In the October of 2020, Jasper Johns will receive a career retrospective that will span two cities; his work will be shown here in Philadelphia at The Philadelphia Museum of Art and, simultaneously, at The Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. This seems appropriate, perhaps even necessary, for an artist who has been actively showing for over sixty years, and has produced field-altering work in painting, printmaking, drawing, sculpture, and design for performance, and whose art has consistently worked a sly relationship to institutions and art history. These twin exhibitions, coming on the heels of the publication of a series of catalogues raisonné, and just in advance of the artist’s 90th birthday, will surely be occasions of much grand summing up and salute, reflecting on the significance of what is unquestionably one of the great creative careers of our lifetimes.

But Johns’s work has always seemed to me to ask more for a careful, quiet, and concentrated viewing, so I was glad to be able to see the show of his recent work at the Matthew Marks Gallery in Chelsea, where it’s on view through April 6.

Training the Eye

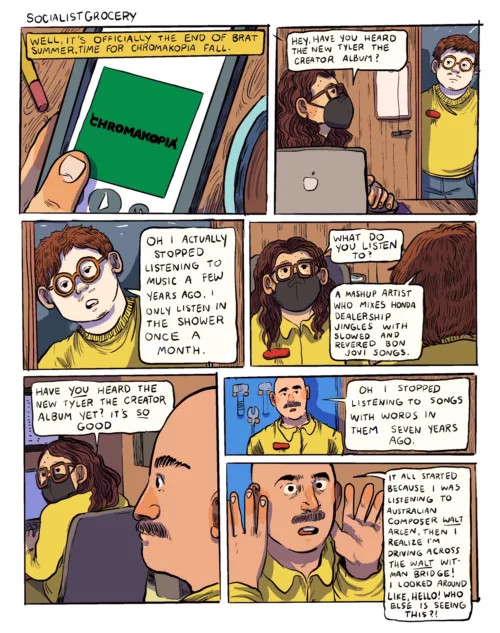

It has always been a mistake to say that anything in Jasper Johns’ work means something and yet, before the gallery door has shut behind me, I cannot help but begin to tell myself stories about the first canvas I am seeing. Tantalizing shapes seem to refer to parts of a face, to refer to the work of other artists, and to suggest other objects and symbols, as if the painting itself is begging for these shards of narrative, just as fully as it resists confirming any of them as true.

Shapes float in a creamy electric blue, a sea or a sky. Lips (or a tent) at the bottom, a ruler (nose), center. Askew or adrift an upside down Dali moustache. Two orange Os (remnants of a sign?) form portals on a pair of Philip Guston-ish observatories with spermy rays of perception beaming at them. Each (eye) portal opens onto its own black sky vista; to the right, an upside-down springtime Big Dipper dumps constellation stickmen into its night. (Equipped with paintbrushes, these three night watchmen recur in many works in the show.) The portal on the left spies a pinwheel galaxy, but just as one’s eye begins to register it in deep space, we see that it’s a (trompe l’eoile) poster, pasted to the surface. An illusion of infinite depth is replaced with the illusion of absolute flatness, which is not the same as the actual flatness of the canvas.

And the painting’s surface is as much the matter as any plays at reference Johns is making. Its exultation of diverse visual languages makes the picture that makes its subject, looking, its object and its means. Johns trains our eye to the heavens, to the body, to the pleasures, legends and technologies of seeing, and to the face he raised us to expect to see and to our own bemused befuddlement when, finally, we don’t. A beautiful blue visual and conceptual puzzle, it’s the perfect opening to the show.

Breakdowns

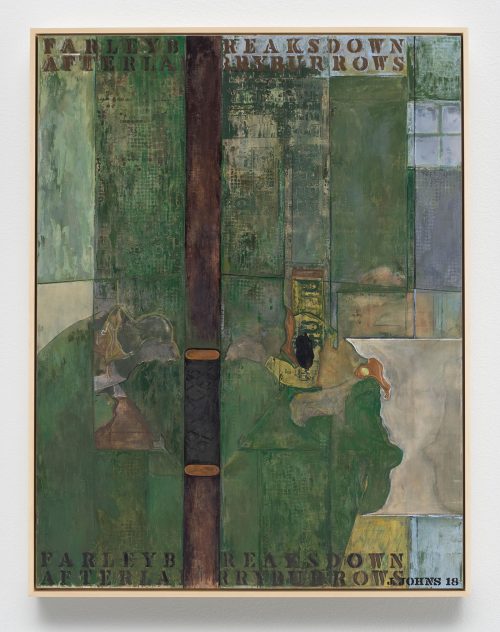

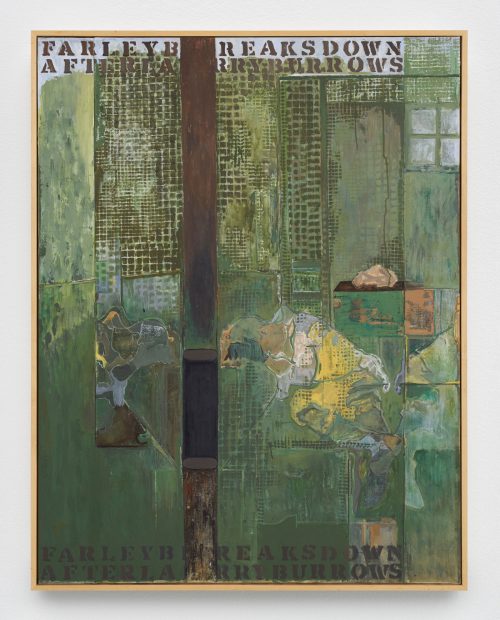

The centerpiece of this show are works derived from a photograph taken in March of 1965. When Johns was busy painting flags and targets in New York and rocking the art world establishment, war photographer Larry Burrows was three years into a mission to document the Vietnam war (he was ultimately killed, shot down over Laos in 1971, after nine years of shooting the war). On this March day, he rode along on what might have been a routine mission by a cluster of US helicopters to transport some Vietnamese infantrymen to combat. The mission went badly; after an ambush, 21 year old soldier James Farley was forced to abandon one wounded comrade on the battlefield, had his M-60 jam as his helicopter tried to escape, and collapsed in tears as he watched one of his crew mates die of multiple gunshots on the trip back to base. Life Magazine published a series of Burrows’ photos from this day and Johns has selected an image of Farley alone in his barracks, collapsed with his face in his hands, made his own image based on it, which he breaks down in to a series of searching analyses.

This may be the most wrenching emotional and the most unambiguously political material that Johns has ever dealt with. He has been famous for selecting subject matter (flags, targets, cross-hatching) that is militantly neutral. Here he takes up a famous image of an infamous time, perhaps the most shameful and divisive time in the 20th century. And the famous Burrows image, of a boy really, broken up over the deaths of his comrade, of the failure of his weapon, and his own sense of having abandoned a wounded fellow soldier to certain death on the battlefield, brought home the agony of the war to Americans in 1965.

But a half-century later, Johns is not interested in communicating the emotion of Farley’s “breakdown” or in making a statement about that war. Rather, in two canvases that center this show, he paints not so much a history painting, but an analytical painting of forgetting and an elegy of faded memory.

The abject agony of that moment Burrows documented in 1965 has disintegrated, has broken down, been reflected onto itself until the “real” image is unknown.

These paintings are the opposite of memorials; they give testimony to the experience of what is forgotten, what is only dimly (and perhaps wrongly) recollected through the screens and distortions of time. We scour the canvas for the event that Johns’ familiar stenciled letters tell us is there: “Farley Breaks Down After Larry Burrows.” The canvas is almost in camouflage; Johns’ textured patches of army drab work with purples and greys to flatten the surface, creating what look like a set of screens, obscuring the figures. The artist has broken down the visual material contained in the photo into shapes and textures and topography, each one rendered by Johns with affection for his own precision and with deep curiosity for the technical processes of creating his pictures.

Eventually, we locate Farley, note the area defined as his hands, covering his face, his ears are described by a line marking his hairline. If we look closely, we can see some “real elements of the scene” (military lockers and hardware), intermingled with the recognizably unreal (one of Johns’ ubiquitous urns, carving facing portraits from negative space, perhaps the photographer Burrows glimpsing himself, in Johns’ imagination), and some wholly mysterious shapes, almost like pieces of meat that have dropped from the sky.

In the larger painting, much here is decorated with screened imagery: cartoons, newsprint, and currency. The piece becomes an exercise in studied distance, screening and rescreening the document of specific sadness, as a quieter but more pervasive moroseness seeps into our consciousness. And in other work in the show, chiefly a series of ink on plastic drawings, Johns breaks down his Breakdowns still further. The surfaces represented are smaller, their constituent topographies rendered in simple lines on milky plastic. And the ink runs like tears, the result being a sad, streaked surface with the cold effect of analytical cubism: the relentlessness of the searching mind obsessively retouching its images of what is no longer really remembered at all.

Jasper Johns: Recent Paintings and Works on Paper, The Matthew Marks Gallery 522 W. 22nd St., New York, NY. Through April 6, 2019.