impressive interpretation. She opens a built-in storage drawer below the bed, exposing his collection of neatly folded flannel and plaid shirts.

There is a cacophony coming from the creaky floor boards as visitors enter and exit the tiny space leading into the 1947-addition featuring the kitchen and bathroom with modern plumbing, which Esherick built after reportedly living without for over forty years (rumor has it, he lived on a cowboy diet of steak and beans, cooked over an open fire outside). Displayed on the walls of the tiny kitchen are various hand-carved wooden utensils along with colorful glazed pottery crafted by fellow artists.

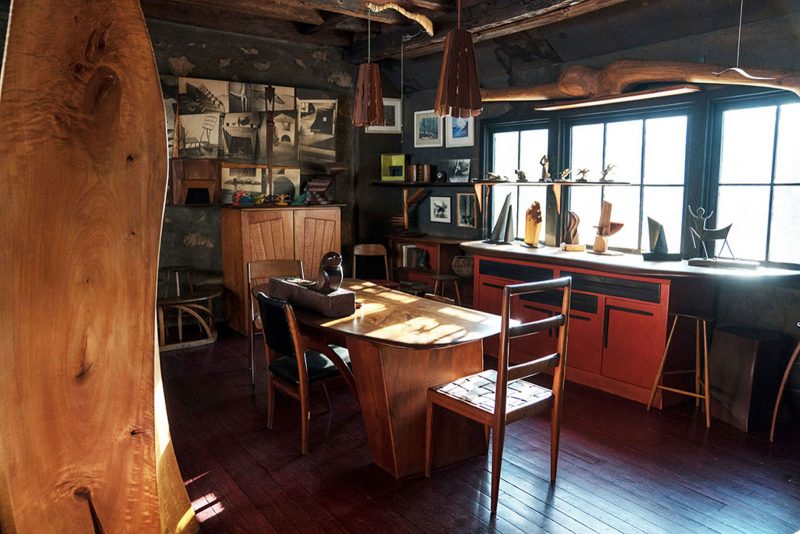

To one side sits an empty coffee table with a framed view overlooking the wilderness of Valley Forge. This was apparently Esherick’s favorite spot in the house and it’s easy to see why when the late afternoon sun warms the sinewy wooden floor, sourced from local apple and walnut tree scraps given to Esherick by a friend. The walls are clad in cherry wood, from a beloved Cherry tree that died at the time the addition was constructed. Esherick fashioned the wooden ceiling boards in an overlapping shiplap** pattern, reminiscent of his fond days spent sailing. Every element in the space has been thoughtfully designed, from the wooden countertop surrounding the sink to what can arguably be deemed the world’s most intricately carved heat vent cover.

The Wharton Esherick Museum provides a breadth of information on his life and work but more so, it offers an intimate opportunity for visitors to connect with Esherick and to experience his work on a personal level. Engrained on every piece of wood, in every nook and cranny, is an integral part of Esherick’s story as a resilient and visionary artist who persisted to live a meaningful and humble life through his creations. For that, I would certainly recommend a visit to this inspirational museum – right in Philadelphia’s backyard.

The Wharton Esherick Museum is located at 1520 Horse Shoe Trail, Malvern, PA 19355. The Museum is open by reservation only. Closed to visitors the months of January and February, the museum reopens to the public on March 4th, featuring paintings by Becky Suss (running until March 31st).

Read Mandy’s review of Becky Suss’s Esherick inspired paintings, on display recently at Fleisher-Ollman Gallery)

The museum is hosting its 26th annual design competition; this year’s theme is lighting. For more information see here.

Footnotes

** Gingerbread-like fiberboard panels: Manufactured as Celotex, this natural looking material made of sugarcane fiber was popular as an economical building material in the 1920s.

** Shiplap: Style of wooden siding that was originally used to construct the hull of a ship, where wooden boards were overlapped to create a watertight seal.

More Photos