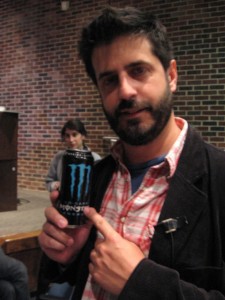

Photographer Alec Soth–the man who personally redefined Minneapolis as an art mecca, came to Penn April 22 to talk about what he does.

If you were looking at art in 2004, you may have seen Soth in a Whitney Biennial or Sao Paolo Biennial, or last year, you could have seen three of his photos–Daniel, Charles and Misty–at the Margulies Collection exhibit at Penn.

“He’s a total rock star,” said Penn’s Director of Graduate Photography Gabe Martinez in his introduction to Soth’s talk.

I may have given the wrong impression in my previous post of what Soth, who shows at Gagosian, is like; here’s my correction: He’s not in the least grumpy. He’s funny. And he loves William Eggleston. He mentioned others, including Robert Frank, but Eggleston was the biggy.

With 4 million photos a day uploaded to Flickr, and with ubiquitous cell phone photos capturing news, he wondered about whether it is possible to make meaningful photographs. “Now so many of the key images are amateur snapshots,” said Soth. “…How can you compete?”

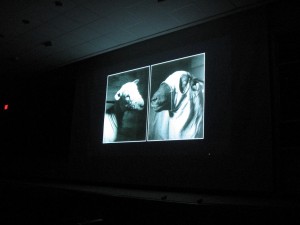

“The only answer, The Narrative Machete,” he intoned, flashing the words up on the screen displaying his Power Point slide show. Soth is interested in making a series of photos tell a story without using words. He suggested that the slide show is a neglected form that might have potential for him (I should mention that the night before he had dinner with slide show queen Zoe Strauss, among others), but the photo book is his chief output and his chief solution to the problem.

Here are the names of some of his books (here they are on Amazon):

The Last Days of W (really a newspaper)

Fashion Magazine

NIAGARA

Sleeping by the Mississippi

Dog Days, Bogotá

Soth was inspired to take his first photography road trip after hearing photographer Joel Sternfeld lecture at his college. “The idea of the road trip, I could do that, I could drive around and that could be my life.” So on a spring break, he drove from Minneapolis to Memphis. He also has spent a fair amount of time photographing people in bars.

Being in Minnesota off the beaten art track gave him a big advantage. “I was free to try things, show them, and it doesn’t matter,” he said. From an early show of photos of sheep, police, military, and a sleep clinic, he learned two lessons–accessibility and the need for free association, with one picture leading to the next one. “The works lacked accessibility except for the sheep.”

Soth is a natural teller of stories. Here’s one he told about Bonnie, one of the photo subjects in Sleeping by the Mississippi:

Bonnie is the wife of a Pentecostal minister, whom she drowns out. She had an “Eggleston-ish” picture on her wall that Soth admired. She saw his interest, put the picture on the table, and then kept pushing the picture toward him bit by bit. “I’m trying to get something from her, a picture, and she’s grying to get something from me–my soul,” he said.

It’s the exchange between him and his subjects that interests him. Someone who took a video of Soth approaching and photographing strangers called him a used car salesman of a photographer (gosh, this reminds me of Kehinde Wiley convincing young men to pose for him). Soth mostly uses a large format 8×10 camera, so he’s adjusting while the subject is waiting and waiting, “and they kind of stop thinking about how they look. I don’t claim to know anything about these people. It’s like a bird. I swoop in and grab the fish.”

Talking about his book NIAGARA, he said, “I wanted to use place again as a metaphor, but for different issues–love and romance.”

He also found despair and destruction. The wall of water’s appeal is partly that it’s destructive he said. “New love is destructive. It’s like a Roy Orbison song, building to a crescendo.”

The Niagara photos that he showed, including some nude photos of couples, are not exactly romantic even though they are about love.

“In Mississipi, I never got turned down (by potential subjects); in Niagara I was constantly turned down.”

After taking on assignments and commissions, he joined Magnum Photos. At his first Magnum get together another photographer walked up to him and hissed, “‘You’re using people.'” The comment got to him. He says some of the photos are problematic.

The life of photographing on assignment also taught him something about what’s important to his work:

“I really learned that I’m not interested in photographing celebrities at all. that whole exchange thing I’m looking for doesn’t happen with them.”

He gave some pretty interesting answers during the Q&A–

About sacrificing his family life when he’s on the road:

“I don’t bring them [his wife and daughter] in the car. I don’t like photographing my family. I really feed off the separation.

“I hate photography and I’m ruining my family.”

About his frustration with photography as a medium:

“The reason I do photography is it’s really fun, moving around and in the world–and at this point, I’m really good at it.”

About working with the large format camera:

“It’s not that heavy. When I did that Fashion Magazine work, it was all done with the 8 x 10 camera. I got really fast with it. I’m open to work in different ways. I want to think like a filmmaker. I don’t want to have a look. I don’t want to photograph sheep the rest of my life.”

About the houseboat on ice:

“I was never the bohemian guy living on the road. I had a regular job. I just pretended. Then I met these people who did live that life.”

About text and pictures:

“Text with images doesn’t work. It usually kills the picture.”

About setting up shots and poses:

“It’s like your family pictures. I usually don’t tell people to place your arm here. I have no problem telling people to move. I never claimed being a documentary photographer.”

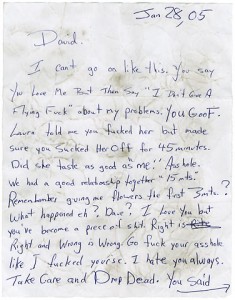

About the source of a devastating letter he showed from NIAGARA:

“The letter was given to me. …Niagara attracts suicides, too. There’s a job there of pulling bodies out of the falls. None of the letters was fabricated.”

About using people:

“I’m deeply conflicted. I’m in the midst of a bad experience. I’m hoping I won’t get sued. And she’s underage. I’m just not proud of it. As crimes go, it’s not the worst.”

About connecting to and selecting subjects:

“I’m a believer in chemistry.”